Small Sat Constellations: The line between Electron and Rideshare

If you have any feedback or criticism, please reply here.

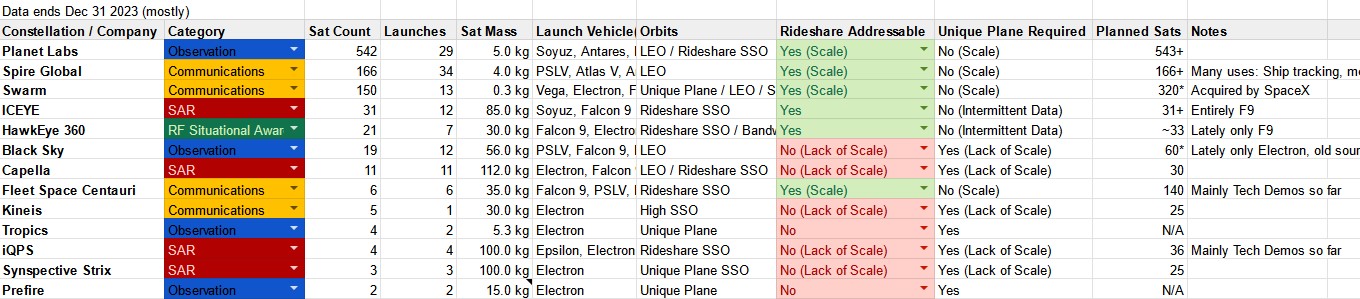

Which Constellations Require Dedicated Launches?

Constellations that have a relatively small number of satellites and require high & regular revisit rates are well-suited for dedicated launches. Many of the recent Synthetic Aperture Radar constellations fall into this category such as Capella, iQPS, Synspective, and Black Sky (Earth Obv). These constellations benefit from high & regular revisit rates so they can provide near real-time data to their customers and cover specific parts of the Earth regularly (eg. once every half hour).

Recently there’s been a great example of the Commercial benefit that dedicated launches provide: Synspective signed a 10-launch deal with Rocket Lab. Given an Electron average sales price of $8M, this is a $80M contract. The cost of a SpaceX rideshare mission is an initial charge of $300k for 50kg to SSO with each additional kilogram at $6k. Assuming Synspective launches 2 100kg Strix satellites per Electron this is 20 satellites in total. On SpaceX rideshare missions this would cost $12M, a $68M cost delta.

Launch schedule is another factor to consider when analysing Synspective’s choice to go with Rocket Lab. The Electron launches will occur between 2025 and 2027. SpaceX rideshare missions are rumoured to be booked 2 years out and they launch 3-5 times per year (Up to 5 with Bandwagon rideshare missions). Assuming a start date in 2026, Completing 10 launches for Synspective could take SpaceX until 2028 or 2029. However, this time can be shortened if the satellites have sufficient on-board propulsion to change their orbital planes (This is covered in the final section). Even assuming the schedule issue is resolved with a higher scale in the future, rideshare missions still mean suboptimal orbits.

The cost advantage of rideshare missions is cancelled out by the schedule (temporary) and orbit/delivery (permanent) disadvantages. One of the primary disadvantages of rideshare missions is having to negotiate with several other companies on which orbit the satellites will be deployed into. This means every customer is not where they want to be and on top of the schedule disadvantage, this means each satellite is initially producing less revenue than it otherwise could be. In the case of Synspective, the advantage of launching on Electron appears to be worth at least $3.4M.

Prefire and Tropics do not fall into the category laid out above because they are made of 2 & 4 satellites respectively and will not be expanded in the future. Unlike commercial constellations, these are one-off NASA constellations that serve a very narrow and specific Earth Observation purpose. So, there will not be an increase in demand for the data these satellites provide. When new data is needed, NASA will develop and launch a new set of 2-10 satellites.

Rideshare Missions Launch Most Constellations Satellites

The first category of Small Satellite Constellations that launch on rideshare missions are those with such high scale that the exact orbits of dedicated launches are not required. These include Planet Labs, Spire Global, and Swarm (before SpaceX acquired them). Planet Labs has 542 satellites, Spire has 166, and Swarm had 150 before acquisition. Given the number of launches required to deploy these constellations, you get a large enough distribution of orbital planes that you can cover all of the Earth with a high revisit rate. Given the falling price of launch, creating satellites cheap enough to produce hundreds so you can utilize rideshare missions could be a winning strategy (Like Planet Labs).

The second category is constellations that don’t require the revisit rate benefit of dedicated launches (even spacing of orbital planes). HawkEye 360 is the best example of this as this is one of the few constellations that is not focused on Earth Observation or communication with Earth-based assets. They sell Radio Frequency signal location data. This process involves detecting RF emissions and triangulating the source with multiple satellite passes over the same location. This means the orbit requirements are not as strict as other constellations. In contrast to the Synspective example in the previous section, HawkEye 360 does not get as much direct monetary benefit from dedicated launches. They recently cancelled a few of their upcoming Electron launches.

One of the great benefits of rideshare missions (even to Electron) has been the ability to launch test satellites for a low cost. Many early Capella and BlackSky satellites launched on Falcon 9 and this allowed for cheaper development of their constellations which ended up launching on Electron. This allows for cheaper launches during the early scaling of the constellation and an accelerated completion timeline.

The Market for 1-Ton Class Launch Vehicles

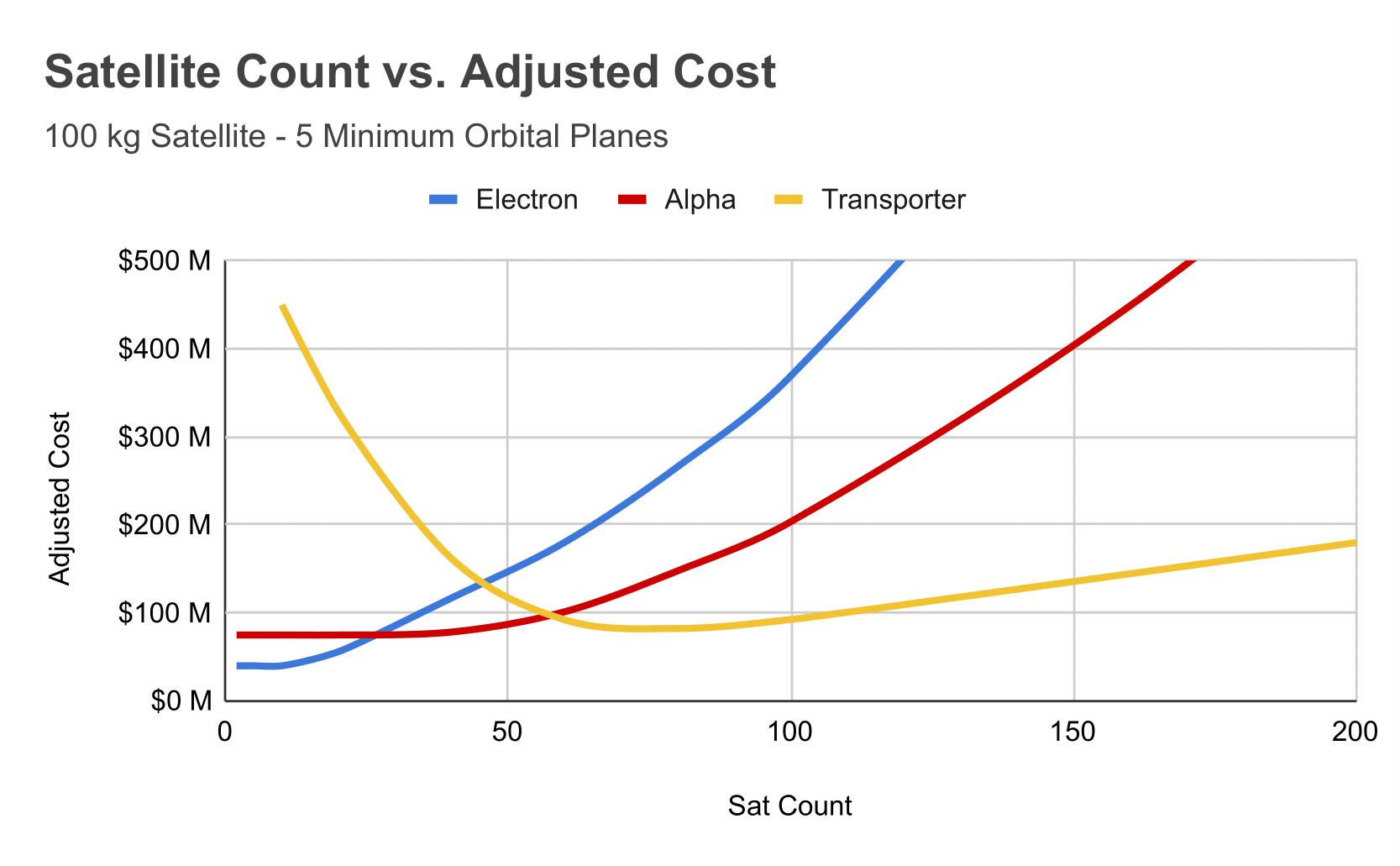

Just like Falcon 9, Electron owns the small sat market because there are no capable competitors. Over the next few years, we’ll see Firefly ramp up its Alpha launches and ABL’s RS1 come online (hopefully). From a product perspective, these 1-ton class rockets have the potential to take market share in the small-sat constellation launch market. Ozan Bellik pointed this out when I mentioned my blog post Comparing Demand for Firefly’s Alpha vs. Electron. My conclusion wasn’t completely incorrect, but inaccurate enough to warrant this section.

The niche of the market that these vehicles can solve is constellations with ~100kg satellites that plan to launch more than 20-30 satellites. These include iQPS, Synspective, Capella, and BlackSky. Alpha and RS1 cost around $15M which is ~2x more than Electron while having ~4x the payload capacity. On the surface, this appears to be a 2x improvement in $/kg, but the entire capacity of the rocket may not be used. Using the entire 1000kg of payload capacity would mean launching ~10 satellites at a time which negates the advantage of having satellites spaced out in different orbital planes which lowers revisit rates which in turn makes a constellations offering less competitive with other Earth Observation companies, ie. lower revenue. The breakeven point for a 1-ton class rocket vs. Electron occurs when 4-6 100kg satellites are launched on a single mission, 2x the payload for 2x the cost.

Rocket Lab has the massive advantage of high cadence and a proven track record, so in reality, the breakeven point from a constellation operator’s perspective goes even higher. The massive first-mover advantage Rocket Lab has today translates to other aspects as well. In Peter Beck’s recent interview with Eric Berger in reference to constellation customers he said: “They’ve designed their constellation or their spacecraft around Electron. It does things that you just can’t get on other missions.” Given the size of recent constellations in both individual satellite mass and the total number of satellites, it’s clear that Electron is the best option and is being optimized for by the industry. It will take many years for the advantages of 1-ton class rockets to be fully realized by the industry.

iQPS’s upcoming constellation may be the only one out of the 7 dedicated-launch-addressable constellations in the chart that could reasonably fly on a 1-ton class launch vehicle. According to Gunter’s Space Page (Amazing source) they are planning a constellation of 36 100kg satellites. With 6 launches on a $15M 1-ton class rocket, this could be competitive with Electron. The other constellations either have satellites that are too light to warrant anything other than Electron or too few planned satellites. Too few satellites mean unoptimized coverage of the Earth if launching too many at once, ie. lower revisit rates.

Given the lack of constellations launching in the next few years that would see a large enough benefit from 1-ton class rockets, it’s unlikely Alpha and RS1 will reap the benefits of their size & cost per kilogram advantages until the late 2020s. Assuming constellation design shifts to the 1-ton class instead of Electron due to cost, there is a world in which they get 50% or more of the market. However, at a certain size of constellation rideshare missions become competitive.

The Future of Launching Small Sat Constellations

There is zero chance Electron loses a significant number of launches to another rocket in the next ~3 years. As Peter Beck said, they are the industry standard in small satellite launch and the industry is building around the capability Electron provides. However, in 5+ years if the 1-ton class rockets succeed, there will be more room in the industry to design larger satellites that take advantage of the cost per kilogram advantage of these rockets. The lower cost of mass also allows for heavier (cheaper) materials to be used, lowering satellite costs even further. This is however not a paradigm shift as it is mainly a marginal improvement. There is enough space for Firefly or ABL to succeed in the market, but it’s very unlikely they displace Electron. The market will grow to support more companies, market share may be lost, but there will be net growth. Rocket Lab enabled the small sat business while Firefly and ABL are merely improving it.

Rideshare missions will soon have the ability to eat even more of the dedicated small sat constellation launch market when kick stages come online and propulsion becomes cheaper. The two main advantages of dedicated launches are schedule and orbit precision, all other benefits stem from these points. Schedule will remain a benefit of dedicated launch but orbit precision can be addressed by kick stages or on-satellite propulsion.

Sun Synchronous Orbits precess around the Earth which is the mechanism that allows them to always stay in the sun, otherwise, there would only be a few days per year in which the polar orbit is 100% exposed to sunlight. This same principle makes it possible to shift the orbital plane of a satellite with minimal fuel expenditure through slightly increasing altitude and changing the inclination of the orbit. This process can take up to several months or if the launch is already near the desired orbital plane a few weeks is possible. Either way, revenue is delayed. However, for mature constellations, revenue delay is less of a concern and millions of dollars per satellite can potentially be saved.

Either space tugs like Impulse’s Mira or ion thrusters on each satellite can accomplish the low-energy polar orbital plane change. Ion thrusters have the advantage of providing efficient propulsion that can extend the satellite’s lifespan. Starlink satellites currently use Argon ion thrusters to boost themselves to their final orbit. With 2500 seconds of isp, they are far more efficient than chemical propulsion, meaning more mass can be delivered to the final orbit. As always, the limiting factor here is the cost. This is possibly offset by a longer satellite lifespan, but it remains to be seen how many constellations opt for this route. In the next 5-10 years we will see.

The advantage of ion propulsion is best seen on large constellations like Starlink, OneWeb, or Kuiper. This may have an impact on the industry as we see convergence to an end-to-end model. In the case of Rocket Lab, this could mean manufacturing their Lightning satellite bus with ion propulsion to host many different payloads. This allows for the benefits Starlink has seen with a common satellite bus and launch vehicle while serving multiple customers. While Rocket Lab sees competition from 1-ton class rockets and potentially Stoke’s Nova, they will be transitioning to hosting payloads on a common satellite bus where Neutron and Space Systems take over from Electron on constellations.

Updates

[Update Apr 24 2025]

In this Space News article by Jeff Foust,