Stoke's Nova is a Perfectly Sized Rocket

At first glance, Stoke’s Nova appears to be an immensely exciting R&D project without much commercial appeal. In a world where the most successful rocket is a 20-ton class partially reusable launch vehicle, it is difficult to see exactly how such a comparatively small rocket will compete. Data is the answer to all your problems, so I’ve answered all my questions with my dataset (Based on Jonathan Mcdowell’s public data, Gunter’s Space Page, and others) on successful western orbital launches from 2018-2023 inclusive and will convey all insights in this blog post. My primary goal is to examine Nova from a demand perspective.

Stoke’s Nova rocket is perfectly sized to compete for existing satellite launches and future constellations. It can compete for LEO satellite launches as the average mass of customer payloads on Falcon 9 is 3.7 tons (ex. Dragon). Full reusability will allow it to compete against Electon and launch constellations even with its 3t-7t LEO capacity. The launch cost must be several times lower than competitors and reusability allows for this. Finally, the fully reusable architecture lends itself to becoming a cargo/crew capsule while refilling in orbit to address high energy orbits and potentially Moon/Mars landings.

Full Reusability Makes Constellations Addressable

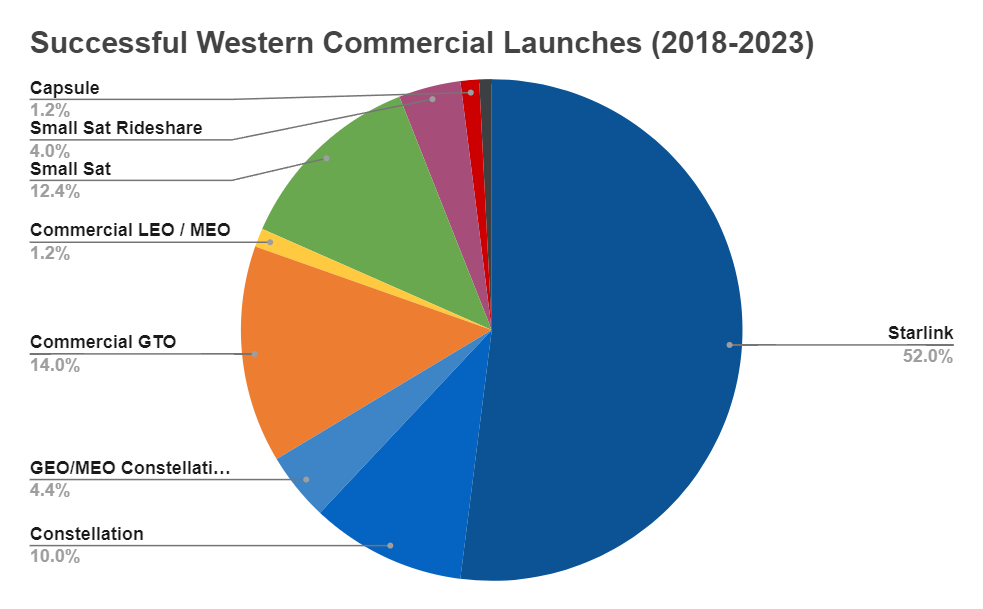

Through following current trends in the launch market it is clear that launching constellations is the market that almost all new rockets should be optimized for. 67% of commercial launches in the last 6 years were for constellations. 80% of these launches were Starlink while the remaining is comprised mainly of Iridium and OneWeb. With numerous upcoming constellations - mainly Kuiper - it is clear this market will experience much more rapid growth than other payload types.

Excluding Starlink, the market for commercial launches is shared in equal thirds between Constellations, GEO Communications Satellites, and Small Satellite launches. Legacy GEO Communications satellites are a fairly static market and have been for ~20 years at around 10 launches per year. Small satellites are experiencing exponential growth, but the TAM for rideshare missions is relatively low. This leaves constellations as the massive market that is exponentially growing.

The primary considerations behind launching constellations are responsiveness and cost per launch per satellite. Constellations can be launched on rockets of almost any size because they are made up of a large number of relatively small satellites. To illustrate this, a 20-ton class medium-lift launch vehicle is not the only vehicle type capable of launching constellations because a 5-ton class rocket can be competitive if the cost is 4x less and has 4x higher cadence. Furthermore, the requirement for an increased number of launches potentially gives advantages in responsiveness.

Stoke’s Nova is rumored to have a 3-ton LEO capacity when reused, 5-tons when the booster is reused, and 7-tons when fully expended. At this scale, to be competitive with Falcon 9 it must be ~6x cheaper per launch which would cost $10M for the customer or ~$2.5M internal marginal launch cost. As we’ve seen with Falcon 9, reusability has dramatically decreased launch costs to the point where the majority of the cost of a rocket is no longer in the first stage. Second-stage reusability will drive down costs even further and a small launch on the scale of Stoke’s Nova is well suited to achieving a high launch cadence which will accelerate the process of decreasing costs.

Nova can Launch Most Payloads

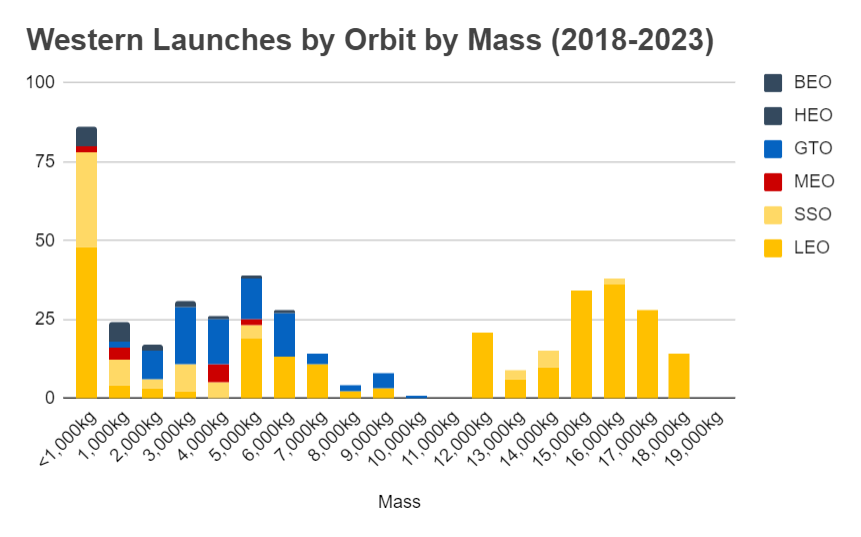

Launching legacy geostationary communications satellites has very different considerations from launching constellations. These launches require immense mass to GTO capability and prefer high-energy optimized architectures like Ariane 5 or Vulcan. However, ~60% of the commercial GEO satellites launched in the last 6 years were under 5 tons. Because refilling in orbit is planned for Nova, it will be able to put its entire LEO capacity directly in a geostationary orbit and potentially return the second stage (Assuming 6000m/s+ delta-v in the upper stage similar to Starship & <3-ton payload). Because the vehicle is fully reusable - at <3-ton payloads - this may cost less than a dedicated Falcon 9 launch.

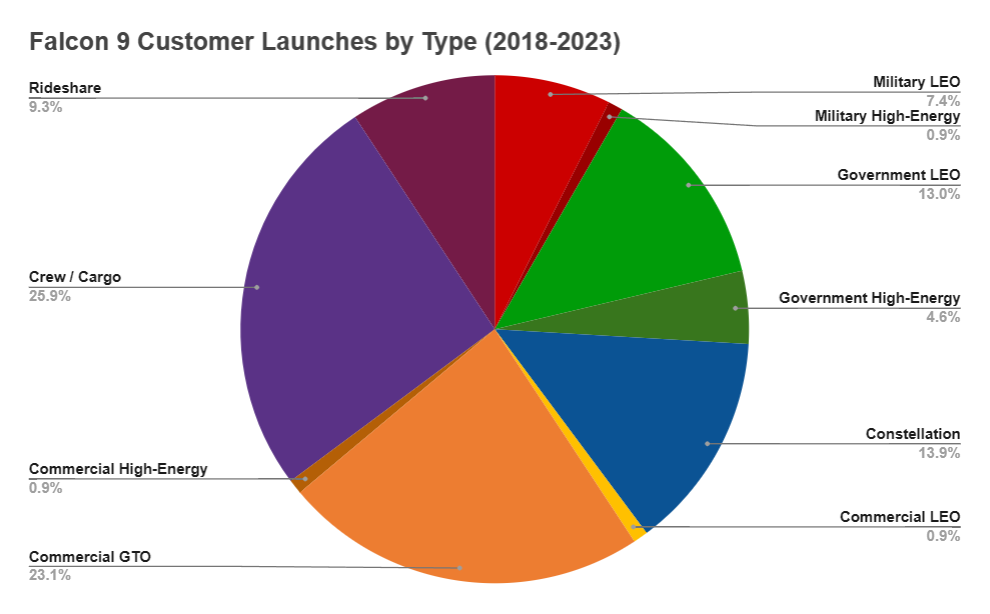

The average mass of Falcon 9 customer LEO launches excluding Dragon is 3.7 tons. Between 2018 and 2023 inclusive, 32 of these launches occurred and only 4 of them were over 5 tons. This means Nova could have launched 28 of the previous 32 Falcon 9 customer launches while reusing the booster and slightly less if reusing the upper stage as well. This assumes there were no further considerations such as payload volume. Because Falcon 9 is oversized for the majority of LEO customer payloads, Nova is well-positioned to compete in this market.

Small satellite rideshare missions are well suited for Nova given their low mass requirements and flexibility. For example, SpaceX Transporter missions are often below 5 tons, another example of Falcon 9 being oversized for customer payloads. The limiting factor in Nova being able to launch these missions may be payload volume because Nova’s payload fairing is smaller than Falcon 9’s. Regardless, this is solved by launching fewer satellites at once. Rideshare missions are flexible enough that they can launch on nearly any vehicle and the potential for extremely low cost with Nova makes it well-suited for these launches.

It’s not just rideshare missions that Nova can address, but given potentially extremely low costs, it could be economical to conduct dedicated launches for small satellites. Stoke will have to decrease costs below where Electron is today - ~$8M - and increase cadence. If second-stage reuse is achieved, Electron-level costs are possible and because Nova has many more market segments available than Electron, a higher cadence can be achieved.

All 4 of the Falcon 9 LEO customer launches that exceeded Nova’s 5-ton booster-reuse payload capacity were for the US Military. There were two NROL launches and two SDA launches. Because of the classified nature of these payloads, their exact mass is unknown, so some of them may be within Nova’s 5-ton payload capacity. Even so, to launch these payloads Nova would have to be certified by the US Military to launch classified payloads under NSSL Lane 2 which is unlikely given competition from SpaceX and ULA. NSSL Lane 1 payload are of lower mass and lower energy orbits which Nova will be able to compete for.

NSSL’s phase 2 target orbits can illustrate the advantage of orbital refilling. Nova may be able to achieve all but one of the NSSL Phase 2 target orbits if the vehicle used the 7-ton fully expendable LEO capacity. These orbits are mainly high-energy and require 4-7 tons of payload capacity. For example, the GEO 2 target orbit requires 6.6 tons direct to GEO and MEO Direct 1 requires 5.3 tons direct to an 18,200km orbit of Earth. The only required orbit Nova can’t achieve is Polar 2 which requires 17 tons to a 830 km polar orbit of Earth. This shows that in-space refilling is a feature that opens up a lot of capability and how Nova will be competitive for NSSL Phase 3 Lane 1 payloads.

Crew / Cargo Capsule and Lunar Landing

Nova’s upper stage is a fully reusable orbital reentry vehicle capable of propulsive landing. Previous vehicles capable of orbital reentry have all carried crew or cargo and orbital vehicles capable of propulsive landing have all been Moon/Mars landers.

In Stoke Space’s promotional video 4 months ago they teased in-orbit refilling and Moon landings. As mentioned above, in-orbit refilling allows them to increase payload capacity beyond low-earth orbit which also makes it possible to achieve a lunar landing. Using low earth orbit as a starting point, a lunar landing requires ~5,700 m/s of delta-v. If Nova’s upper stage has a similar delta-v to Starship (6000m/s), this is possible with a full 5-ton payload. Even if delta-v is lower than 6000m/s or significant extra mass is required to achieve a lunar landing, the payload capacity to the lunar surface will be greater than a ton. This is a higher payload capacity than the largest Commercial Lunar Payload Services lander - Astrobotic’s Griffin - which is capable of delivering 625kg to the lunar surface. A Nova-based lunar lander could deliver more payload to the Lunar surface for a lower overall cost than the existing CLPS landers.

Lunar landings of lower cost and higher reliability are made possible by testing the landing system on Earth dozens or hundreds of times before attempting a Lunar landing. Engines and maneuvering systems will be tested many times before a lunar landing which makes a failure during landing far less likely. For example, failures like Peregrine, Luna 25, or Beresheet would not have occurred on a sufficiently tested vehicle. Lunar-specific features cannot be tested on Earth such as communications or landing software and these are among the greatest causes for failure. A lunar landing with Nova remains a significant technological challenge, but a vehicle tested on Earth or in Earth orbit hundreds of times has a far higher chance of success and can be cheaper.

Nova is an undersized rocket for launching crew. For example, Soyuz is one of the small crew capsules currently flying and it weighs 7 tons. This is beyond Nova’s 5-ton partially-reusable LEO capacity and makes it very difficult to create a crew capsule even if it is integrated into an existing spacecraft with maneuvering capabilities. A Cargo Capsule is more reasonable, but it may be unlikely that there will be sufficient demand for Stoke Space to pursue this. In his interview with NASASpaceflight, Andy Lapsa - Stoke Space CEO and cofounder - was asked about crew rating Nova and said this: “I actually expect that we’ll see a bimodal distribution in the optimal size of the vehicles. One of them is designed for satellites and one of them is probably bigger designed for humans with life [support] systems.”

Small Size if a Feature

The fully reusable architecture allows for a high flight rate which can bring down the cost per launch and allows for rapid iteration.

Flight rate is one of the primary factors behind falling launch costs apart from vehicle architecture. Launching many multiples more than your competitors with a smaller fully-reusable vehicle allows for an accelerated process of lowering costs. Contrast this with Neutron, which will likely launch less than Falcon 9 with a second stage of similar complexity. This suggests it will be much harder for Rocket Lab than Stoke to compete with the Falcon 9.

Launching constellations would provide an excellent opportunity for Stoke as they could substantially increase launch cadence as Starlink did for Falcon 9. Constellation satellites are payloads that can accept more risk than other more expensive, one-off payloads. This means they can be launched on riskier life-leading boosters and upper stages. For several years, the life-leading Falcon 9 boosters only launched Starlink satellites. After years of testing and iteration SpaceX’s customers became comfortable with launching on these boosters. SpaceX’s current life-leading booster, B1060, recently launched the Odysseus IM-1 lunar landing mission on its 18th flight.

SpaceX iterated on Falcon 9’s design for years and refined it through the process of launching Starlink satellites on life-leading boosters. Thus far, Stoke has embraced iteration and hardware-rich development through the development of Nova’s upper stage and the first stage engine. Launching constellations will allow Stoke to used the same spirit of iteration, hardware-rich development, and pushing hardware to its limits to refine the vehicle.

Competing Against Partially-Reusable Launch Vehicles

Vehicles like Nova are the perfect competition against partially reusable medium launch vehicles. This can be illustrated by seeing where Nova and Neutron will compete. First, the average mass of customer payloads on Falcon 9 is 3.7t (excluding Dragon). This is addressable both by Nova and Neutron. Second, the next largest market for Falcon 9 is GEO communications satellites. Neutron GTO capacity is supposedly to be 3-5 tons and because Nova is planned to be refilled in orbit, it will have a comparable GTO capacity to Neutron. Finally, both rockets will compete for launching constellations and because Nova is designed for full reusability, it can achieve an overall lower cost than Neutron.

Almost every payload that can be launched on Neutron can be launched on Nova. The major exception is LEO satellites that are >5 tons. This is a relatively small market as it is mostly US Military payloads that are launched by SpaceX and ULA. It is unlikely that Stoke or Neutron will be competitive in NSSL Lane 2 without more changes to NSSL policy, but they will be compete in NSSL Lane 1.

Heavy-lift rockets such as New Glenn and Terran R are much harder to compete against with a vehicle on the scale of Nova. Larger rockets can pursue unique missions and are better suited for heavy GEO satellites and massive constellations. For example, Nova could not compete for HLS as a vehicle on the scale of New Glenn or larger is required. Furthermore, for extremely large constellations such as Starlink or Kuiper, a larger rocket is better suited due to the sheer amount of satellites needed. Nova will need to launch many times a day to compete with these rockets on Starlink-sized constellations.

Competing Against Fully-Reusable Launch Vehicles

Stoke’s Nova is clearly an excellent architecture to compete against partially-reusable launch vehicles, but Nova’s position against larger fully and rapidly reusable launch vehicles is far less clear. In the next 10-20 years we will enter the paradigm of fully and rapidly reusable launch vehicles. It will not be just Starship and Nova, but every new rocket will be fully and rapidly reusable. When every major rocket is fully and rapidly reusable, Nova will not have all the benefits it will enjoy against partially reusable launch vehicles over the next ten years.

Large constellations will most likely be launched on large rockets. The sheer number of launches required to put the same mass into orbit compared to a heavy-lift reusable rocket makes it unlikely that a Nova-sized vehicle will be able to compete. For example, Nova would have to be 30x cheaper than Starship to be competitive. When rockets enter an airline-like model, cost per kilogram will become a more important factor and the larger scale of Starship will become more of a competitive advantage.

While large constellations will not be addressable by Nova, smaller constellations will be. All constellations require satellites to be launched into unique orbital planes to achieve proper coverage of the Earth. This can not be done on a single launch because of the immense fuel requirements to change orbital planes. On the scale of Starship, this means each launch may not carry enough satellites to be economical. For example, each Falcon 9 Iridium launch carried 10 satellites which weighed ~6.6t. This scale of constellation or smaller (Eg. Blacksky, Synspective, etc.) are well suited for a Nova-sized vehicle.

Aside from constellations, Nova may become the most economical small sat launcher. Its small size and full reusability will allow it to launch small satellites at a lower cost than any other vehicle, including Electron. Furthermore, it may not be economical to develop a smaller fully reusable small sat launcher due to the upfront development costs. A rocket designed for only small satellites will not be able to launch constellations or 1-5 ton satellites, which comprise the majority of the launch TAM. So, even if a smaller rocket is >50% cheaper per launch, it will take a very high number of flights to amortize the development cost. In 10-15 years Nova may begin launches more small satellites than any other vehicle.

In a world of fully and rapidly reusable rockets, Nova may be similar to Electron today. It will have a niche of payloads that are well suited for its size and cost. This includes small satellites, small constellations, and <5t satellites like those currently launching on Falcon 9.

Not Many Organizations Can Pursue Full Reusability

Current and upcoming rockets that are aiming to launch constellations are all partially reusable medium/heavy lift launch vehicles (excluding Starship, which is covered in the section above). A partially reusable rocket is the most reasonable thing for a slightly risk-averse company to do. For companies like Rocket Lab or ULA, it is very difficult to pursue a fully and rapidly reusable rocket because it is an unproven market and has never been done before which makes it a very hard sell to investors. This is especially true when you consider the development cost of such a program: ~$250M for Neutron vs. ~$5B for Starship.

It takes a level of audacity to push for such a program that will create its own market. SpaceX has done this again and again with Falcon 9, Starlink, and now with Starship & Mars. When existing stakeholders are not willing to take the risk, a more conservative approach must be taken that is less likely to succeed against a sufficiently capable competitor. We’ve seen this in the past with the SLS and other legacy launch companies like ULA.

A clear vision and path are required to pursue a fully and rapidly reusable rocket - along with immense amounts of capital. SpaceX achieved this under Elon Musk with his own fortune, NASA contracts, and venture capital. Stoke will follow a similar path, pursuing a goal that is decades away and beating the competition along the way because of this forward vision.

Conclusion & Predictions

A fully and rapidly reusable launch vehicle on the scale of Stoke’s Nova is perfectly sized to compete against existing and under-development partially reusable launch vehicles. It is well suited to launch constellations, LEO satellites, small & medium GEO satellites, dedicated small satellites, and small sat constellations. If full reusability is achieved with Nova, it will take significant market share over the next 5-10 years.

Over the next decade, we will start to enter the paradigm of fully and rapidly reusable rockets. These rockets will be able to launch all payloads at a lower cost than all existing vehicles and alleviate the current mass and volume limitations. The lower cost will allow for new markets to emerge and for a new paradigm of satellite design. K2 Space is already preparing for this by developing satellites that are very heavy and have a large volume. This increases launch costs but decreases the cost to build the satellite through using cheaper (but heavier) parts. There will come a point in the next 10-20 years when this becomes more economical than the current paradigm of satellite design, at which point a paradigm shift will occur.

Nova’s market this decade will be very different than the following decades. Before we firmly enter the paradigm of fully and rapidly reusable rockets and have payloads well suited to it, Nova will be able to compete against partially reusable rockets. After we enter this new paradigm, Nova will go the way of Electron and become more of a niche vehicle.

It is possible that Stoke will die brutally like Astra before it achieves low cost and high cadence with Nova. This would be immensely unfortunate because Nova is the coolest rocket ever developed, tied with Starship. However, even in such a depressing scenerio, a vehicle of similar scale to Nova will be developed in the future to adequately serve the <5t satellite market.