Visualizing Small Sat Constellation Tradeoffs with Charts

Tell me where I’m wrong or just give compliments here.

What Data Do We Need?

In my previous blog post I gained an intuitive understanding of the tradeoffs for the different methods of launching small sat constellations. This blog post is an exercise in quantifying and visualizing that understanding.

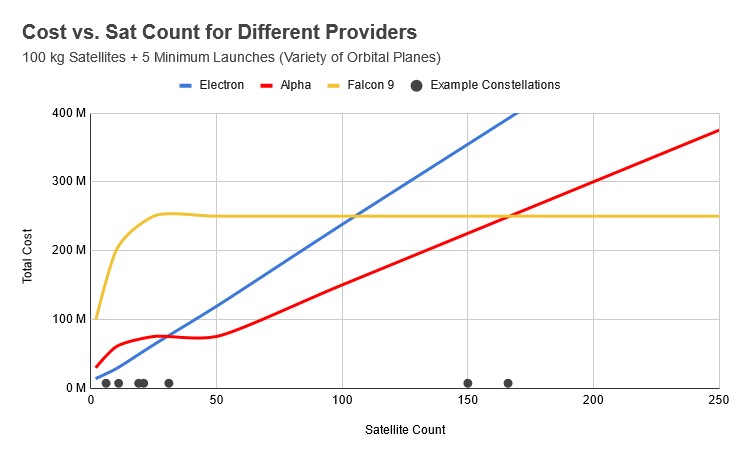

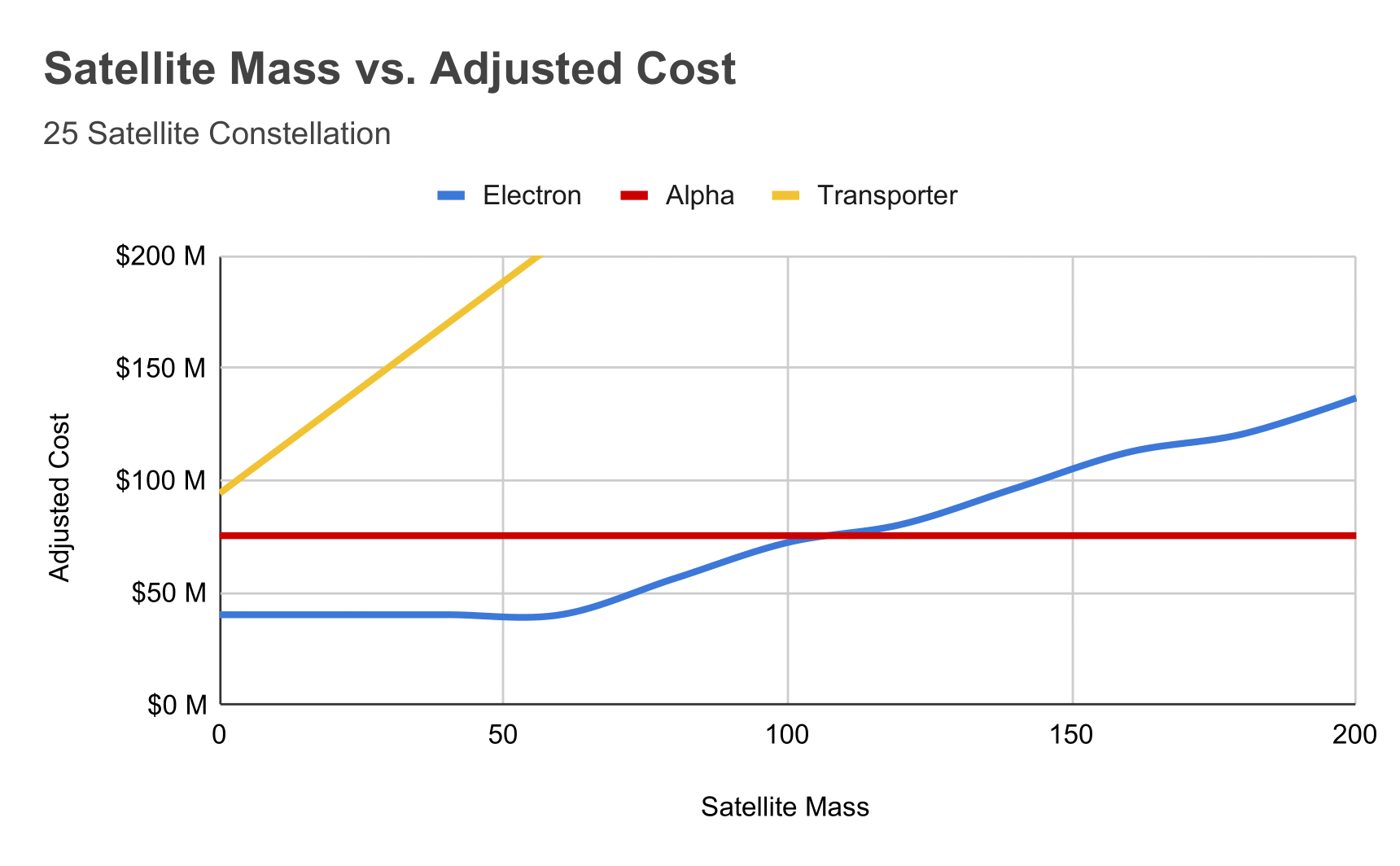

Yesterday I felt the need to create a visual representation of the tradeoff between small sat constellation operators choosing either Electron, Alpha, or Transporter. The result was the chart you see above. It clearly shows the size of constellation where Electron, Alpha, or Rideshare are the best options. However, this doesn’t take into account variables other than the raw cost, such as the suboptimal orbits of rideshare missions, true Transporter mission costs, or the low annual mass to orbit capability of Electron because of its “low” cadence coupled with it’s low payload capacity (Isn’t it great we get to live in a world in which 20 launches per year is “low” cadence, get on SpaceX’s level guys!).

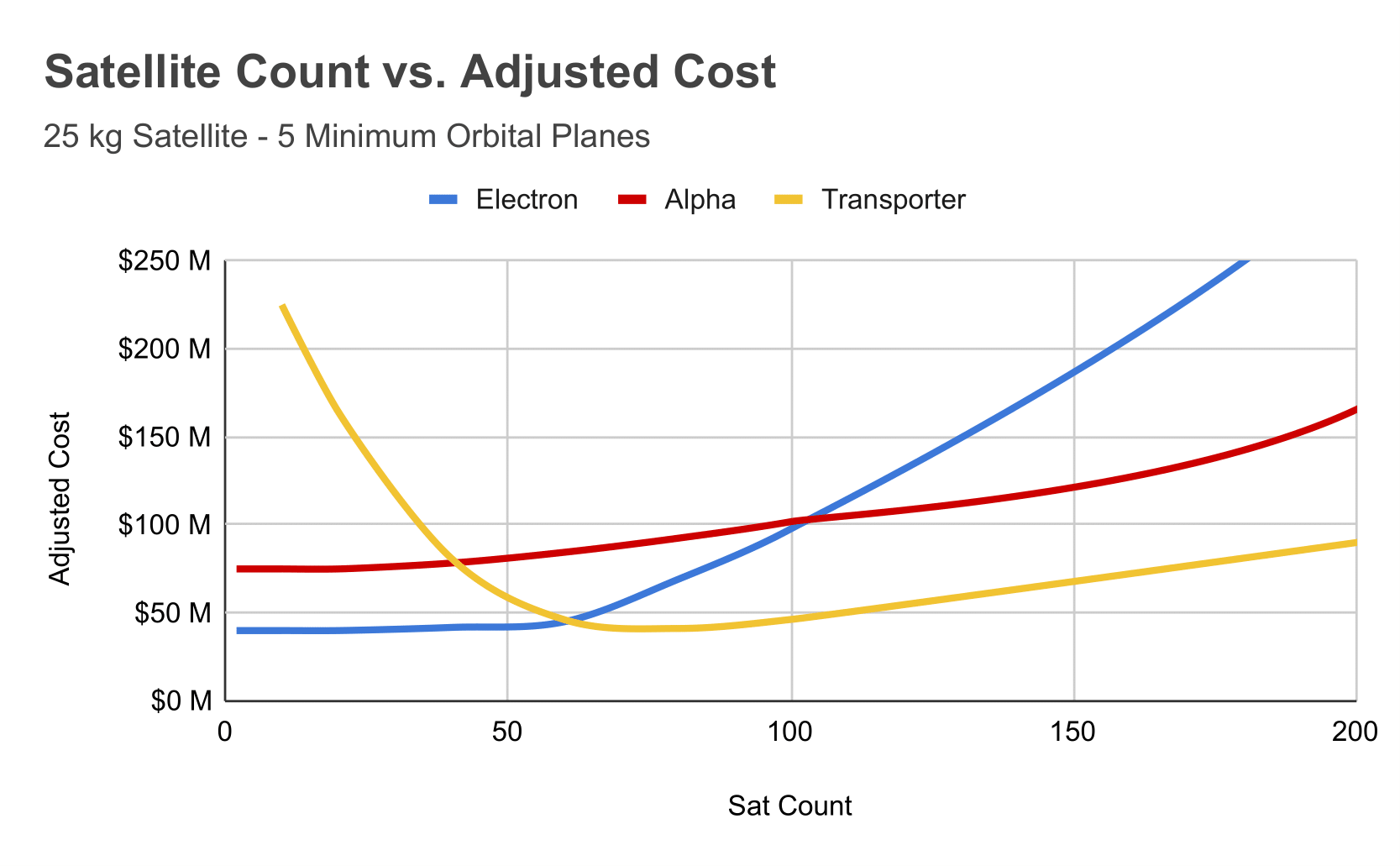

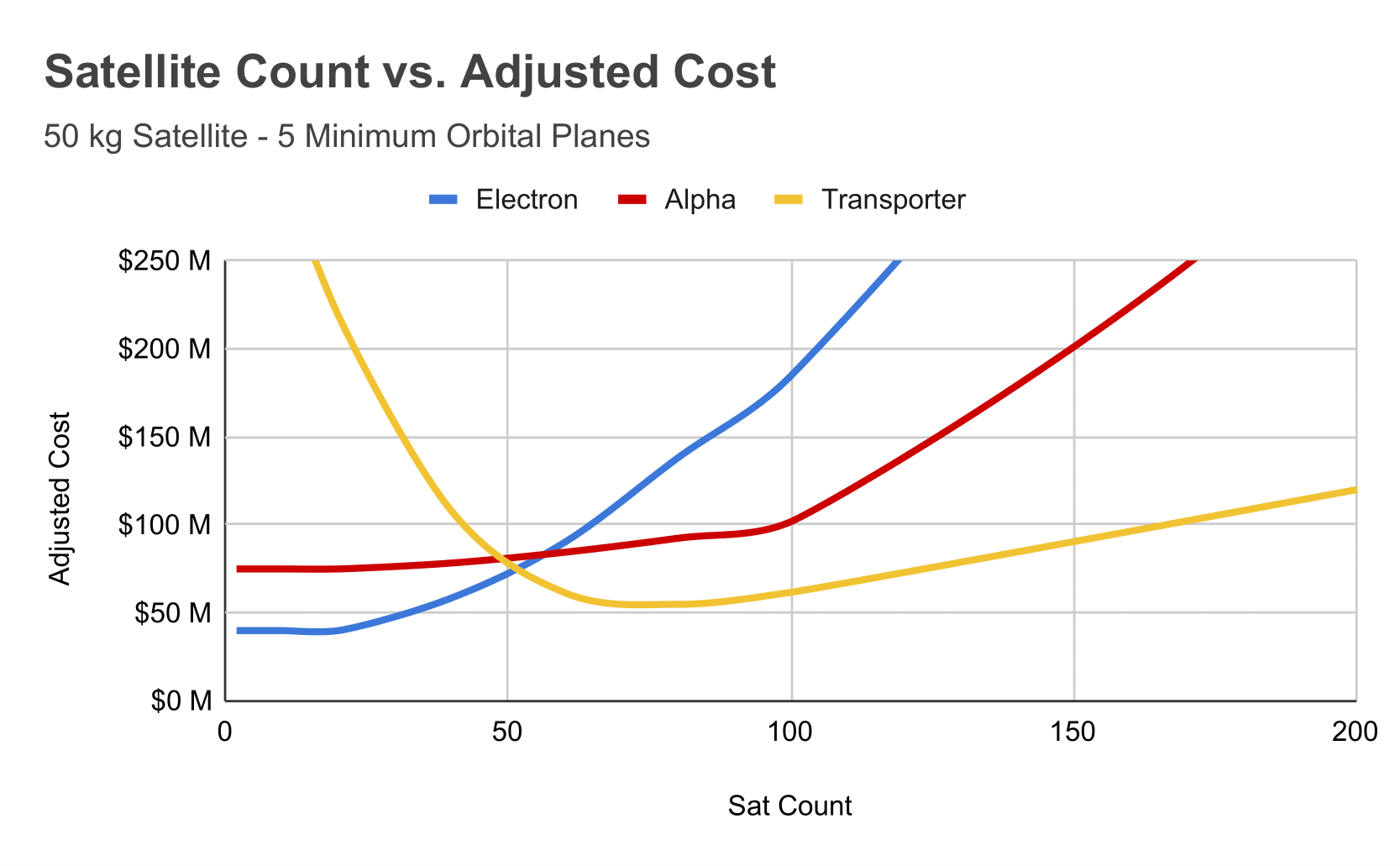

The solution to getting a more accurate picture of the tradeoffs is to abandon the true cost of launch and replace it with Adjusted Cost, a score that takes into account the issues laid out above. This is a simple concept, adjust the cost with a multiplier that uses the number of satellites as the input variable.

Orbit Detriment Multiplier (Rideshare): y = 85 * 2.71^(-0.08*sat count)

Cadence Detriment Multiplier (Dedicated): y = 0.0005(sat count - 20)^1.5

Orbit Detriment starts very high at 0 satellites and approaches zero as we near 100 satellites. This represents the fact that rideshare missions can’t be used to launch small constellations that require specific orbits like NASA Tropics, Capella, or BlackSky. It shifts the calculus towards dedicated launches for constellations with a low number of satellites.

Cadence Detriment begins at 20 and scales exponentially with the number of satellites, this takes into account the fact that Electron can’t launch 100 times on a whim. Furthermore, there is a minimum orbital plane input which sets the floor for the number of launches, this is required to get accurate data between Electron and Firefly’s Alpha at low satellite counts.

The result is several charts that are available here.

Insights

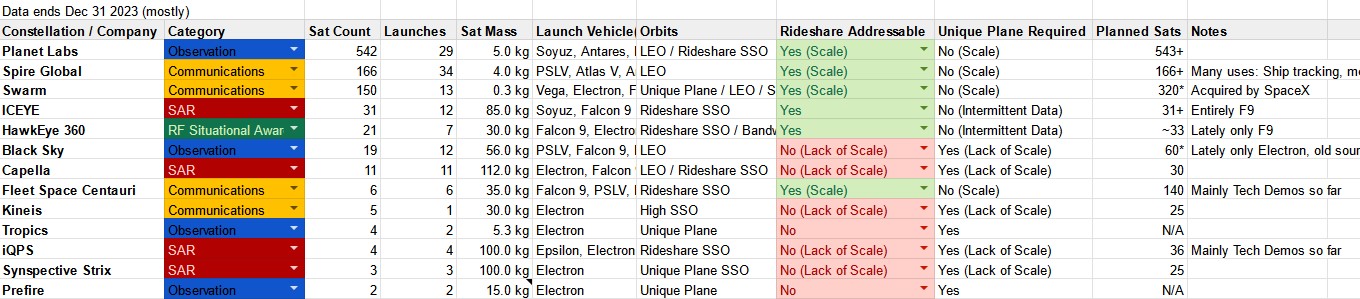

1. Most Constellations Below 100 Satellites Are Either 100kg or 50kg

This is essential data to understand the implications of the data below.

There are three primary categories of small satellite constellations.

- Constellations with >100 satellites, most satellites under 5kg (eg. PlanetLabs)

- 10-50 satellite constellations, mass between 30-112kg (eg. Capella)

- <10 satellite constellation, <15kg mass (eg. Tropics)

The most interesting data I’ve gathered from this exercise applies to the second category. These are constellations that fit into the category of either 25 or 50 satellites total with masses of either 50kg or 100kg. This is the biggest category of the market available to small sat launch providers.

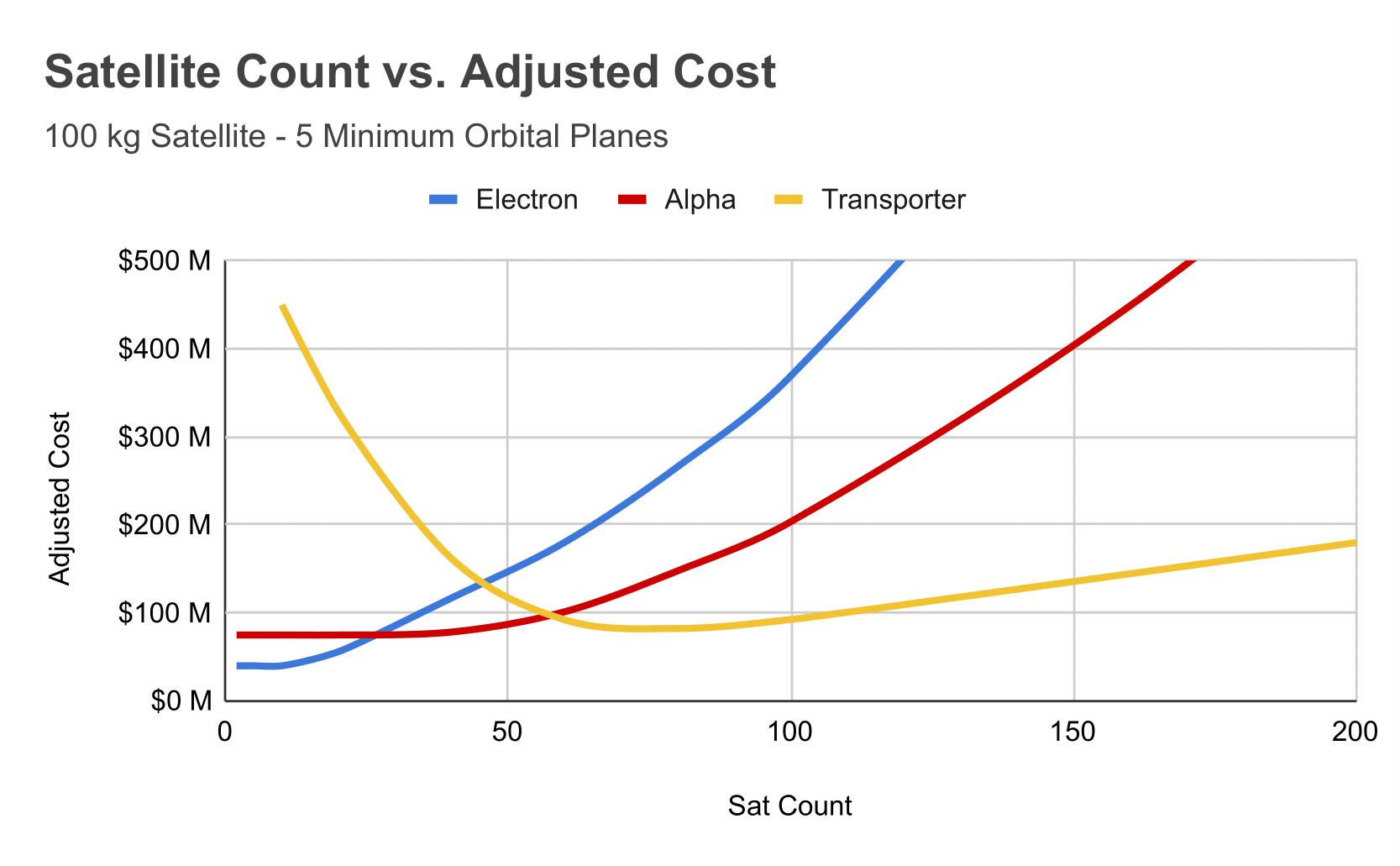

2. The Tradeoff Between Electron and Rideshare Occurs at ~50 Satellites

For constellations that don’t require the higher payload capacity of a 1-ton class launch vehicle like Firefly’s Alpha or ABL’s RS1, the options available are either Electron or Falcon 9 Transporter missions. These <50kg satellites are the most common size of constellations and the tradeoff between Electron and Rideshare occurs at ~50 satellites. There are no constellations at this 50 satellite size in my dataset because this is one of the gaps in the market. Go bigger and you end up with Planet Labs, go smaller and you end up with BlackSky at ~20 satellites. This conclusion is present in both the data of real constellations above and in the charts I’ve created.

It’s remarkable there’s enough satellite constellations that I can make statements like the one above. I was born at the perfect time to bask in the glory of the growth of commercial spaceflight.

3. At The Most Common Constellation Size, Alpha Is Optimal for 100kg+ satellites

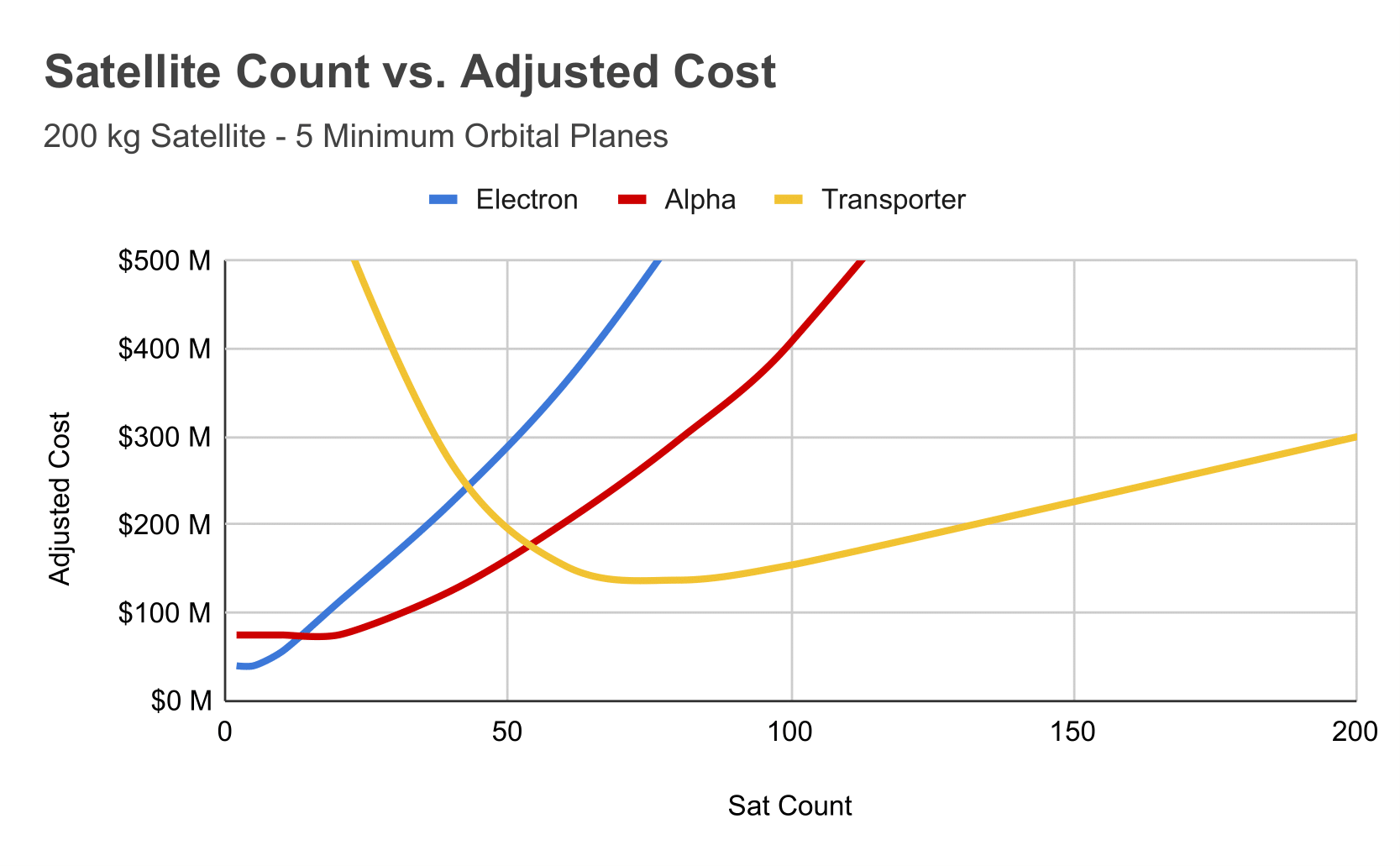

For most constellations (~25 satellites), Alpha is unable to properly compete with Electron because the satellites are not heavy enough to take advantage of the 1-ton payload capacity of Alpha. The higher payload capacity only starts to kick in with satellites that are over 100kg. For even heavier satellites (eg. 200kg+), Alpha provides a cheaper path to orbit than Electron, we may see some constellations pop up in this category in the future if Firefly or ABL demonstrate reliability. This is only true if the higher satellite mass prodives a significant enough advantage. For example, Earth Observation satellites seem to level out at around 100kg.

For larger constellations - eg. 50 satellites - the tradeoff shifts to lower mass satellites. This benefit extends until rideshare takes over at very large constellations, Eg. Swarm or Spire Global. The reason for this is that with a low number of orbital planes (I used 5 as a default value, we can debate this) a single 1-ton launch is more efficient than several 300kg Electron launches. Firefly’s Alpha has ~3x the payload capacity of Electron for ~2x the price. In short, larger constellations benefit Firefly (until they don’t) and more orbital planes benefit Rocket Lab.