A New Paradigm of Launch Vehicle Architecture Design Tradeoffs

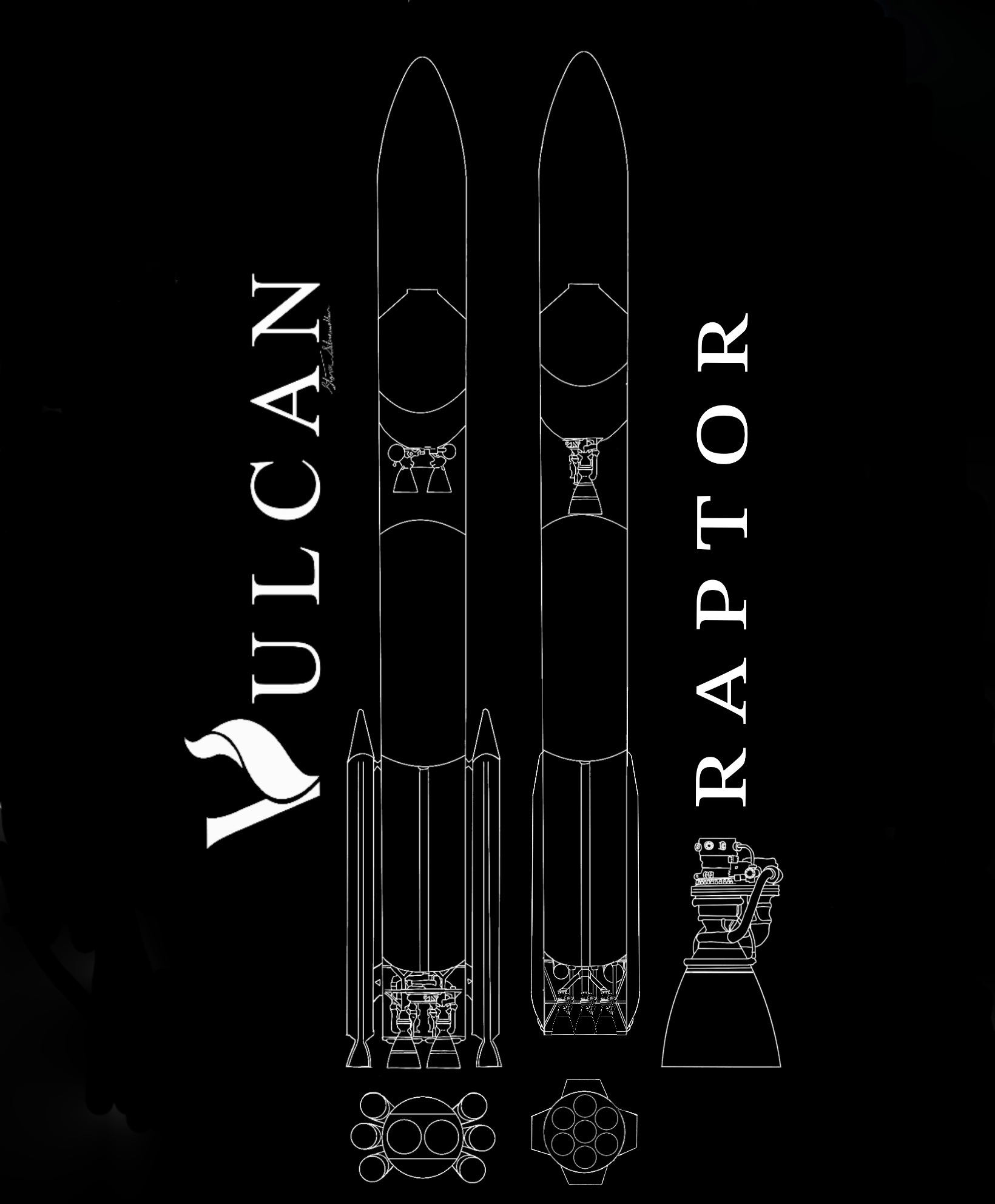

This image I got from @StormSilvawalk1’s reply illustrates the two paradigms well. One of these vehicles (Vulcan, left) has 10 separable vehicle parts (SRBs, stages, fairing etc.) vs. just 2 for a vehicle like Starship or Neutron.

We are currently living through a paradigm shift in launch vehicle architecture design. We are seeing old space companies like ULA or Ariane Space that are used to building highly customizable vehicles try to adapt to a new paradigm of reuse and high flight rates. Every day we continue to see these legacy perspectives bump up against new ideas that are optimized for different requirements. These companies once had extremely successful business models, but now they are struggling to adapt to the new paradigm of launch vehicle design, sometimes resulting in laughable concepts.

We’re Seeing a Paradigm Shift From Customizable Vehicles to Vehicles Focused on LEO

The old paradigm of vehicle design was optimized for infrequent launches to a variety of orbits. The Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) program vehicles are great examples of this. The Delta IV and Atlas V were both optimized to have a wide range of configurations to meet the various target orbit and mass specifications that the US government laid out. This led to 11 flown configurations (according to Wikipedia) for the Atlas V and 5 flown configurations for the Delta IV. These configurations varied the number of boosters and size of the fairings and were the proper tradeoff for the requirements that Boeing and Lockheed Martin were given at the time.

The new paradigm ushered in by SpaceX’s Falcon 9 is focused on reuse, high flight rates, and standardizing your vehicle for a specific orbit. Falcon 9 was originally optimized only to deliver the Dragon capsule to the ISS which is in Low Earth Orbit (LEO). Now, its primary use is launching the Starlink satellites to LEO. To a first approximation, Falcon 9’s architecture is solely focused on getting as much mass to LEO as possible. Starship shows this goal even more clearly. It is a vehicle architecture that is completely focused on getting as much mass to LEO as possible. This means that through reuse and an extremely high flight rate they can achieve low cost, and then leverage refilling missions to get to Mars or other high-energy destinations in the solar system.

The Paradigms Decide Vehicle Architecture Optimizations

Both the old paradigm of vehicle customizability and the new paradigm of achieving low cost through reuse and high cadence are sound given their respective requirements (reaching EELV target orbits vs. getting tons of mass into LEO). However, issues start to arise when the companies that were dominant in the old paradigm try to adapt to the new paradigm.

Legacy space companies like ULA or Ariane Space are used to building customizable vehicles (varying booster counts or fairing sizes) because this was the most economical way to launch all the payloads they were tasked with launching. It is unfortunate to waste a full vehicle rated for 20t when your payload is only 10t, so instead you rate your base vehicle for 10t and add boosters onto it to be able to launch 20t. Atlas V took this to an extreme with some of its launches using only one booster (imagine that offset thrust)!

This approach has no place in the paradigm shift to reuse. Because the Falcon 9 is capable of booster reuse, SpaceX is not particularly impacted by whether their payload is 2t or 20t, they get the booster back either way so they have no reason to spend all the money required to create 10 different variants for different payload classes.

A defining characteristic of this paradigm shift is the approaches to lowering the cost of missions. The legacy model was to use as little hardware as possible for a given mission to save money (hence the 11 Atlas V configurations). The new model is to use a standard vehicle for all your missions to save money. This is because the primary cost savings of reuse come from high cadence (this was part of the reason the Shuttle was never cheap). Flying a standardized vehicle for all your missions has immense value in the cost savings the high cadence provides.

With the partially reusable Falcon 9, there are still some areas where SpaceX doesn’t get cost savings from high cadence and they revert to the old model of using as little hardware as possible to decrease cost. For example, on Transporter missions, they use a shorter Merlin engine nozzle extension to save the cost of the Niobium.

Looking into the future, SpaceX is fully bought into reuse and the result is they are developing a single vehicle that they can throw at every problem. With Starship they’re again going all in on a single vehicle and throwing it at every problem.

Everyone on X already understands all my points intrinsically through memes. A meme is worth a million words, and it spreads as a mind virus.

Not Having Full Buy-in To The New Paradigm Explains All The Foolishness We’re Seeing

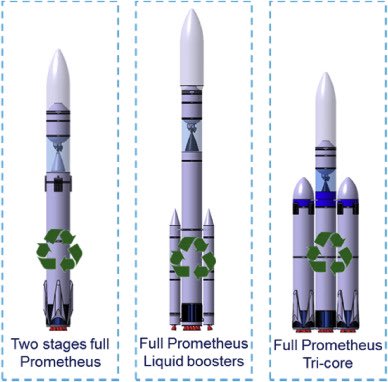

The Ariane NEXT concept illustrates why Ariane Space is not adapting to the new paradigm well.

There is this hilarious, infamous clip of an Ariane Space exec saying SpaceX’s plans are a dream and if they ever come true that Ariane Space will be quick to follow. This is a phenomenon of believing the current paradigm of launch vehicle design will continue long into the future and a belief that Ariane Space would be fast enough to keep up with any paradigm shifts. Both of these points turned out to be false, hence why this clip is hilarious.

One of Ariane Space’s concepts for a reusable vehicle is Ariane NEXT. The end goal of Ariane NEXT is a partially reusable 3-core vehicle, similar to Falcon Heavy. One of the interim steps described in a paper on the concept (Section 4.2) is to have smaller liquid boosters based on the same engine to increase the payload capability of the vehicle. There is also some discussion of a hydrolox upper stage, while the standard vehicle is methalox.

The Ariane NEXT concepts are an example of Ariane Space still thinking in the old paradigm of having a highly customizable vehicle. Instead of completely buying into having just a single vehicle (or at most 2 versions like Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy), they want to have 3+ versions (single core, small boosters, large booster, plus a potential hydrolox upper stage). This is an approach that will not get them the cost savings of having a single standard vehicle (like the Falcon 9 booster).

The architecture of the Vulcan rocket shows that ULA is another old-space company that isn’t adapting to the new paradigm well. Vulcan is a customizable vehicle in that it can have 0, 2, 4, or 6 solid boosters. Almost as an afterthought, they included some reuse in the design with their SAFER concept, that decouples, reenters (with an inflatable heat shield), and parachutes the engines back to Earth. This shows even less buy-in to the new paradigm, as they are seemingly trying to reuse as little of the vehicle as possible while keeping the ability to add solid boosters to increase payload capability.

The new paradigm of reuse incentivizes a single vehicle that can be reused as much as possible for all missions. ULA’s Vulcan architecture is not optimized for this. Like I said in the first section, these design decisions make complete sense if you’re operating in the old paradigm, but they are not the right tradeoffs for the new paradigm. Vulcan is optimized to launch US Military payloads through the NSSL program, but not to launch as much mass to LEO as possible which is the requirement for upcoming megaconstellations (See the Constellations - The Next Paradigm section). When launch is no longer extremely supply-constrained, it will become clear that Vulcan is not optimized for competing with vehicles optimized for economical reuse.

Conclusion

The fundamental issue with Ariane Space’s and ULA’s approaches is that the new paradigm of reuse and high flight rates incentivizes integrating as much onto a single reusable booster as possible. Don’t have solid boosters, just make your core bigger and get good at reuse. Don’t even have separable fairings! Integrate those onto a reusable stage so reusing them is even easier!

ULA and Ariane Space have clearly not committed to this new approach and are hanging on to the old paradigm of having a highly customizable vehicle. This approach may work for them in the short term as they have government support, but in the long term, it will become clearer and clearer that this approach will not be commercially competitive with other vehicles optimized for reuse.

Updates

[Update Jan 12 2025]

Casey Handmer explains the issues with increasing the number of vehicles your architecture uses in this blog post. It’s a good read to get more context on this issue and described the issues with increasing the complexity of you architecture well.

[Update Jan 12 2025]

Another way to consider the paradigm shift I described is architecture complexity vs. launch cost (ie. do you make more vehicle configurations or just make a single vehicle that is oversized for most tasks that’ll be cheaper through reuse).

[Update Apr 7 2025]

Again, Casey Handmer hits the nail on the head with this article:

“The superpower of Starship is replacing a menagerie of expensive limited bespoke vehicles for tentative, programmatically brittle human Mars exploration with a single, unified, powerful robust system.”