What's An Optimal Lunar Atmospheric Pressure For Reentry Vehicles?

“It’s a very very straight forward calculation any well motivated middle schooler could do.”

- Casey Handmer, unrelated

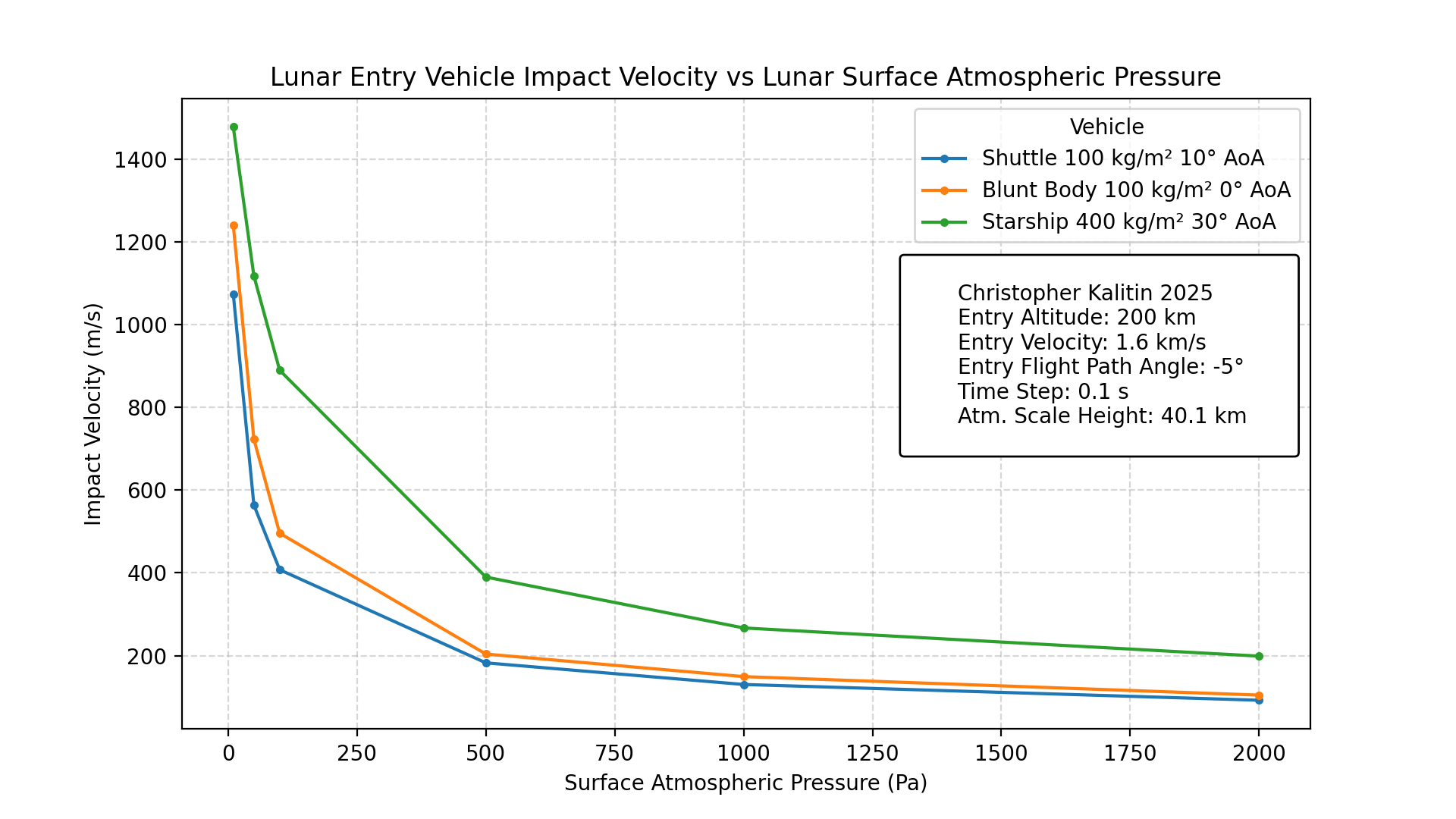

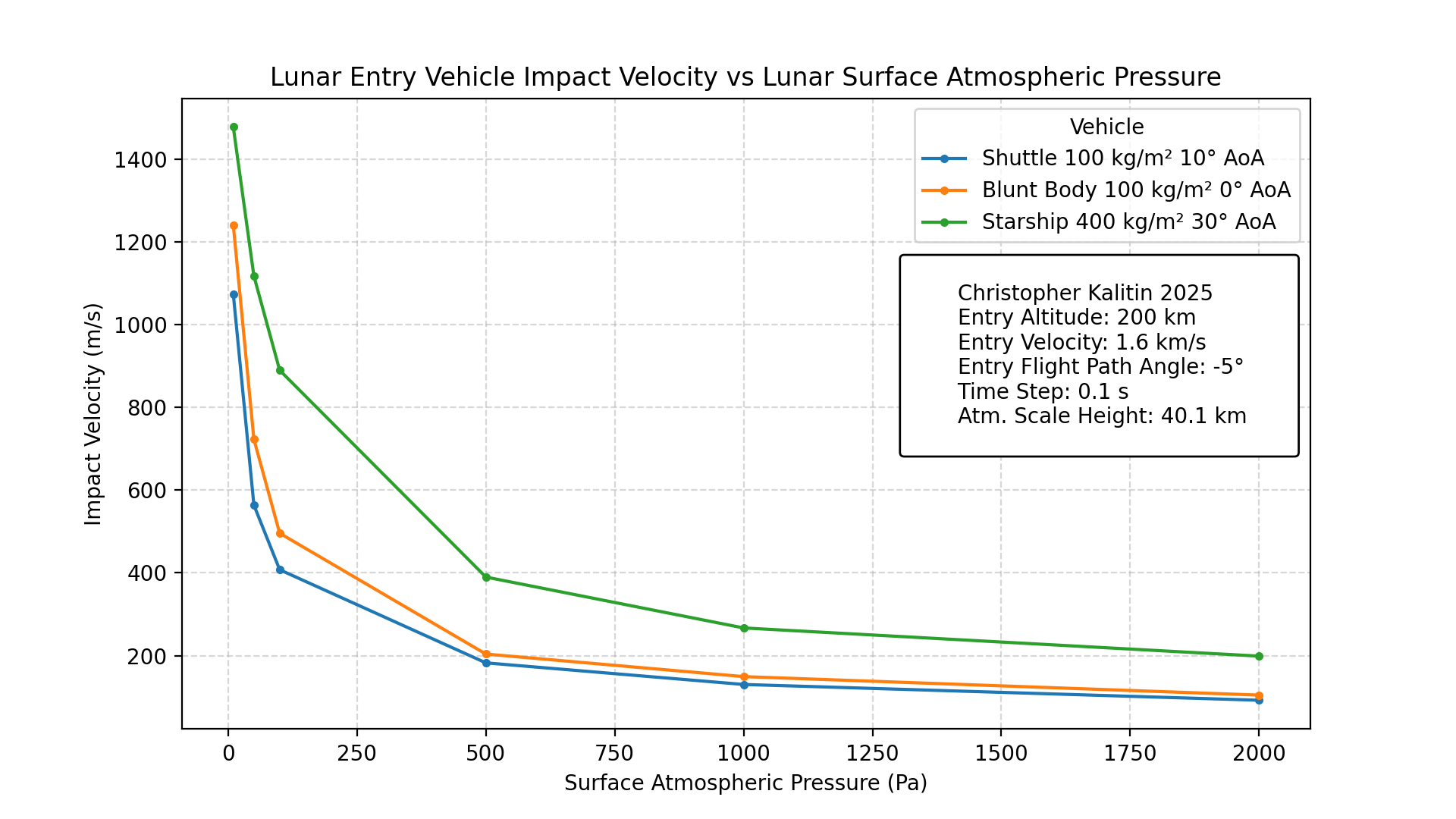

The final result: impact velocity vs. lunar surface atmospheric pressure for a few reentry vehicles.

The final result: impact velocity vs. lunar surface atmospheric pressure for a few reentry vehicles.

Three hours ago, I was nerd-sniped by this podcast with Casey Handmer, in which he starts gushing about how beautiful a lunar atmosphere would be. The effect this lunar atmosphere would have on spacecraft landing on the Moon was brought up, and I decided to adapt my Martian entry vehicle model to see how small you could make a lunar atmosphere while getting most of the benefits of atmospheric deceleration on landing.

All code is available here.

Atmospheric Parameters

The Moon’s atmosphere currently weighs about 25 tonnes in total, for a surface atmospheric pressure of 0.3 nanopascals. This is a small enough atmosphere that when the Apollo spacecraft fired their engines around the Moon, they increased the mass of the Moon’s atmosphere by double-digit percentages.

Molar Mass

Casey Handmer’s quick method for creating a lunar atmosphere involves melting the top 30 feet of the lunar regolith and letting the oxygen escape into the atmosphere. I’m not smart enough to conceive of a method for terraforming the Moon myself, so my assumption was a mostly diatomic oxygen atmosphere.

Depending on the region of the Moon you’re in, lunar regolith is composed of 42% oxygen, 21% silicon, 13% iron, 8% calcium, 7% aluminum, 6% magnesium, and 3% other trace elements. This mainly comes in the form of silicon dioxide, aluminum oxide, and iron oxide. So, it appears to be a safe assumption that the majority of the gas in a terraformed Moon’s atmosphere would be oxygen.

Hence, I assumed a lunar atmosphere mean molar mass of 32 g/mol, the same as diatomic oxygen. For reference, Earth is 29 g/mol (since N2 is 28 g/mol) and Mars is 43 g/mol (mostly CO2 at 44g/mol).

Temperature

Next, I assumed a uniform average temperature of 250 K. The mean surface temperature on Earth is 288 K, and on Mars, it’s 210 K. With the Moon closer to the Sun than Mars, I felt (Felt!) 250 K was a fair number. This is a one-night project; I’m fine with theoretical +/- 25% error bars.

Atmosphere Scale Height

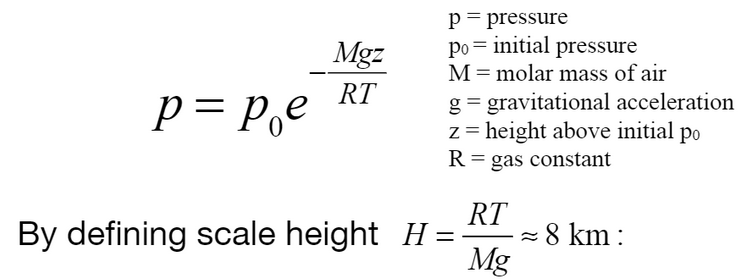

Scale height equation for an arbitrary body.

With temperature and molar mass, we can find the scale height of our lunar atmosphere. Scale height is the height at which the atmospheric pressure decreases by a factor of e (ie., ~37%).

Earth’s scale height is about 8.5 km, Mars’ is about 11 km, and Titan’s is ~15-50 km. We see above that scale height is a function of gravitational acceleration, so we expect a far lower value for the Moon.

Using the numbers above (250 K, 32 g/mol, 1.62 m/s^2), we find a lunar scale height of 40.1 km. This is significantly larger than Earth’s and Mars’, indicating a lunar atmosphere that falls off more slowly with altitude.

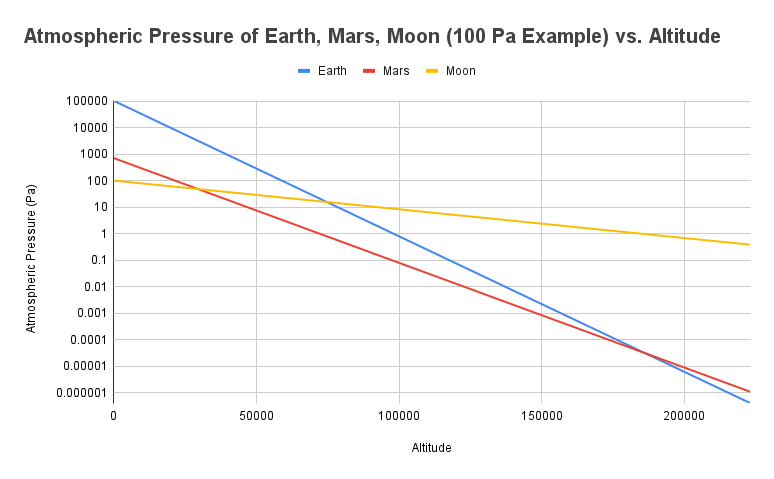

This illustrates how slowly our lunar atmosphere falls off.

To illustrate how extreme a scale height of 40.1 km is, above is a graph showing atmospheric pressure vs. altitude for the Earth, Mars, and an example 100 Pa lunar atmosphere. Notice how steep the lines are for the Earth and Mars, and how shallow the line is for the lunar atmosphere.

The Karman line defines the edge of space on Earth. This fairly arbitrary boundary is located at an altitude of 100 km. At this altitude, Earth’s atmospheric pressure is a little under a single pascal (0.79 Pa). Note that this value is not based on experimental data and instead uses this formula: p(h) = p0 * exp(-h/H), where p0 is the surface pressure and H is the scale height.

We can use the definition of space beginning at the altitude at which atmospheric pressure is 1 Pa. Using this definition, space begins 72 km above Mars’ surface. On our Moon, space would begin 185 km above the surface. That’s what extremely low gravity gets you! Especially for a body the size of the Moon!

To further illustrate just how far the Moon’s atmosphere would extend, we can consider the International Space Station. The ISS orbits the Earth at an altitude of about 400 km, and without boosts, it would reorbit due to drag in about one year. At this altitude, atmospheric pressure is 0.37 femtopascals (using the formula above, not experimental data). To reach the same pressure if the ISS was around our 100 Pa Moon, it would have to be 1,610 km from the surface.

Finally, note that, as Claude pointed out, there is extreme diurnal temperature variation on the Moon (120K to 390K). With a convective atmosphere this may be downplayed, but the atmosphere would still be 2x longer in some places than others (ie. in sunlight vs. in the shade of the Moon).

Simulating Reentry Through A Lunar Atmosphere

With some data on a theoretical lunar atmosphere with surface pressure as the input parameter (p0), I could adapt my Mars reentry model to simulate reentry of a blunt body vehicle through a lunar atmosphere.

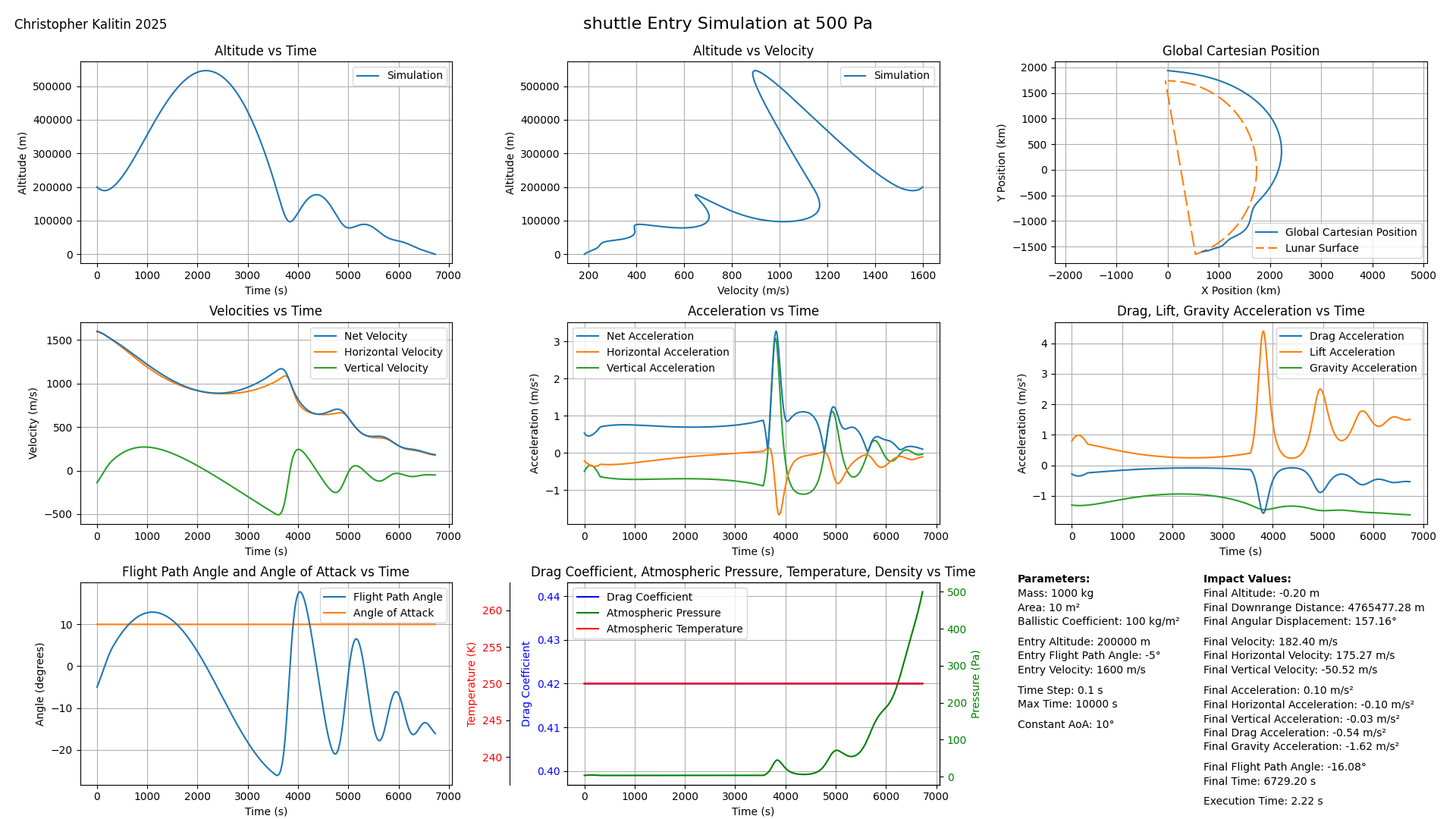

Space Shuttle Simulation

I’m getting tired and watching the Moon rise over the horizon and listening to white girl music (STARSHIPS WERE MEANT TO FLY!) as I write this, so I’m going to keep this brief.

My simulation uses interpolated lists of Cd vs. vel, LD vs. AoA, taken from various papers on Mars landers (mostly Phoenix) to simulate the entry of a blunt body vehicle through Mars’ atmosphere.

I was already stretching this when I put Starship into the simulation, so now I’m going to go even further and try to simulate a generic space shuttle reentry.

I found some papers and people on the internet with data on Cd, CL vs. AoA and vel for the Space Shuttle and blindly substituted these values into my simulation.

Expanded Image. Notice this multiple skip reentry with this space shuttle simulation at a constant 10 AoA.

If this graph makes no sense to you, I made some effort to describe it in the Initial Simulations and Convergence as a Function of Time Step section of this blog post.

Impact Velocity vs. Lunar Surface Atmospheric Pressure

Expanded Image. Notice the exponentially decreasing gains of a thicker lunar atmosphere.

With all of that intro out of the way, we can finally get to the result of this project (it’s all about the journey!). Using the initial state of a 1600 m/s 200 km orbit around the Moon (this would be 200x243 km), we set a flight path angle of -5 degrees to simulate entering the atmosphere.

We see that with a 10 Pa atmosphere, the vehicles barely slow down before impacting the surface. However, as we increase the atmospheric pressure, we see a lower impact velocity.

As expected, a higher ballistic coefficient (lower drag acceleration) and a lower angle of attack (less lift) result in a higher impact velocity.

At around 500 Pa, we get somewhat of a knee in the graph where we start to get diminishing returns on impact velocity. Hence, this may be an optimal surface atmospheric pressure for a terraformed Moon.

500 Pa is low enough that you won’t be able to go outside, but you could land a Starship while using ~400 m/s of dV, which is about the same as it takes to land a Starship on Mars.

Note that ~700 Pa is the surface atmospheric pressure of Mars. From a Mars lander and return vehicle perspective, this is a perfect atmospheric pressure. It’s high enough that you can use the atmosphere to decelerate and save fuel, while being low enough that you don’t face significant drag on ascent.