Most Profilic Space Station Modules

Source data for my charts is available in this Google Sheet and in this repo.

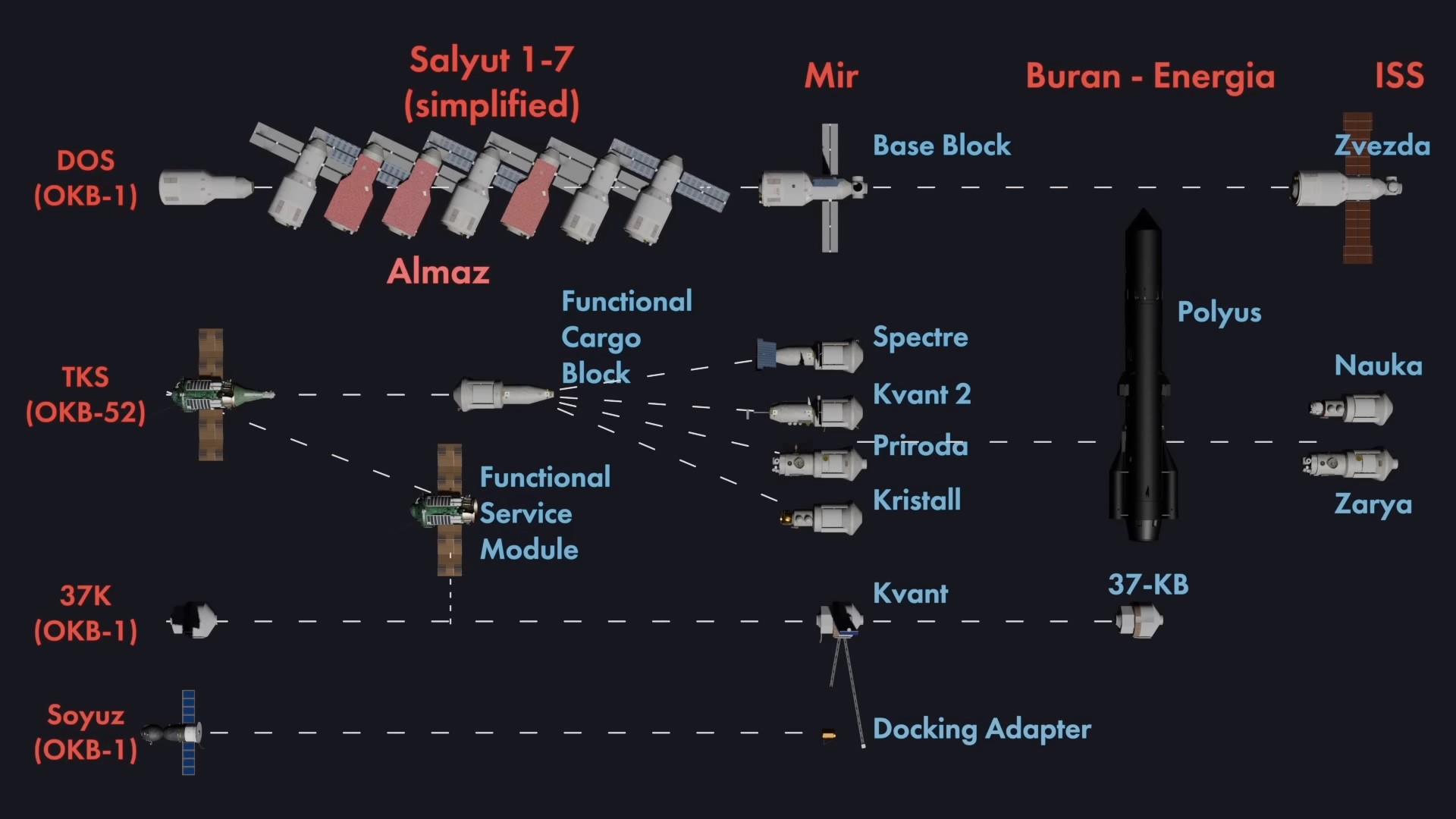

Alexander the ok’s Beautiful Soviet Space Station Timeline.

Today Alexander the ok released a video on the Soviet Almaz stations. In the video he said this: “After the Almaz OPS hull, TKS cargo blocks are the second most prolific space station module design ever launched.”

I was immediately and irresistibly nerd-snipped by this statement and I had to write the blog post to tell the story of the most prolific space station module families ever flown.

TKS and Almaz

First, I’ll give some background on the TKS and Almaz-derived station modules.

Almaz was a program in the Soviet Union to develop a series of space stations for mainly military reconnaissance purposes. Each station weighed around 20 tonnes, had an 88cm diameter cosmonaut-operated telescope (1m surface resolution), and was launched on the Proton rocket. The Almaz station was based on the Orbital Pilot Station (OPS) hull and was well into development in the late 1960s.

In 1969, with the Apollo 11 Moon landing and the Soviet Moon Rocket, the N1, failing, the Soviet space program shifted its focus from the Moon to space stations. OKB-1 - a design bureau formerly run by Sergei Korolev - acquired (“or stole” according to Alexander the ok) several OPS hulls from the OKB-52 design bureau (They developed Almaz and the Proton rocket used to launch it). After refitting the OPS hulls with Soyuz spacecraft electronics and hardware (And renaming the station from Almaz (military-focused) to Salyut (civilian / science-focused)), the world’s first space station was launched on April 19 1971.

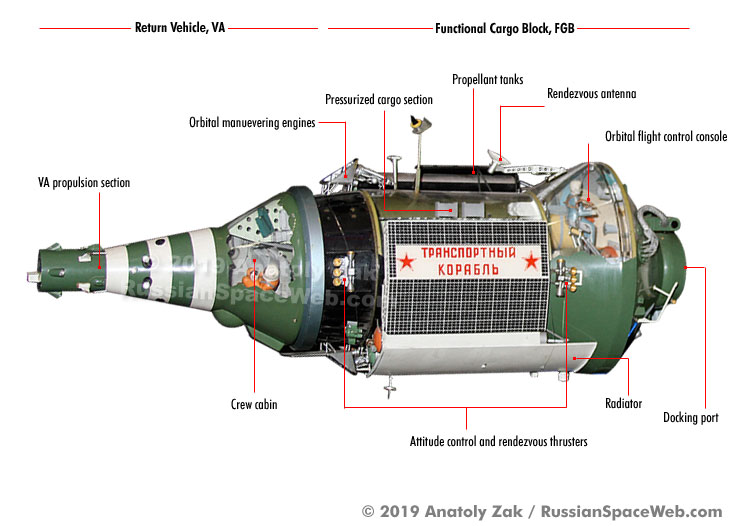

Diagram of the TKS spacecraft courtesy of Anatoly Zak of russianspaceweb.com, which you should check out!

TKS (Transport Supply Spacecraft) was a Soviet spacecraft designed and flown in the 60s and 70s. It was designed to carry crew and cargo to the Salyut space stations. 3 of them were launched and docked to the Salyut 6 and 7 space stations.

The TKS spacecraft consisted of a crewed capsule and a cargo module. TKS was never launched with crew, but the cargo module evolved into the Functional Cargo Block (FGB, transliterated from the Russian initialism ФГБ), which was used as the core module on the Mir space station and the ISS. I’m using TKS as the name of this family of modules, and including the TKS capsules that flew to Salyut 6 and 7 in my analysis.

For a nice dry and technically dense (in a good way!) read of the early Soviet Space Program, I recommend The Almanac of Soviet Manned Space Flight. I say dry in a good way in contrast to books like Eric Berger’s Liftoff or Reentry (stories of the Falcon 1 and Falcon 9). These books are the stories of the people and stories behind SpaceX’s early rockets, while the Almanac is a technical history and timeline of the Soviet Manned Space Program (written in the US in the 90s!).

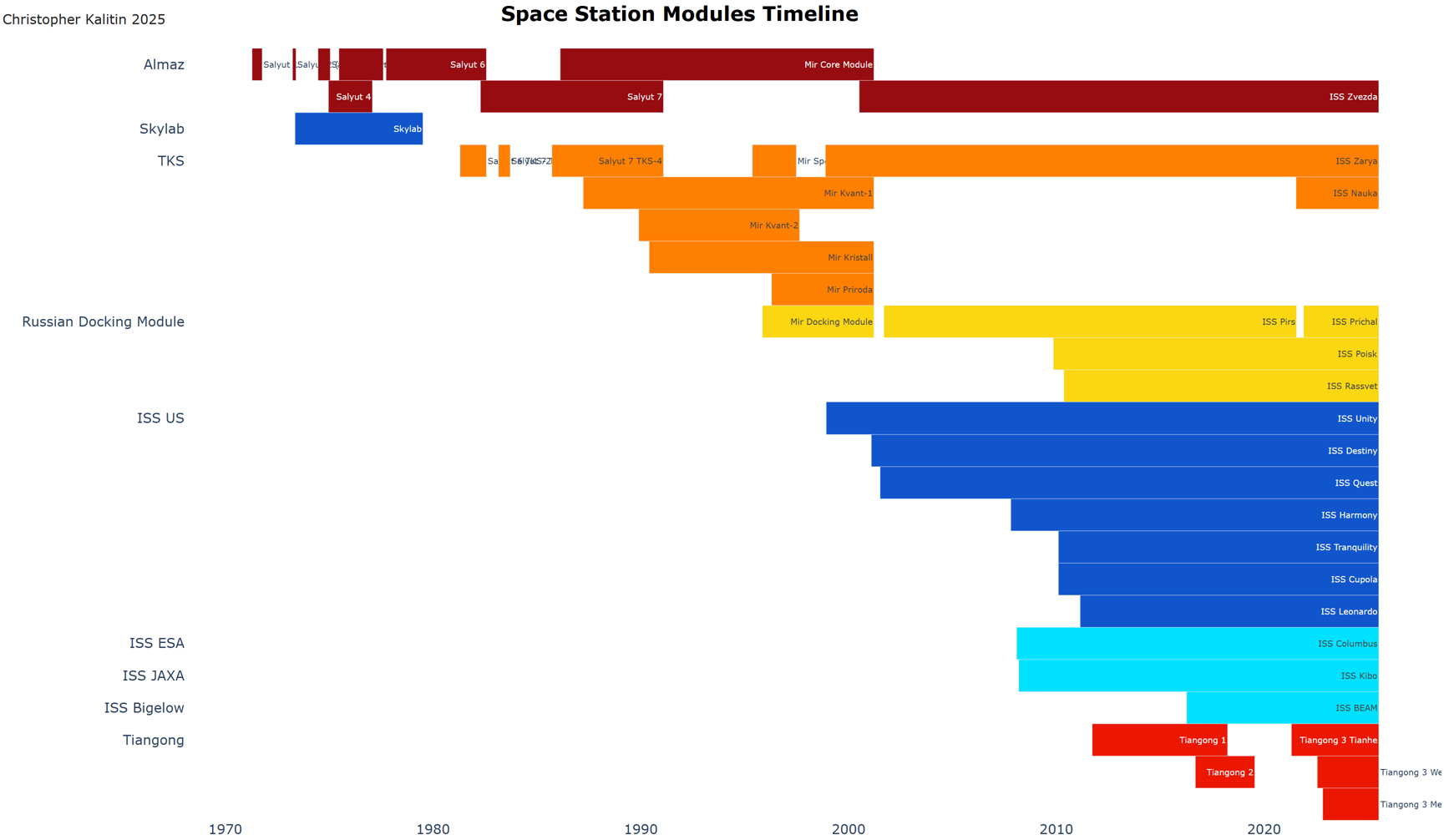

Overview Of All Space Station Module Families

I’ve sorted all space station modules into seven primary families:

- Almaz

- TKS

- Skylab

- Soviet / Russian Docking Modules

- US ISS Modules

- International/Commercial ISS Modules (Bigelow, ESA, JAXA)

- Tiangong

You’ve heard of Almaz and TKS now. Skylab was the US’s first space station, launched in 1973. It was a modified Saturn V third stage and the final flight of the Saturn V rocket. Three crews visited the station.

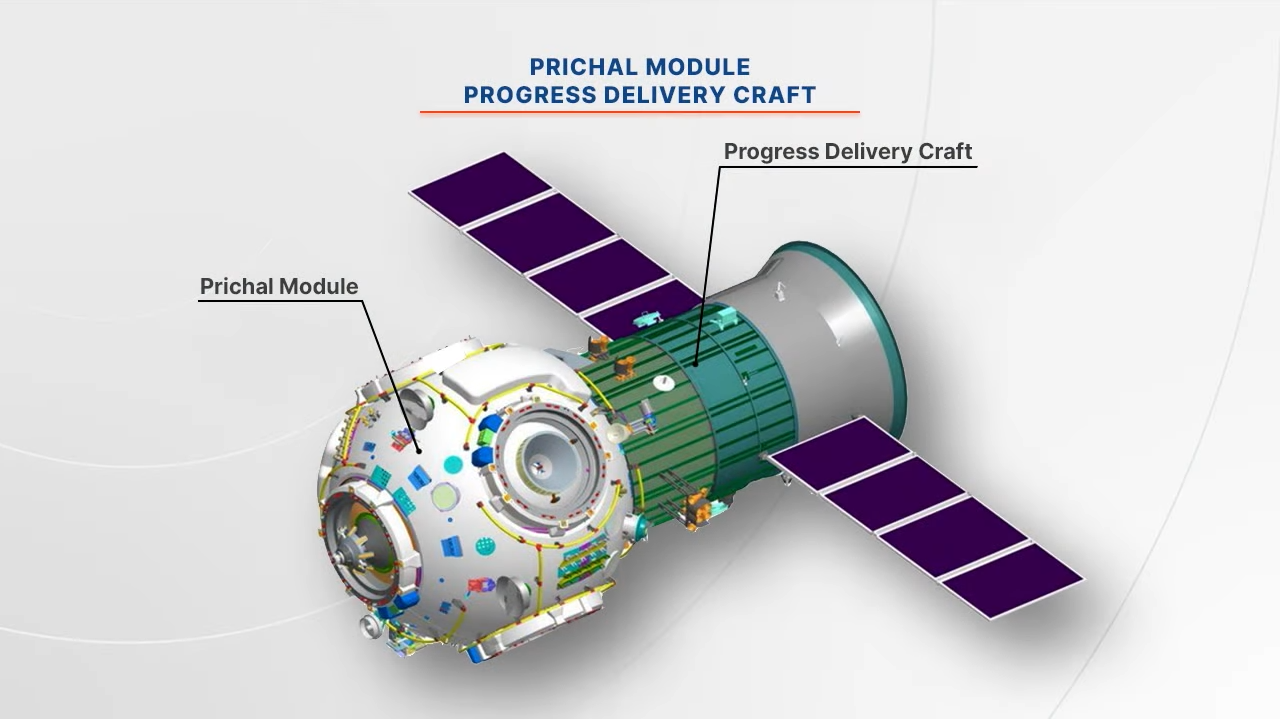

Five small modules were launched to Mir or the ISS as docking / small scientific modules. One of these flew to Mir, and four of these to the ISS (Pirs, Poisk, Rassvet, Prichal). All but one of these were launched on Soyuz rockets as they used the Progress spacecraft’s service module for propulsion and docking to the ISS. The odd one out is Rassvet, a “Mini-Research Module” that was launched on a Space Shuttle flight.

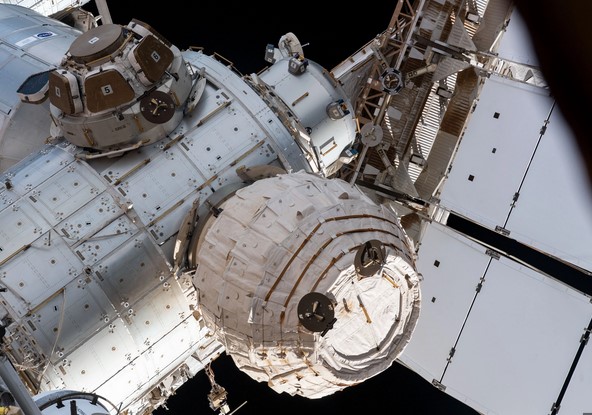

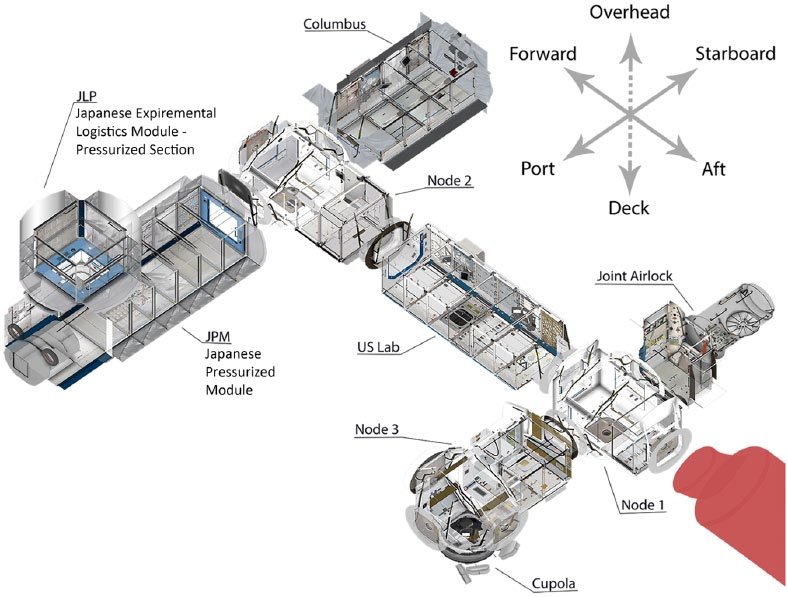

The US ISS modules are the ones you’ve heard of (Unity, Destiny, Quest, Harmony, Tranquillity, Cupola, Leonardo). Jared Owen has a great video on the assembly of the ISS, which you should watch if you want to know more about these. I’m counting all of these as a single family. This isn’t quite right because they aren’t all based on the same hull like the Almaz or TKS modules, but it was all for the same station by the same space agency, so I’m counting them as one family.

The international / commercial ISS modules are BEAM (Bigelow Expandable Activity Module), Columbus (European Space Agency, ESA), Kibo (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, JAXA), and BEAM (Bigelow Expandable Activity Module). BEAM was developed by Bigelow Aerospace and launched on a SpaceX Dragon resupply mission to the ISS before they went bankrupt. It was an inflatable module.

Tiangong is a series of 3 Chinese space stations. The first two were small, short-lived stations that were launched in 2011 and 2016. The third one is a modular space station with three modules at the moment. The Chinese are planning a fourth free-flying space telescope module. Very cool and we need to accelerate.

Plotting Space Station Families

CLICK HERE for the beautiful raw html interactible plotly chart as some names were cutoff or too small to read.

Everything you’ve read up until now is background that anyone could have told you. Now onto my analysis and charts that I made.

Above is a GANTT chart of all space station modules colour coded by family. I love beautiful visualizations like this please steal if you want to show your friends.

In dark red in the top left, you see the Salyut / Almaz stations. These came roughly sequentially, one after the other.

With the first modular space stations, Mir and the ISS, we see a lot of modules launched in parallel taking up most of the graph. You can see the Mir modules in orange towards the center of the image and the ISS modules in orange, yellow, light and dark blue towards the right end of the image.

At the bottom right in red, you can see the youngest space station (Until Vast’s Haven 1 launches!) - the Chinese Tiangong space station.

%20vs.%20Station%20Module%20Family.png)

Next, I used this data to plot out the net lifetime of each module family. We see that the US ISS modules have combined more lifetime than any other family of modules. Judging off my criteria of all US ISS modules being one family, Alexander the ok’s statement is incorrect. TKS and Almaz are both behind the US ISS modules.

However, again, it isn’t quite proper to say all of these modules are of one family. Looking at the diagram of US ISS modules above, we see that every module is distinct and serves different purposes. They were developed in parallel for the same station, but aren’t identical hulls like the TKS and Almaz modules. You get away with it this time Alexander the ok!

Another unexpected result is that the small Soviet / Russian docking / mini-research modules have just slightly more lifetime than all Almaz modules. This makes sense once you consider that Mir and ISS have decades of lifetime while the Almaz-derived stations (Salyut mainly) were only flown for a few years each.

%20vs.%20Station%20Module%20Country.png)

Sorting by country, we see that Russia has the most net space station module lifetime, followed by the US and China.

Russia has 74,269 days.

The US has 52,636 days.

China has 7,015 days.

The ESA has 6,364 days.

Japan has 6331 days.

How Long Until We Beat These Records?

The US currently has 7 modules in orbit, Russia has 6, China has 3, and Bigelow, ESA, and JAXA have 1 each. This means the US is gaining one module day per day on Russia in terms of the net lifetime of space station modules. With the current difference of 18,252 days, it will take the US 50 years and 2 days to catch up.

If Vast succeeds in fully assembling their Haven 2 space station, they will have 9 modules in orbit. This is part of NASA’s Commercial LEO Destinations (CLD) program, and it will hopefully be a successor to the International Space Station. At 9 modules (9 module days per day), it will take them 22.6 years to catch up to Russia’s 74,269 days of net module lifetime.

I hope we move away from a module-focused paradigm of space stations in the future and towards monstrous structures housing millions of people in space. At this time, module days won’t be a valuable metric. I predict that in a few decades, I’ll write a blog post on human-days in space per space station family, and I’ll be working in thousands of human days per day.