The Transition to EV Robotaxis

- S-curves (show them, and why they’re the future) “S-curves are destiny”

- Personal arguments do not matter, economics does

- Implications (less car ownership, new auotmotive market decreases, majority of income from software, first mover advantage?, bankruptcies, adjacent technologies, other transport methods that can’t compete, clean future)

- Kurzweil quote about applying paradigms

-

All our problems will be solved through due to economic reasons

- EV revolution (S-curves, declining costs, Cross over point, Graphs, companies, etc.)

- Autonomous revolution (Predicting pace of AI, adoption in new vehicles (OEMs), retrofitting, potential first mover advantage, etc.)

The automotive market is currently undergoing a transition from privately-owned internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles to autonomous EV robotaxis.

There are three components to this transition: ICE to EV, Manual to Autonomous, and Privately-owned vehicles to Robotaxis.

The transition to EVs is easily explained from an economic perspective.

The transition to autonomy will occur mainly due to leasure and safety reasons from the consumer’s perspective.

The final transition from privately-owned vehicles to robotaxis will occur due to the improved ease of use of Robotaxis.

“S-curves are like gravity” - Tony Seba.

These transitions can be seen to be as likely as the sun rising tomorrow. Many society-level problems are economics problems, and economic predictions can be immensely accurate.

EV Revolution

The EV S-Curve

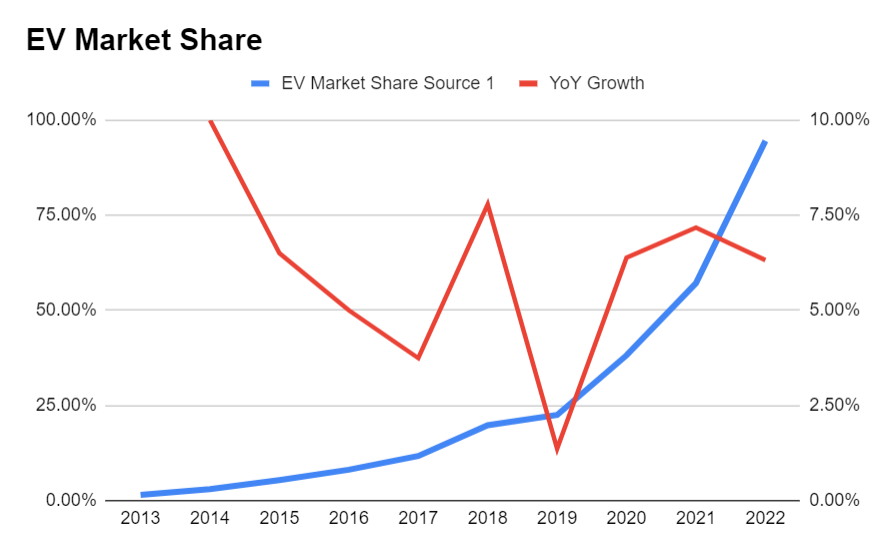

Currently, the EV revolution is occuring at fervent pace. This is mainly due to economic reasons and is occuring both in personally owned vehicles and commercial/heavy vehicles.

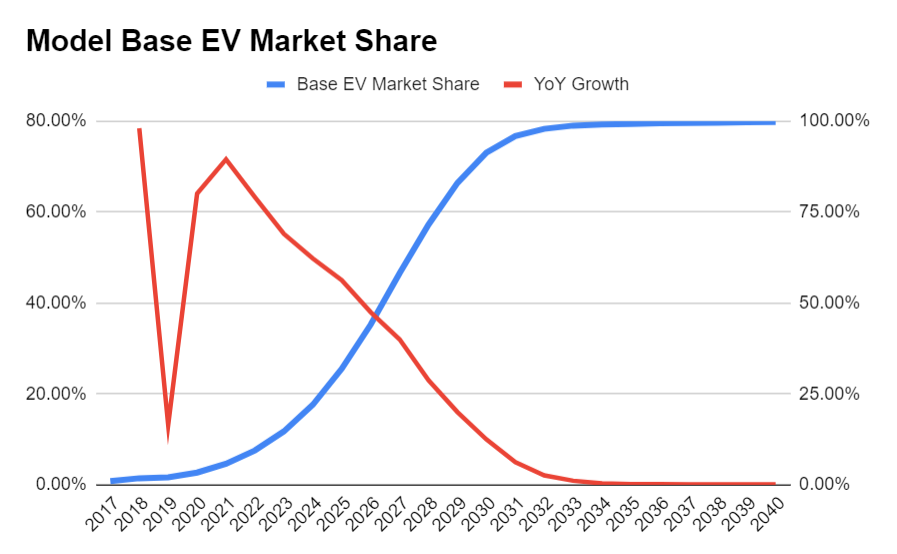

It appears growth in EV adoption has peaked in 2014 and has been sporadically declining since. This is to be expected and is visible in many other S-Curves. As any technology matures and the market becomes saturated, growth slowes. The decline in growth is not an indictment of the technology, but rather a sign of its maturity. The decline in growth serves to help identify when the technology will reach its peak market share, which in almost all cases is >99%.

Above is my prediction for EV market share until 2040, the 50% mark is in 2027 and 90% in 2030.

This is an economics problem so it can be solved with an economic toolkit. Personal arguments do not apply here, your uncle from Alabama will bregrudingly buy an EV when he realizes how much he’ll save, or he’ll be in the 1% of people who don’t. You can not support major automakers on 1%.

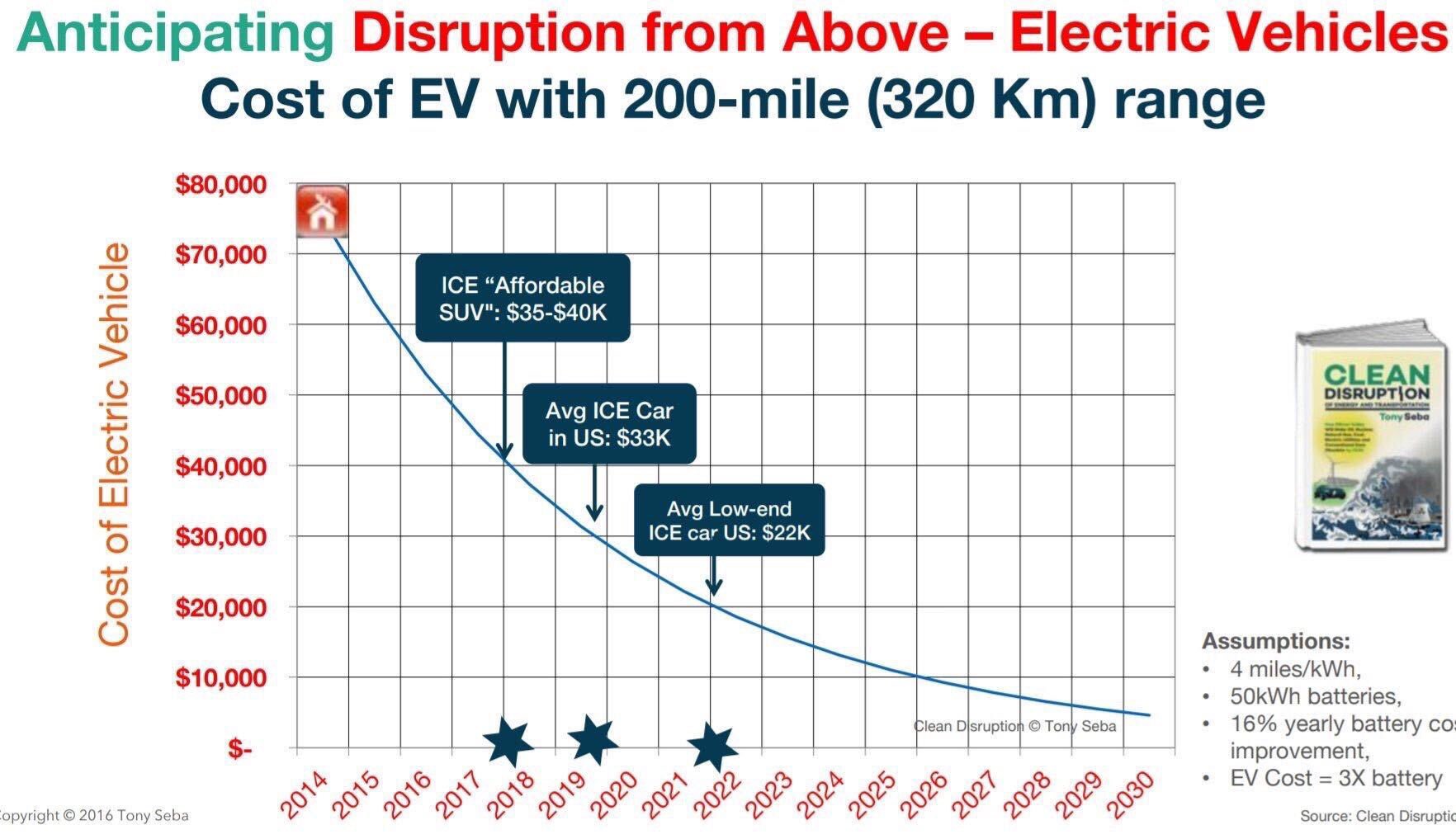

Decline in EV Manufacturing Costs

Almost all the major internal components of EVs are declining in cost.

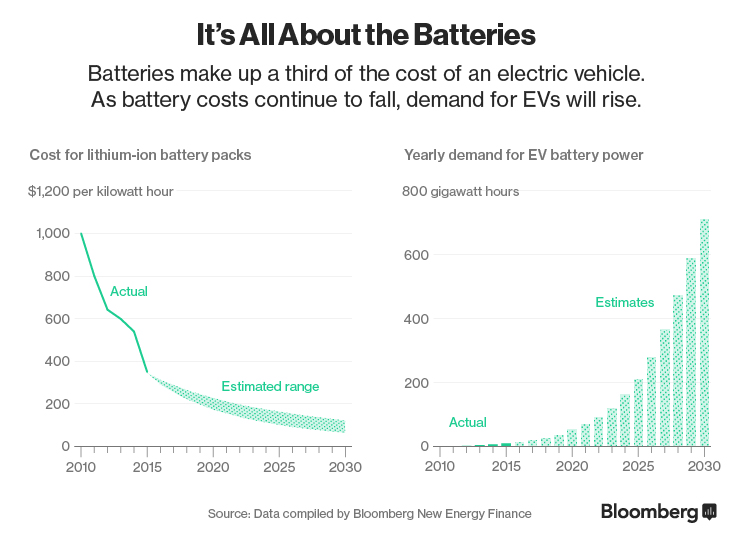

This is most obvious in battery costs. Batteries have been on a declining cost curve for almost all time. This is due to advancements in materials science, battery chemistry, and economies of scale.

The cost of EV specific components other than batteries, such as electric motors, will also decrease in cost primarily due to economies of scale. This shows that reaching scale manufacturing of EVs is a key component to success. Speeding up transition plans from ICE to EV is the best strategy.

When taking into account all the declining costs of the underlying components, we are on track for immensely cheap EVs that out perform ICE vehicles in almost every metric. Internal combustion engines are a mature technology; we cannot hope for much more improvement.

The primary consideration when purchasing a vehicle is cost. When EVs are cheaper than all alternatives, what will happen to the alternatives?

Further Improvements over ICE

Decreases in purchase price are not the sole reason EVs will succeed. Operating costs, safety, and other peripheral improvements contribute as well.

It’s no secret EVs have lower operating costs than ICE vehicles. Electricity costs vs. gas and less maintenance lead to overall lower operating costs. However, depreciation is a factor that can cause the total cost of ownership to increase, but this is a short term problem. As EVs gain market share due to the other factors EV-specific depreciation will cease being an issue.

The EV architecture is also inherently safer than ICE vehicles for several reasons. The battery pack moves the center of mass lower which lowers the probability of roll-over, the lack of an engine leads to a larger crumple zone, and the lack of combustion lower probability of fire.

Finally, there are peripheral improvements that effect EVs more than ICE cars. The direct to consumer model leads to a better customer experience and a streamlined purchasing process. This is far more common in the EV space due to the higher risk tolerance and ability to innovate of EV companies. The lack of a dealership also allows for a more direct relationship between the manufacturer and the consumer. This allows for better customer service and a better overall experience. The ease of charging and at home is an improvement for the majority of consumers along with the smoother and quieter ride. Furthermore, 95% of trips are under 30 miles. For these daily trips, charging at home becomes an amazing feature as you never have to spend time refueling your vehicle.

Hybrids & Hydrogen Won’t Succeed Against EVs

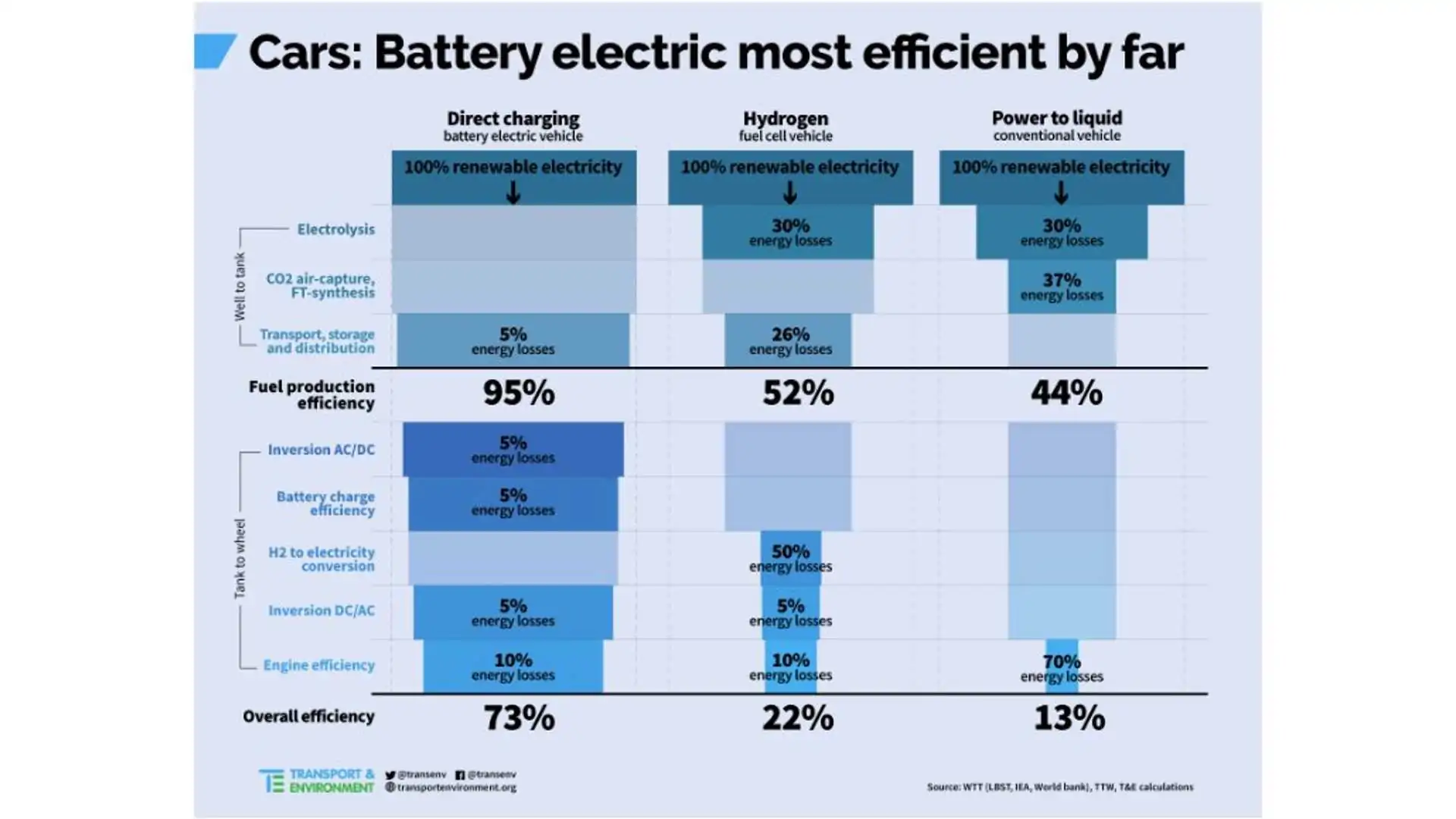

Many products that make sense from an environmental perspective do not work economically when compared to electric vehicles. This can be seen with hybrid and hydrogen vehicles.

Hybrids and Hydrogen cars do not fully benefit from the declining costs of EV technology as these designs are forced to contend with legacy and/or high-cost technology.

Again, this is mainly an economics problem and an engineering or consumer mindset may lead to incorrect conclusions.

The added range and speed of refilling of a Hydrogen vehicle is not enough to offset the cost of the Hydrogen infrastructure. The appeal of Hydrogen cars is relative to the future - mainly economic - appeal of EVs. Furthermore, with the declining costs and mass of batteries, the range and recharging speed of EVs will reach a point where the advantages of Hydrogen are negligible. To a certain extend this has already occured.

Hybrids will not be able to compete with EVs in the long term due to the static costs of the ICE powertrain, the lower maintenance cost of EVs, and decline in purchase price of EVs. Hybrids and EVs may be equal in carbon footprint, but vehicles are not purchases because of how many turtles are saved, vehcile are purchased mainly based on price.

Heavy Vehicles

The sources of decreasing cost in personally-owned EVs have vastly greater effects on heavy vehicles. Because of the increased usage of heavy vehicles and the operator’s lack of consumer preferences, it is very easy to predict the success of EVs in this segment. Comparing ICE and EV semi-trucks illustrates this.

| Cost of ICE Semi-Trucks | |

|---|---|

| Driver | $100k / Year |

| Maintenance | $10k / Year |

| Fuel: 200,000km / 10km/gal * $3.5/gal | $70k / Year |

| Other | $5k / Year |

| Max Payload | 65,000 lb |

| Annual Total | $185k / Year |

| Annual Cost / Max Payload | $2.85 |

| Cost of EV Semi-Trucks | |

|---|---|

| Driver | $100k / Year |

| Maintenance | $5k / Year |

| Fuel: 200,000km * 1.1 kWh/km * $0.16/kWh | $35k / Year |

| Other | $5k / Year |

| Max Payload | 55,000 lb |

| Annual Total | $145k / Year |

| Annual Cost / Max Payload | $2.64 |

Based on the numbers I used, EV semi-trucks are currently ~7% cheaper than ICE semis when operating at maximum payload. I will use this 7% number to illustrate my points throughout this section as it is directionally correct and EVs will become cheaper over time. You can substitute your own numbers, but understanding the implications of future cost declines is the most important point.

An EV Semi saves the operator $40k (22%) per year while only decreasing payload by 10,000lb (15%). A 7% cost reduction may appear very marginal, but for large companies like Amazon and Pepsi this can save hundreds of millions of dollars per year, enough to warrant significant up-front investment in Amazon’s case.

Electric semi-trucks must not exceed 82,000lb in the US. This maximum is 2,000lb more than ICE as an incentive to EV semi-manufacturers. The Tesla Semi is ~10,000lb heavier than an equivalent ICE semi and even with this drawback, operating costs are lower than that of an equivalent ICE semi. When a semi-truck is not operating at maximum load the cost improvements of EVs are even more pronounced. So, semis that often transport light loads (volume-constrained) can save more than 7% if they use EV instead of ICE.

The average cost of a semi-truck is ~$150,000. The Tesla Semi costs $150,000 for the 300-mile model and $180,000 for the 500-mile model. This is already near cost parody with ICE Semis, but EV semi-manufacturers are not done yet. Because of the decreasing costs of batteries outlined in earlier sections, EV Semis will soon be cheaper than ICE equivalents.

To illustrate the potential future cost declines in EV semis, the Tesla Semi’s battery is ~900kWh. At current EV battery pack costs (not cell costs): 900kWh * $128/kWh = $115,200. Presumably, Tesla is already below this cost with the 4680 cells. If battery costs decline 80% in the next 10 years (page 8), the cost to produce an electric semi may fall by more than 2x. Even if you’re less optimistic, the trend is clear.

Not only the cost to produce electric semis is decreasing, but also fuel costs. The average price of electricity in the US is $0.16/kWh. Current solar installations can produce electricity for 6-8 cents per kWh. As sustainable energy generation sources further decrease in cost and increase in production, electricity prices will fall. Furthermore, if trucks are charged mainly in the day you can forego the need for batteries. Many of industrial applications can make use of this to save costs in a future Solar, Wind, and Battery energy grid (ctrl-f “battery” to find the relevent sections).

For niche applications, electric semis are not yet ready to compete with ICE semis. In some metro areas electricity prices are absurdly high. When electricity prices are 3x the national average, electric semis are not economical. For example, if a semi’s job is to offload containers from a port in a metro area, it is not ideal to use an EV semi in a poorly managed city with high electricity prices. Also, if a semi must travel >500 miles without stopping for 30 minutes to charge or if it is carrying an areodynamically inefficient payload, EV semis are not yet competitive with ICE.

The range of EV semis is not a major concern. Truck drivers drive 605-650 miles per day on average. This may require 2-3 stops to charge. If an efficient route is used, this may only delay the delivery by ~1 hour. Regardless, truck drivers legally must stop to rest and in this time the truck can be charged. Significant capital investment is required to construct the chargers, but this is a profitable business model, so it is only a matter of time before the chargers are constructed.

Semi-trucks are not the only heavy vehicles that will transition to EVs as vehicles that often travel short trips are ripe for transition to EVs. Firetrucks often only serve their local area, no more than a 10km radius. Furthermore, Buses can charge in 5-10 minutes depending on route length and battery size, short enough to charge while waiting for passengers at a home station.

Other Concerns with EVs

The largest concerns among consumers about EVs - aside from price - are range and charging time. Modern battery packs can charge from 20% to 80% in 30 minutes, and V3 Super Chargers can charge 1000 miles per hour at peak. Furthermore, 95% of trips are under 30 miles. For these short daily trips, home charging can suffice. Even a regular 110V outlet can serve the majority of use cases, though a larger home EV charger is necessary for most people ($495 from Tesla).

Because of the fast charging time of modern EV chargers, charging during road trips is not a concern. If you buy a Tesla, it will automatically route you to chargers along your trip. If you have to drive 1000 miles across the desert non-stop to escape terrorists, gas may be ideal for you. However, if you stop every few hours during roadtrips to eat or go to the bathroom in a gas car, you won’t have trouble with an EV. EV faster charging companies are begining to servive the niche where they are necessary. There are interesting engineering considerations here like using an on-site battery pack to charge during peak demand.

Towing is a concern for many pickup-truck owners. In worst case condititons - cold weather, areodynamically inefficient payload - the range of your EV may be 3x lower than usual. The range of pickup trucks must be higher to accomodate this use case. The decreasing costs of batteries will allow EVs to get higher range for lower cost, but this will likely always be a weak spot for EVs. As mentioned above, it is very rare for tips to exceed 100 miles while towing. That 1% of uncles from Alabama will continue using their ICE pickups for this use case.

Modern battery packs last millions of miles. Battery health is only a concern among the absolute low-end of EVs made with bad batteries and battery lifespan is improving with each successive generation.

The grid will be able to support a fully electric vehicle fleet. If every new car sold in the US became electric tomorrow, the grid would have to grow by ~1% per year. 15,800,000 cars * 12,000 km/year * 4km/kWh = 48 billion kWh / year. The US electrical grid generated 4,231 billion kWh in 2022, growing it 48 billion kWh per year is not insurmountable. Furthermore, the lower costs of sustainable electricity generation will allow for more rapid expansion. We are entering a new paradigm of energy generation and consumption with Solar, Wind, and Batteries.

Autonomous Revolution

The Value of Autonomous Driving

Above I detailed the two primary methods I used for analysing the value of autonomous driving. Considering the cost per hour or the cost per kilometer. The cost per hour method is more useful for selling self driving software to consumers, while the cost per kilometer method is more useful for analysing ride hailing. This section focuses on selling self driving software to consumers so we will consider cost per hour. Later, the Ridehailing section will focus on cost per kilometer.

First, cost per hour. FSD Beta currently costs $200/Month. Assuming you commute 20 hours per month (1 hour per work day), this is $10 / hour. There are two components to how enticing saving one hour of driving is to a consumer: the value of the regained time and the value of alleviating the stress of driving. A low-income teenager’s time is not very valuable and they may like driving, so the value of FSD is low. A corporate middleman’s time is more valuable and they may feel souless after commuting for a decade, making self driving car software very valuable.

Your car driving itself is a much better experience than driving manually. How much better it is depends on the time since you got your license. The most high-end experience of transportation is a luxury car with a chauffer. Self driving software allows for the chauffer element to reach every consumer.

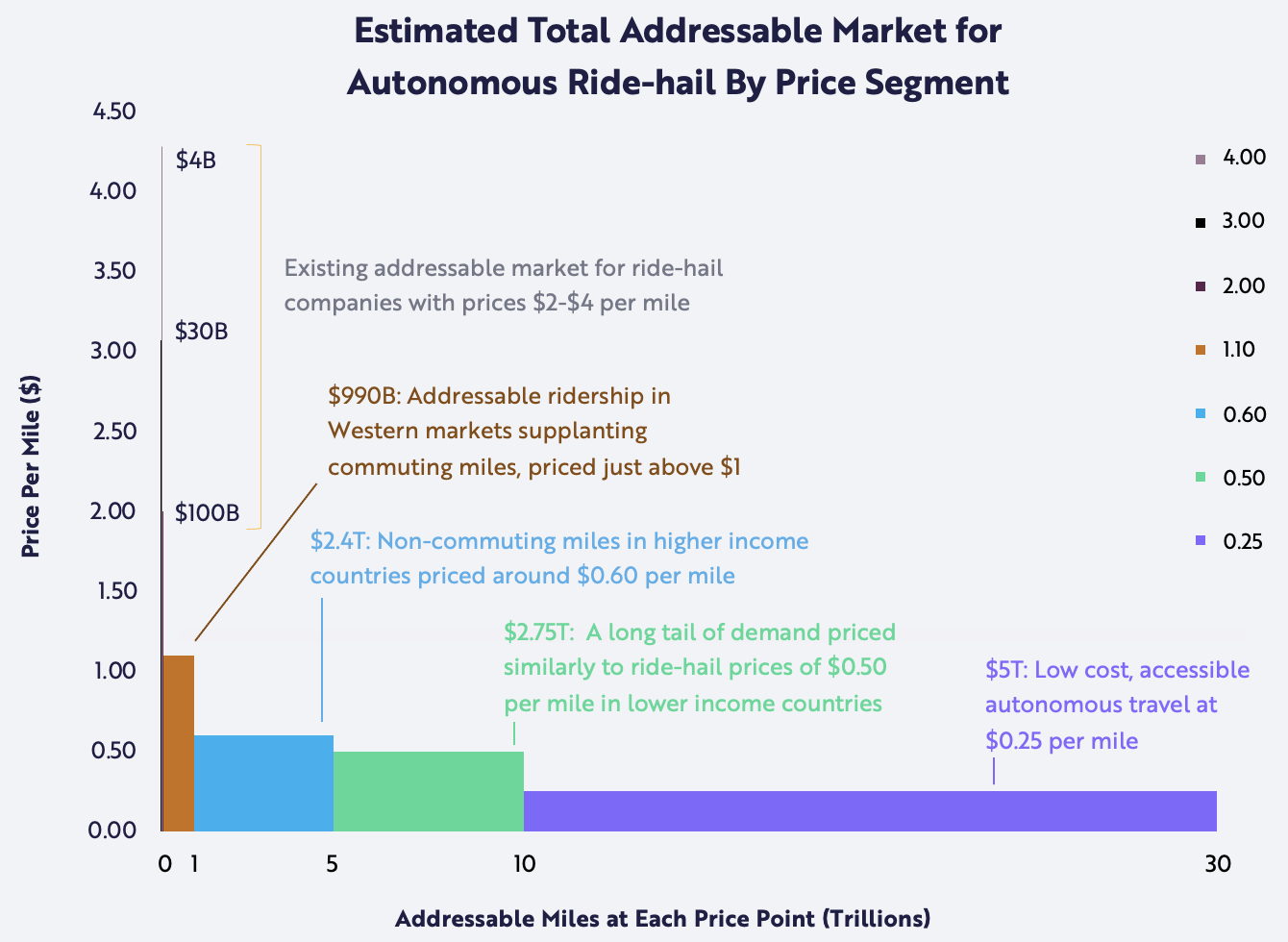

The TAM of self driving software can be expressed on an exponential graph. A linear decrease in price leads to an exponential increase in potential customers. This can be seen in many industries ranging from the begining of the industrial revolution to the present. For example mobile internet, phones, colour TVs, radios, sewing machines, etc.

The ability to linearly decrease cost while exponentailly increasing customers allows for a higher overall profit while each subscription costs less. Creating software to drive a car is mainly an R&D project and if you are selling it directly to customers there you can take advantage of profitable device sales. The effect of this is that as total number of customers increases, R&D cost is amortized over more customers which leads to a lower cost per customer. This is the process through which the cost of self driving car software will come down in the future.

How Self Driving Will Be Achieved

Creating software that drives a car is an AI problem. It benefits from general advances in AI and the exponential progress of AI. This means you must think about self driving cars the way you think about AI, it is exponentially advancing. Would you have laughed at GPT-2 the same way people did when FSD thought the setting sun was a red light?

Everyone hoping to understand AI must read The Bitter Lesson. Over the last couple of years with Tesla switching to an end-to-end neural net approach and the failure of many self driving companies, it has become clear that feature engineering is not the proper approach to solving this problem. “The biggest lesson that can be read from 70 years of AI research is that general methods that leverage computation are ultimately the most effective, and by a large margin.” - Rich Sutton, The Bitter Lesson. Just look at the growth of AI and extrapolate into the future. But remember: it’ll never make hands, artists are safe.

The requirements of training end-to-end self driving car systems are massive amounts of useful data, massive amounts of compute, and very intelligent engineers. Tesla has the most of all of these and is most likely to succeed at creating a self-driving system first. Once other systems reach maturity and have similar capabilities to FSD they will be able to compete on cost. However, the first mover advantage will allow Tesla to partner with OEMs and install FSD in vehicles during production. Even in the case of Comma AI - a system that can be installed in any vehicle - they will be fighting an uphill battle.

Pursuing a strategy like Waymo’s is very inefficient because it does not leveraging the exponential growth of compute and data. This strategy will take more resources and time to achieve the same result, by which time the competition will have already been operating at scale for years and will be well ahead. Self driving AI systems that do not leverage exponential advances in AI may succeed in the future in the same way that I could create a Chess AI that beats Magnus Carlson through sheer brute force search (depending on time control), but it would be a waste of time & money and Stockfish would easily out compete it. Assuming self driving car systems reach a plateau where they are perfect, an inefficient system will still not be able to compete due to increased costs. For example, Tesla is paid ~$20,000 for every vehicle (All of which can train and run FSD) while Waymo is paid around negative $150,000 to add a vehicle to its network.

How Much Will It Cost?

There are two components to the cost of a self driving car: the cost of hardware and amortizing development cost.

A Comma 3X costs $1250, Tesla’s FSD Hardware is rumored costs a similar amount (more parts but at higher scale in a manufacturing focused organization). This cost must either be worked into the purchase price of the device/vehicle or factored into the cost of a subscription.

The development cost must also be factored in for the business to be net profitable and this will become a smaller percentage as the number of customers increases. Tesla currently spends a few billion per year on AI, at 2 million cars per year this is ~$1000 per car. Overall, it appears that the cost of development is increasing at a slower rate than the number of cars sold, so the cost per car is decreasing for Tesla. Furthermore, once true self driving is achieved, the number of customers explodes.

The hardware cost is similar to many consumer electronics devices that are sold today. Relative to a vehicle, hardware cost is negligible.

The subscription cost is much more important to consider both as a consumer and as the provider. The subscription will be the majority of the cost for the consumer. Subscriptions are 100% gross margin while hardware is far less than 100%, for this reason the subscription will be the primary source of profit for the company providing the self driving software.

Like all other subscriptions, the cost will even out when the area under the curve of customer count vs. subscription cost maxes out. I haven’t found a useful enough public dataset to predict where the subscription cost will lie, but judging from other subscriptions, it could be between $50-$300/month. Tesla recently decreased the cost of FSD Beta to $100/Month.

First Mover Advantage

In the short term, the first few years after a company creates reliable self driving car software they will have a significant advantage over the competition. This first mover advantage stems from the exponential nature of AI development and difficulty of driving. Self driving is an AI problem, so it will advance exponentially. If one company has a head start, their exponential will be significant ahead of the competition. However, the first mover advantage will not last forever because the advantage of one system over another will level out as the systems approach perfect driving. For example, if one system is 99.99999% safe and the other only 99.9999%, the difference is negligible. Aside from deceptive marketing “You’re 10x more likely to die in a competitor’s car!”, there will be no sigficant differences between the two systems.

The convergence between self driving systems is technical and the first-mover advantage stems from this. The lock-in effect will mainly be due to the difficultly of switching between different providers. This assumes technological convergence has occured. In the mean time, certain competitors will have pricing power over each other. Partnerships with OEMs will be an early indicator of a first mover advantage - of course when the software is mature enough, not before.

If devices are as easy to install and swap like a Comma 3, the effect of lock-in is diminished but remains in the cost of switching providers. You can imagine an OEM which has constructed their manufacturing lines around Tesla’s FSD Hardware will be aprehensive about switching to Comma AI.

Ride Hailing Revolution

Consider this: https://x.com/aleximm/status/1867257473671082356

I started writing this blog post 293 days ago and working on it here and there over this time. I have less time than ever studying engineering at UBC, so this section will give directional analysis of where this market will go. In the future, quantative analysis is required.

This isn’t a quantitative analysis, but rather thinking directionally.

THINK DIRECTIONALLY

- Cost per KM comparison to public transit ($0.1 - $0.3/km)

- Rough cost estimate: $0.1/km

- Potentially cheaper than public transit, especially for subsized public transit

- Higher efficiency than personal car and taxis

- Fleet advantage through economies of scale, but not too important

- Vehicle Market will shink (minimum number at worst rush hour)

- Not everyone will run their car as a robotaxi, market saturation. In the future, this will be a relatively low margin market per km due to competition.

- Amortize car cost

Structure:

- Why it’s a better service

- Potential cost (Amoritzation, Insurance, maintenance, cleaning, charging, etc.) + Higher efficiency than taxis

- Implications for public transit and current ride hailing services

- Implications for personal car ownership and the vehicle market

- Fleet advantage vs. personal car robotaxis

Summary

- Use economics to understand the future.

EVs:

- Declining manufacturing costs and improving technology

- Hydrogen, Hybrids, and ICE won’t compete on economics

- Think directionally on trucks

Autonomy:

- Tons of value, what do you price it at?

- The Bitter Lesson, Tesla will win

Ride Hailing:

- Cheaper than personal car ownership and maybe public transit

- Will take immense market share

- The vehicle market will shrink

- Amazing service, the future looks bright