Quintuple Simultaneous Booster Landings with kOS

Here’s a video of the full mission

Here’s a fun video from testing

X link if you have comments: here.

Read the code here.

I have a tendency to only write blog posts about things I think are impressive. This blog post isn’t very technically impressive to me, but documenting your work has value in and of itself. Mischa Johal, THE UBC SOLAR WIZARD, has done a great job at drilling into our heads at UBC Solar the importance of documentation.

I was going to make this blog post understandable to non-technical non-kOS folk and hence increase the readership infinitely, however I realized I’m the only person who will ever read this.

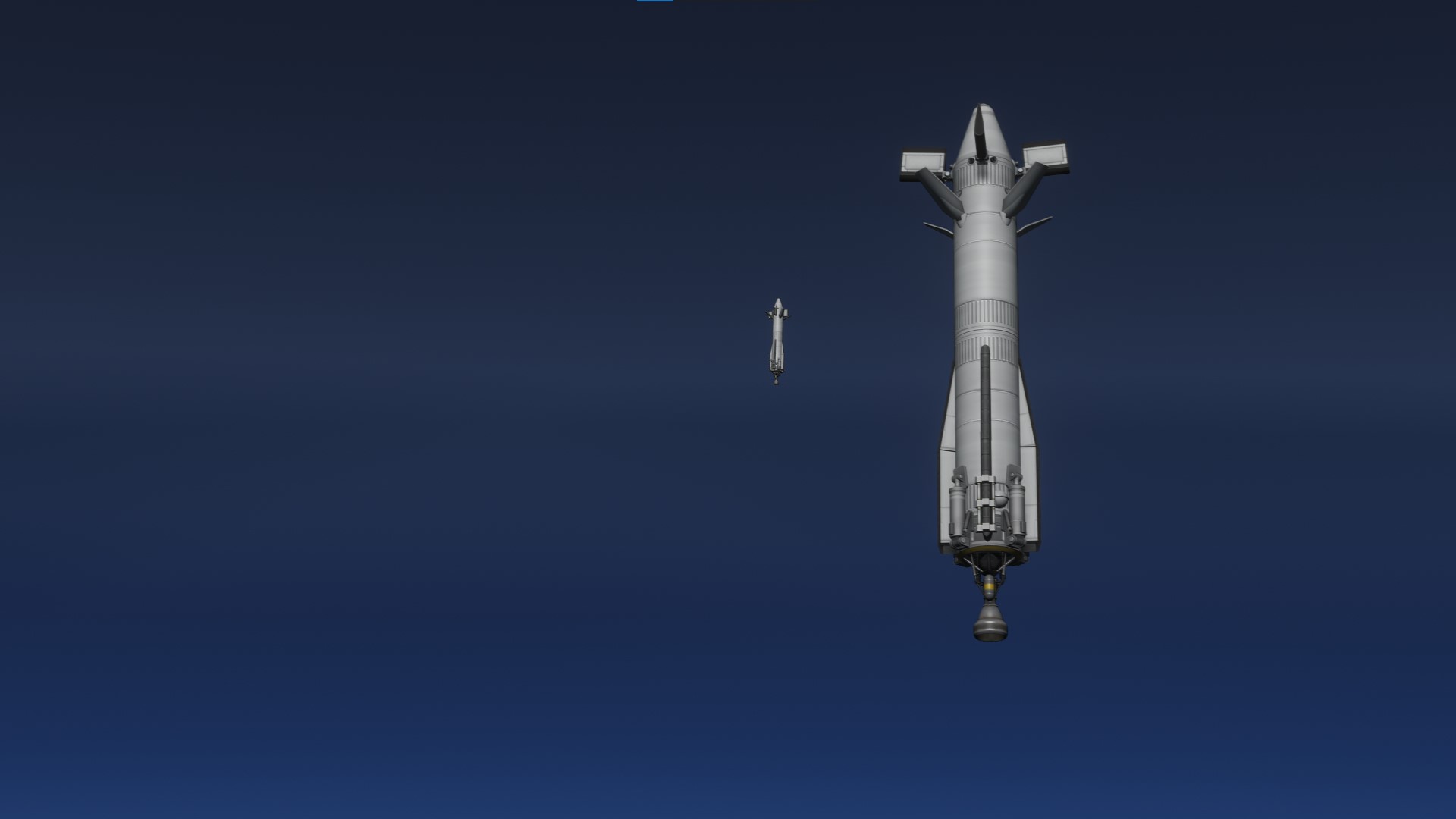

This blog post is a continuation of my previous post on How to Land an Orbital Rocket Booster with kOS. In that post I described how I figured out how to write the fundamental code required to land a booster. Since then, I tinkered some more to create a fully autonomous KSP launch vehicle that can land 5 boosters simultaneously. It is completely beautiful and magical to watch agents you wrote autonomously navigate an environment - agents that are self landing rockets!!

kOS is still a shitty language

In my previous blog post I went on and on about why kOS is a shitty language. This remains true. The unique nature of this language makes it not very applicable to other projects. This has made me hesitant about continuing any projects with kOS as they aren’t very technically informative. However, rockets landing is magical. Since the previous blog post I found out there is a KSP mod for controlling rockets with Python. Rewriting the code with kRPC again falls into the category of a project that isn’t very technologically insightful. Let’s see if the lord gives me enough strength to work on firmware instead of KSP for the foreseeable future.

This is all to say that this isn’t a technologically insightful or impressive project. There will be no impressive code, algorithms, or flight mechanics in this blog post. Just fucking around with a shitty language to get boosters to land. Interspersed with some remarkable pictures - Romans could have never imaged this!

Beauty is the Purpose

On real launch vehicles, getting the payload into orbit is the most important objective of every launch, recovery of hardware is secondary. However, unlike a real satellite, the output of my scripts is not economically productive. The output of my scripts is purely watching boosters autonomously land and marvelling at the sight. This is important context for understanding the parameters for state changes during launch (mass instead of velocity).

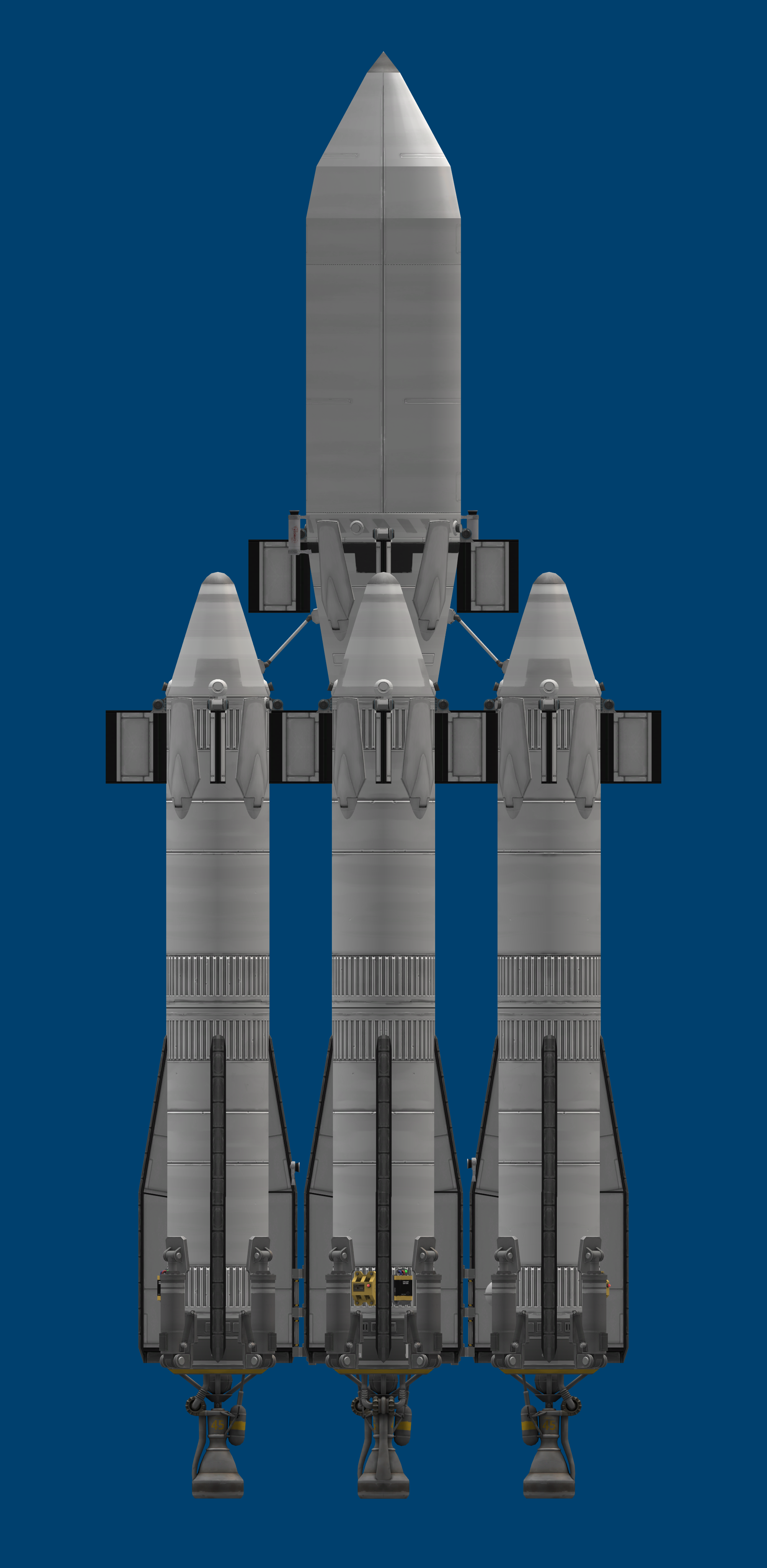

The Dzhanibekov (most impressive Cosmonaut to ever live who went on crazy Salyut repair missions) launch vehicle is a design that have a single core with 4 side mounted boosters. It has a payload capacity of about 1 ton in KSP. This is an extremely overengineered rocket because it’s goal is to look cool, not be efficient. One productive insight from this project is a better appreciation of the difficulty of recovering high-energy stages. The side boosters separate at around 700/s and ~28km altitude. This is close enough to the launch site that the boostback burn is not very expensive. However, the center core separates at a far higher altitude and higher velocity, meaning it requires far more fuel to return to the launch site. This is sub-optimal as you are leaving a lot of payload capacity on the table. Hence why SpaceX doesn’t try to recover the center core of the Falcon Heavy anymore.

How Ascent Works

Every stage on the rocket has it’s own script and the center core controls the ascent. The center core script lerps between the initial pitch and the final pitch at the 25km, which is 45 degrees from vertical. These values were determined from my experience in KSP and flight testing. Also, note that I had to write the LERP function manually as kOS doesn’t have it built it. Below is part of the function in the KOS-Scripts/Dzhanibekov/Dzhanibekov-Core.ks file. Like I said, no beautiful code in sight.

UNTIL SHIP:ALTITUDE > 30000 {

SET targetBearing to 90.

SET targetPitch to LERP(90, 45, CLAMP(SHIP:ALTITUDE, 0, 25000)/25000).

SET targetRoll to LERP(-90, 0, CLAMP(SHIP:ALTITUDE, 0, 2000)/2000).

LOCK STEERING TO HEADING(targetBearing, targetPitch, targetRoll).

}

Like all orbital rockets, we want to achieve a horizontal velocity of ~2200m/s to stay in orbit around Kerbin. However, we also need to return the boosters to the launch site. Because the boosters have to do boostback burns to arrest their horizontal velocity and move their impact location from far in the ocean to back at the same centre, we want to have as little horizontal velocity as is reasonable when we separate the boosters. That’s why we use a lofted trajectory to get to orbit. For reference, as Matt Lowne explains in this video that taught me how to get into orbit in KSP years ago, on a standard ascent profile you aim for 45 degrees off vertical when you’re at 10km. We aim for 45 degrees off vertical at 25km. This decreases the fuel required for the boostback burn and hence increases payload performance.

How Staging Works

The upper stage and boosters are dorment until their respective staging events. They wake up when particular mass values are reached. The core for this is shown below. Note that the UNTIL loop is just the opposite of a while loop. It runs the code until the condition is true.

Center Core Script:

IF (SHIP:MASS < 35.5 and SHIP:STAGENUM >= initialStageNum - 1) {

LOCK STEERING TO srfPrograde.

WAIT 2.5.

STAGE.

LOCK STEERING TO HEADING(targetBearing, targetPitch, -90).

WAIT 0.5.

}

Booster Script:

PRINT "WAITING FOR STAGING" at (0, 0).

UNTIL SHIP:MASS < 35.5 {}

WAIT 2.6.

Print "STAGED " at (0, 0).

LOCK THROTTLE TO 0.

The messaging system between separate scripts in kOS is slightly complicated, so I decided it was easier for each script to watch for staging events on their own instead of a central script telling all the others to wake up.

I tried to make each script detect staging events on their own, but this failed. The number of stages on a vehicle in kOS can be read with “SHIP:STAGENUM”. However, the number of stages on a vehicle only updates when the player is currently looking at a vehicle. This is a limitation of kOS as it has to work around KSP, which is designed for a single craft to be controlled at a time. This is why I had to use the “SHIP:MASS” value to detect staging events. The center core and boosters all detect the criteria for staging (Criteria: total rocket mass < 35.5t) individually and then move onto the next mission state themselves.

Batshit Crazy Boostback Burn Startup

The atmosphere of Kerbin is not balanced as well at God balanced Earth’s atmosphere. When we stage the boosters, we are still only 28km above the surface of Kerbin. This means aerodynamic affects play a major role in the control of the boosters. Unlike Falcon 9’s comparatively calm reorientation for boostback where it is above the atmosphere, our boosters are still in the atmosphere and have to fight against it. We can’t rely purely on RCS to reorient the boosters and atmospheric forces are too strong. So, we fire the engines once we are within 90 degree of the boostback burn direction vector. This leads to a batshit crazy looking separation and boostback startup as all the boosters are point in different directions and getting wildly flung around by the atmosphere. Watch the video at the top at the 1:51 mark to see what I mean.

Also, in testing I had the force of the decouple between the center core and the boosters set too high. Because the decoupler is at the bottom of the boosters for aesthetic reasons, this meant the top of the boosters would be pushed into the center core as the bottom was pushed away. Soyuz Style - This image really gets the point across. The solution was the decrease the force the decouplers exerted and to add small solid separation motors. Note that the force vector of the separation motors runs through the center of mass of the boosters to ensure no torque.

“Realistic” Upper Stage Burn

Once the center core propels the stack to an apogee of 77 km (exterimentally found to be the optimal value to have enough fuel to land), the second stage separates and continues onto orbit.

When you’re playing KSP yourself, the common way to get the second stage into orbit is to create a maneuver node at the apoapsis and burn prograde until you have your desired periapsis (likely above 70km, the barrier of the atmosphere). However, this usually leads to a coast phase between separation of the first stage and startup of the second stage engine. This is not very realistic, so I wanted to avoid it.

Instead, I start the second stage engine immediately at a throttle of 50%. The engine keeps running until we make orbit. This makes a far more realistic looking ascent profile.

An issue emerges when the engine is ran at a throttle greater than ~50%. Because the second stage starts it’s burn so early, it is still increasing in altitude and is far away from it’s peak on it’s parabolic flight, the apoapsis. This means that as we coast to apoapsis, the thrust from the engine is making that point higher and higher and further away in time. If this flight profile is followed, we keep burning to increase our apoapsis, but never efficiently enough to increase our periapsis so we reach a stable orbit (Oberth effect ftw).

To solve this, I have the second stage engine throttle down to 50% and control it’s pitch to ensure the apoapsis doesn’t run away from us. When we point down, the apoapsis decreases in height and comes closer to us in time. The opposite is true when we point up. So, the upper stage script is constantly adjusting the pitch to keep the apoapsis at a constant time away from us. It estimates the remaining time in the burn, and tries to make it so that we reach the apoapsis right when the burn ends. Once you understand the formulas, the math for this is very simple to implement.

CLEARSCREEN.

Print "BURNING TO ORBIT" at (0, 0).

LOCK STEERING to HEADING(targetBearing, 10, 0).

LOCK THROTTLE to 0.5.

UNTIL SHIP:ALTITUDE > 65000 { PRINT "WAITING FOR 65KM ALTITUDE FOR FINE CONTROL" at (0, 0).}

// We aim to burn until 10 seconds after the apoapsis to get into orbit, so calculate throttle based off this target burn time

UNTIL ORBIT:PERIAPSIS > 75000 {

SET shipdV to 9.81 * isp * ln(SHIP:MASS / SHIP:DRYMASS).

SET remainingdVToLEO to leoVel - SHIP:VELOCITY:ORBIT:MAG.

SET finalWetMass to SHIP:DRYMASS * 2.71828^(remainingdVToLEO / (9.81 * isp)).

SET burnMass to SHIP:MASS - finalWetMass.

SET burnTime to burnMass / massFlowRate.

SET targetApTime to 10. // We want to be 10 seconds away from apoapsis forever

SET timeToAp to ETA:APOAPSIS.

SET targetPitch to CLAMP((targetApTime - timeToAp)*0.5, -30, 30).

LOCK STEERING to HEADING(targetBearing, targetPitch, 0).

PrintValue("Engine ISP", isp, 2).

PrintValue("Engine Mass Flow Rate (t)", massFlowRate, 3).

// The rest of the print statements are not included

}

Booster Aerodynamic Control Issues

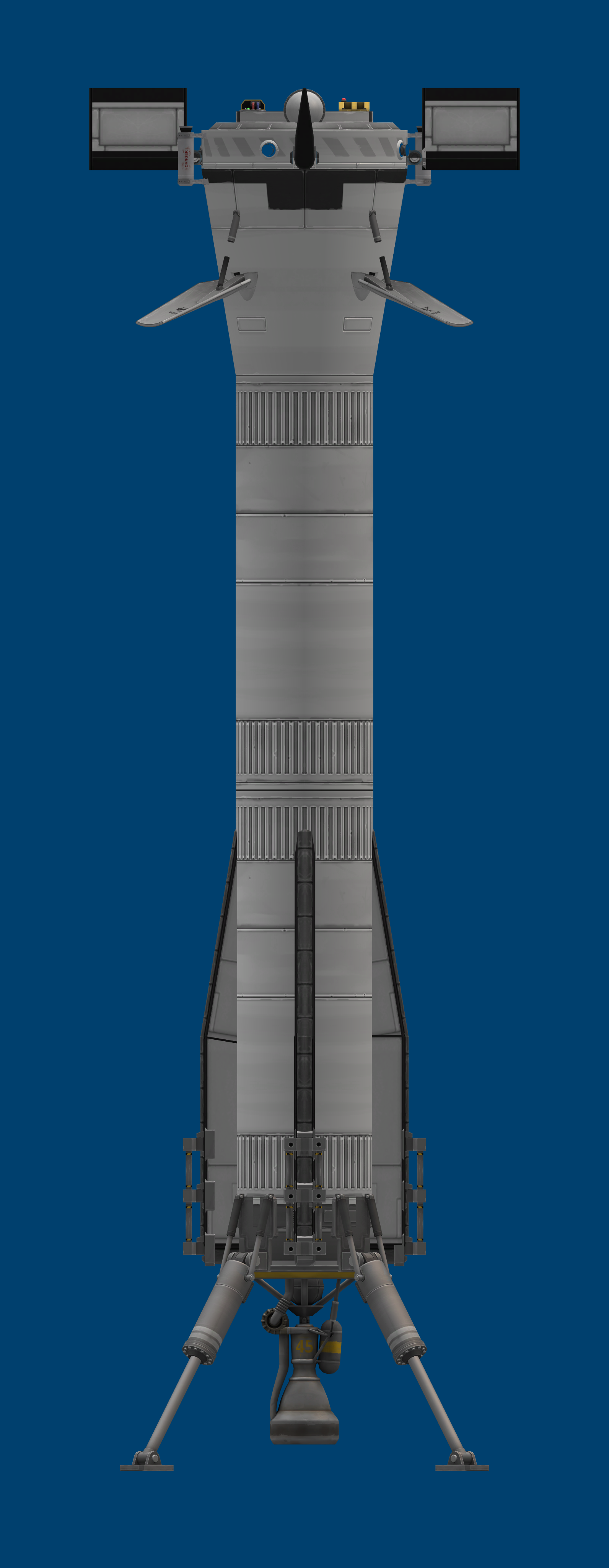

When I was first testing the landing script, I only needed to test descent and not worry about ascent. This meant I only had to optimize for aerodynamics on descent. If you don’t understand how to optimize a booster for descent I’m not gonna be able to explain it without being with you in person - If you’d like this please send me a dm. The basic principles are that you want high drag and for your center of mass to be below your center of drag. However, on ascent you want the opposite. The Falcon 9 solves this with deployable grid fins, but we don’t have this in KSP 1 (RIP KSP 2).

Because your rocket burns fuel as it ascends, the center of mass shifts. We can set the rocket to first use fuel from the upper fuel tanks so that the COM shifts downwards. In a scenerio where our COL (Center of Lift) stays constant (Eg. New Glenn without deployable aero surfaces), at the begining of our first stage burn we could have COM below COL to ensure we fly point end up, and at the end when we’re flying back, we could have COM above COL to ensure we fly engines first. In my first iteration of the vehicle this was what I aimed for with New Glenn / Superheavy chines at the bottom of the booster and non-deployable fins at the top, Howeverm the center of mass didn’t shift enough to allow for stable ascent and stable descent.

The solution (as SpaceX learned on Falcon 9!) is deployable control surfaces. Instead of having static fins, I added joints from the Breaking Ground DLC to the fins so they could be stowed on ascent and deployed for descent. This solves to COL problem as we can artificially shift it when we descent by deploying fins at the top of the rocket.

Another issue was the drag on descent. When I was testing descent in the previous blog post, I created Falcon 9 Grass Hopper looking landing legs. These had a big base for supporting the legs that provided a tremendous amount of drag on descent. The completed rocket did not have this base and hence had far lower drag when on final descent. This is the difference between a terminal velocity of ~200m/s and ~500m/s. As you might imagine, this is an extreme difference in the fuel required to land. The solution is simple, air breaks. They look slightly ugly and are slightly unrealistic, but they work.

Another possible solution to this problem is to aggressively pitch the booster side to side on descent. This way, you can greater increase average drag force on the booster. Imagine this like doing S-curves while plummeting down to the surface. Although this would be a great mix between and extremely elegent simplification of the problem and a batshit insane looking descent, air breaks were far simpler to implement. Just add them to the craft and set them to an action group, simple.

Binary Search & Lack of Landing Pads

The Kerbal Konstructs mod (I think it’s this one) I’m using to add the extra landing pads at the Kerbal Space Centre only adds three landing pads, presumably chosen for the required amount for a Falcon Heavy RTLS mission. I have 5 boosters so why don’t we just they to get them to land at the same landing site in a pattern? Very beautiful, except I was slightly off when setting the coordinates for the landing position and they where perfectly aligned. Oh well.

The previous version of the code used the Trajectories mod to find the impact location of the boosters. However, the Trajectories mod is not designed to be used with multiple craft in kOS. This emerges as a phenomenon where the scripts do not get any impact position information if I am not actively focused on the craft. Worse yet, at state changes in the code, the scripts crash. So, a solution for finding the impact location had to be found that didn’t use the trajectories mod.

Luckily, I had already created my own function for this that uses binary search to find the coordinates and time the booster would reach a particular altitude. KSP gives you information on your orbit at any given time, so with some bounds (eg. +0 and +10 minutes) and binary search, you can find the time in your orbit when you’ll be at a particular altitude (eg. 0 meters). With the time you can convert that to a position using the same orbit information that KSP provides you.

However, the KSP Orbit information is all given relative to the core of the planet. This means that it doesn’t account for the rotation of Kerbin. The simple solution to this is finding the circumference of Kerbin (2*600km*pi) and multiplying this by your eta to get an offset. This approach doesn’t take into account aerodynamic forces (I think trajectories does this), but the error is decreases as we get closer to landing so the boosters asymptotically approach the correct impact location (the landing site).

Binary Search Function found in KOS-Scripts/HelperFunctions.ks:

// Return the lat/long of the position in the future on the current orbit at a given altitude

// Ie. find the geolocation when we're at x meters above the surface in range y seconds

// SET impactGeoPos to GetLatLngAtAltitude(0, SHIP:OBT:ETA:PERIAPSIS, 10).

function GetLatLngAtAltitude {

local parameter targetAltitude. // Meters

local parameter timeRange. // Seconds

local parameter altitudePrecision. // Allowable meters from given altitude to be considered correct, can't asymptote and crash the game

// Replace 'SET' with 'Local'

// Lower bound is present, upper bound is future

local lowerBound to TIME:seconds.

local upperBound to TIME:seconds + timeRange.

local midTime to 0.

// Binary Search

for x in range(0, 35) {

SET midTime to (lowerBound + upperBound) / 2.

local midAltitude to body:altitudeof(positionat(SHIP, midTime)).

if midAltitude < targetAltitude {

SET upperBound to midTime.

} else {

SET lowerBound to midTime.

}

// If error less than precision

if ABS(ABS(midAltitude) - targetAltitude) < altitudePrecision { BREAK. }

}

local geopos to BODY:GEOPOSITIONOF(positionat(SHIP, midTime)).

// Longitude rotation of planet during coast to altitude ((360 degrees * seconds until impact) / seconds per rotation) * cos(cosine of latitude becuase of curvature)

local rotationAdjustment to (360*(midTime-TIME:seconds)/BODY:rotationperiod) * cos(geopos:lat).

return latlng(geopos:lat, geopos:lng - rotationAdjustment).

}

A Slightly More Unified Solution to Landing

In my previous blog post on kOS scripts, I wrote this:

“I imagine the solution is to track the estimated net displacement in landing position during the Suicide Burn. With the estimated time to touchdown, current pitch, and current horizontal velocity you could approximate the net displacement. Add this to the target landing location and it should be a much more accurate landing.”

This quote is in reference to suboptimal solution to final propulsive descent that I came up with in my first iteration. An issue arises when your final landing burn is not perfectly vertical. Because there is a horizontal component to your thrust, your impact position shifts closer to you. If you were originally targetting your landing site before the landing burn, this horizontal component means you’ll now land far short of it. My solution at the time was to adjust the target landing position by a constant so that we would initially overshoot, but end up landing right on target.

The addition of a constant was a very imprecise way to solve this issue. If we came it in different angles we would be off target (imagine, in the limit, a perfectly vertical or perfectly horizontal trajectory). So, the constant was just the eye-balled optimal value for an expected trajectory.

A better solution is to calculate an estimate of your net horizontal displacement during the landing burn. Then, you can add this value to your target landing location and end up far closer to the target in a wider range of trajectories.

function GetSuicideBurnNetDisplacementEstimate {

local pitchRelativeToDown to vang(ship:facing:forevector, up:forevector). // Eg. up = 0, horizontal = 90

// Iterate over every second until impact and linearly estimate the angle relative to down for every second

// With this value, calculate the difference in horizontal velocity, and add to net displacement

local localSuicideBurnLength to GetSuicideBurnLength().

local t to localSuicideBurnLength.

local netDisplacement to 0.

UNTIL (t < 0) {

local angle to lerp(0, pitchRelativeToDown, t / localSuicideBurnLength).

local xVel to SIN(angle) * ((SHIP:AVAILABLETHRUST*EstThrottleInSuicideBurn) / SHIP:MASS). // F/m = a, thrust in kN, mass in tons / mega grams / kilo kilograms you get kN/t or N/kg, so the formula works

SET netDisplacement to netDisplacement + xVel.

SET t to t - 1.

}

return netDisplacement.

}

Above you can see the code for this estimated displacement function.

It works by getting your current pitch relative to vertical. It assumes you decrease your pitch linearly as you come in for landing. With this assumption, it steps through second by second to calculate your horizontal velocity at each step and takes the sum of these velocities to get your net displacement. This is a slightly shitty implementation and I didn’t know the meaning of the word integral when I wrote this, but it works (mostly).

The “mostly works” part is adjusted for by another constant! Use this one easy trick to solve all your problems! Just add another terms! You can see the EstThrottleInSuicideBurn variable in the function above. We need to know our average throttle during the landing burn to get an accurate displacement result, and that’s what this value represents. I set it to 1.5 (150%) in the config file for the boosters (KOS-Scripts/Dzhanibekov/DzhanibekovBoosterEast.ks). This is not quite a real value because we of course never expect more than 100% throttle, but I experimentally found it to be the proper value. A common theme in this project is experimentally finding proper parameters mostly because the experiments here are watching rockets land!

The config file for the boosters contains slightly more information than just the estimated throttle during the landing burn. It also contains the pitch multiplier that specifies how much the boosters should pitch to minimize error between intended landing site and impact position, craft height, and other variables. This “config” file isn’t quite a config file because kOS doesn’t allow this (shitty language). So, it also has the code to handle staging and running the landing script after the boosters have separated from the core.

I’ve covered the most important parts of this project, If you have questions, DM me.

MERRY CHRISTMAS!!! 🎄🎄🎄