First Principles Thinking Expressed As Distillation Into a Latent Space

First principles thinking is the process of distilling complex ideas and source data into their most basic components, allowing for clearer reasoning, fundamental understanding, and a more efficient process of relating new insights to existing knowledge. Through this process, you collect source data, distill it into a latent space, operate in the latent space to derive insights, and then expand those insights back out into the world. This process has many parallels to machine learning.

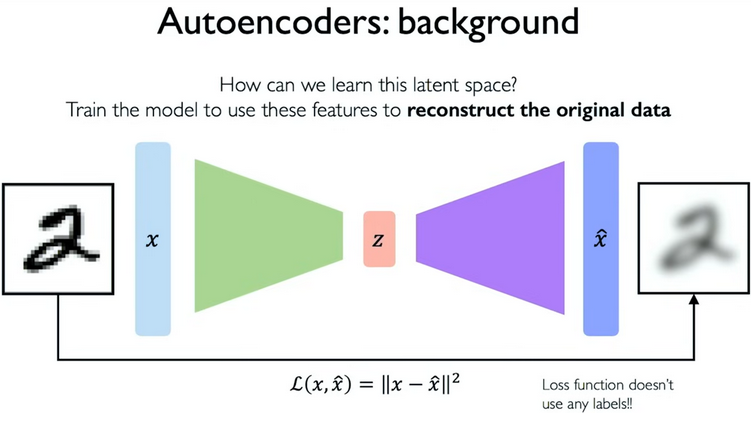

Autoencoders

This process can be described in relation to a variational autoencoder, a type of neural network. Autoencoders are a type of latent variable model that take an input space, encode it into a lower-dimensional latent space, and then decode it back into the original higher-dimensional space. The latent space - also known as an embedding space or feature space - is a compressed representation of the input data, capturing its essential features while discarding noise and irrelevant information.

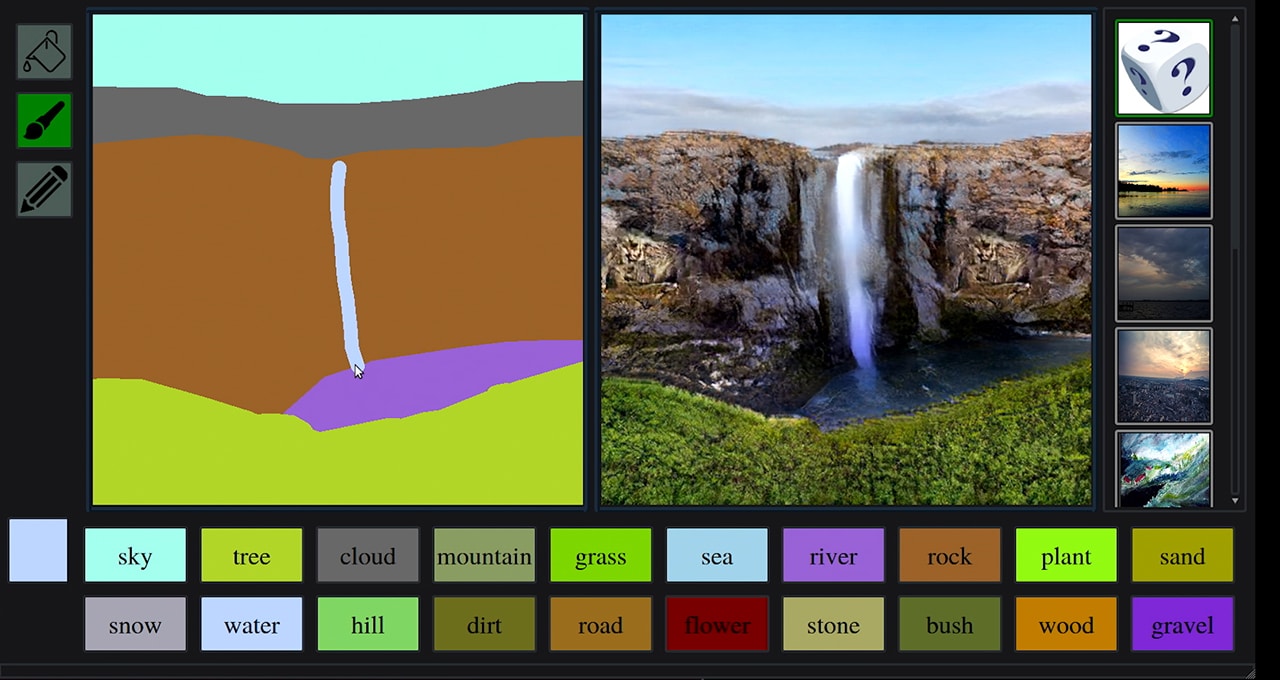

By adding noise or activating a particular feature in the latent space, you can generate new data. NVIDIA’s GauGAN model from several years ago is a good example of this, where you can draw a simple sketch with labelled features (“water”, “mountain”, “sky”, etc.) and from this compressed representation, the model generates a realistic image. Recently, Anthropic released Golden Gate Claude, a model in which they were able to map its inner workings and could activate the feature that was correlated with the golden gate bridge. This means the model was constantly thinking of the Golden Gate Bridge, leading to humorous results.

These examples from the AI world illustrate how extremely complex or large data can be distilled into a far simpler space, and in this space we can perform operations that would be impossible in the original space (eg. generating a realistic image from a simple sketch).

Lossless Compression, Then Performing Operations, Is Intelligence

First principles thinking is similar to autoencoders in that you, a human, can take a complex space of ideas and data and distill it into a latent space. This distillation process is the key to first principles thinking. Through asking the right questions and breaking down complex ideas into their fundamental components, you are losslessly compressing information into a smaller, more manageable form.

Once information is distilled into a latent space, it becomes considerably easier to perform operations and reason about it. You can compare this compressed idea to other compressed ideas, consider how your lower-dimensional representation relates to the original complex form, or expand your latent space back into the higher-dimensional space to see how a resultant idea derived from the essence of the original idea compares to the original itself.

Examples

To this point, my description has been necessarily abstract because of all the different ways first principles thinking can be applied. I’ll provide a few examples to illustrate this process in action.

1 - Jevons Paradox

A few months ago, I wrote about Jevons Paradox and Learning Rate. These are two disparate ideas that I have never seen related to each other. After a significant amount of thought and effort put into distilling both ideas, I came to the conclusion that Jevons Paradox is a special case of the principle behind learning rate.

Learning rate describes how given products get cheaper with greater scale, and Jevons Paradox describes how as the use of a resource becomes more efficient, the total consumption of that resource increases. These occur for the same fundamental reason: greater production leads to greater efficiency, which leads to lower costs, which leads to greater consumption.

As is common in the results of first principles thinking, the result of your thought appears entirely obvious in hindsight. However, if given just the input space and not the result, it is difficult to reach the same conclusion because the distillation step is on the critical path to understanding the relationship between the two ideas.

2 - Casey Handmer

“And over a long enough time scale, we can generate blog posts and books, both of which can embody compressed intelligence and a much higher signal to noise ratio than an average conversation.”

- Casey Handmer

Casey Handmer wrote a book titled How to get to Earth from Mars (available on Google Docs!) and realized that solar powered Sabatier reactors generating methane are on the critical path to getting to Earth from Mars. After expanding his input space to include solar cost curves on Earth and data about the hydrocarbon industry, he was able to come to the conclusion that solar powered methane production will also become the cheapest way to produce hydrocarbons on Earth, and that this will lead to a new era of energy abundance.

Casey Handmer wrote about this on his blog in various posts, such as How Terraform Navigated The Idea Maze, To Conquer the Primary Energy Consumption Layer of Our Entire Civilization, and Terraform Industries Whitepaper 2.0.

3 - Elon Musk

Elon reasoned from first principles about the purpose of government and capital allocation and came to the conclusion that “the government is essentially a corporation in the limit with a monopoly on violence” and that capital allocation should be done through the means in which has greatest efficiency, private corporations. This is again an obvious result in hindsight, but a tremendous amount of thought and distillation of complex ideas was required to reach this conclusion.

This thought process is essentially gathering a critical mass of source data about government, corporations, and capital allocation, distilling all of this into a latent space, then expanding out the compressed representation to see how these entities should be organized and coming to an actionable conclusion.

Source Data And Inference Bear Equal Importance

As alluded to in the Casey Handmer example above, collecting relevant source data is critical to the first principles thinking process. If you have too little source data, your inference step (thinking) will not be utilized to maximum ability, and if you have too much source data, you can lose signal in the noise and commit the sin of wasting computation.

This, by extension, is why you should learn everything. All source data can end up becoming relevant in computations you cannot anticipate yourself performing. Elon Musk or Casey Handmer did not know that when they were aspiring PhDs learning the fundamentals of physics, that they would one day be applying this knowledge to shape the future of civilization through industry.

“Contradictions do not exist. Whenever you think that you are facing a contradiction, check your premises, you will find that one of them is wrong.”

Atlas Shrugged. Source data and inference both serve as paths to resolving apparent contradictions.

Acquiring accurate source data and performing sufficient computation is also what Mentats and AIs do. Frank Herbert understood first principles thinking required both accurate source data and computation time when he wrote Dune, and this is why much of the role of the Mentats revolves around gathering and processing information. Furthermore, this is why LLM companies are so focused on acquiring high-quality training data and compute.

The Feynman Algorithm

- Write down the problem.

- Think very, very hard.

- Write down the solution.

I recently read Casey Handmer’s How to reason from first principles, and earlier found the original iteration of this blog post from 2019. In these blog posts and this interview with Jason Carman, Handmer describes the “seven Ds and little s” method of solving physics problems.

This method consists of:

- Diagram

- Directions

- Definitions

- Diagnosis

- Derivation

- Determination

- Dimension Check

- Substitution.

Both this method and my explanation of first principles thinking can be thought of as derivations of the Feynman algorithm.

My explanation involves distillation of relevant source data into a latent space (writing down the problem), thinking very, very hard, and then expanding your insights back out into the world (writing down the solution). The 7 Ds and little s method involves creating a labelled diagram of the problem, thinking very, very hard about what method to use to solve the problem and how to apply it, then substituting values into your derived equations to arrive at a solution.

If you load my explanation of first principles thinking, the 7 Ds and little s method, and the Feynman algorithm into your input data space, losslessly compress them into their fundamental elements, then compare them, you will likely find that they are all instantiations of the same underlying process. This is the power of first principles thinking: it allows you to see the commonalities between seemingly disparate ideas and methods, and derive new insights from them.

“To think from first principles

you must first

return to retard.”

- Yacine

[Update Aug 19 2025]

Here’s a video about The College Dropout where this guy explains the exact process I described but in the context of music:

- Artist begins with an abtract idea

- The artist distills this into a piece of art (Compressing the big idea into quippy Kanye lyrics)

- The listener expands the distilled representation back out into the original idea

This is also why the experience of listening to Kanye songs is exceptionally wonderful.