Extrapolating Demand and Competition for the 1-ton Rocket Class

Peter Beck responded to this blog post here.

Tell me where I’m wrong or just give compliments here.

Today four of the best space investing Youtubers posted their interview with Peter Beck and Adam Spice of Rocket Lab. Responding to one of Dave G’s questions, Peter Beck said this about the 1-ton rocket class: “Our view of 1-ton is it’s kind of a no man’s land.”

During this year I’ve written a few blog posts on the topic of 1-ton class rockets: Comparing Demand for Firefly’s Alpha vs. Electron, Small Sat Constellations: The line between Electron and Rideshare, and Visualizing Small Sat Constellation Tradeoffs with Charts. The primary insights from this research have been that there is little competition between the 1-ton rockets and Electron and that currently there is only a small niche of the constellation market that is optimal for the 1-ton class. Peter Beck’s comments help to confirm some of my conclusions and prompts more research into the small sat constellation market.

In this blog post, I’ll use my dataset (Based on Jonathan Mcdowell’s public data, Gunter’s Space Page, and others) to quantify how big the market for the 1-ton class rockets is.

Don’t Extrapolate the Early Launches

Despite the difference in size, Alpha’s and Electron’s first few flights resembled each other closely. Firefly’s Alpha has flown 5 times to date and 3 of these missions were rideshare as part of their DREAM program or for NASA. This is the same as the first five Electron launches, 3 of them were rideshare carrying assorted satellites for Planet Labs, Spire Global, or NASA’s ELaNa program.

As Alpha’s and Electron’s early launches proved, the first few launches of any vehicle are risky. This means that the first few launches of a new rocket are underpriced to account for the risk. The effect of this is the first few launches are not indicative of the future market due to the cheaper pricing. For example, in the last 3 years, Electron has launched 3 rideshare missions out of 28 total launches. “Beginning Of The Swarm”, “Baby Come Back”, and “There And Back Again”. This amounts to ~10% of their launches vs. 60% during the first 5 launches. This is why we cannot directly extrapolate the first 5 Firefly launches and expect an accurate result.

“It’s too small to be a useful rideshare vehicle and it’s too big to be a dedicated vehicle.” - Peter Beck. In this quote - again from the Dave G interview - Beck is referring to competing with Falcon 9 rideshare missions where specific orbit parameters and timing are worth sacrificing for a significantly lower cost. This reflects the early Alpha and Electron flights which were underpriced to account for the risk. However, Rideshare missions are not sustainable long-term on small launch vehicles because SpaceX has far better pricing power. In the second half of the quote, he says a 1-ton class rocket is too big to be a dedicated vehicle. This is because the vast majority of payloads that need the specific orbits and launch dates only available on dedicated launches are light enough to be launched on Electron, which is ~2x cheaper than Firefly’s Alpha.

Most Constellations Are Optimized for Electron

The over-representation of rideshare missions is not the only source of uncertainty. The biggest upcoming market for rockets of all classes is constellations (70% of Rocket Labs 2024 launches so far). Small sat constellations are an even younger market than small sats themselves, so assumptions will have to be made in extrapolating the size of the market. The biggest assumption is what the distribution of satellite mass and total satellite count will be in upcoming constellations.

The competition between Alpha and Electron to launch constellations has parallels to the competition between Electron and Falcon 9 to launch small satellites. Electron fills the niche of payloads that either need unique orbits or an accelerated launch date. Because Falcon 9 is unable to properly serve these satellites, Electron can charge a higher price for a dedicated launch. Electron can’t compete for the vast majority of small satellites launched by SpaceX on price, but they have a strong niche in the satellites that require their services. Alpha won’t be able to compete for most Electron payloads because of cost, but they can create their own niche in the 1-ton class. The largest component of this niche is constellations that are optimized for 1-ton class launch vehicles.

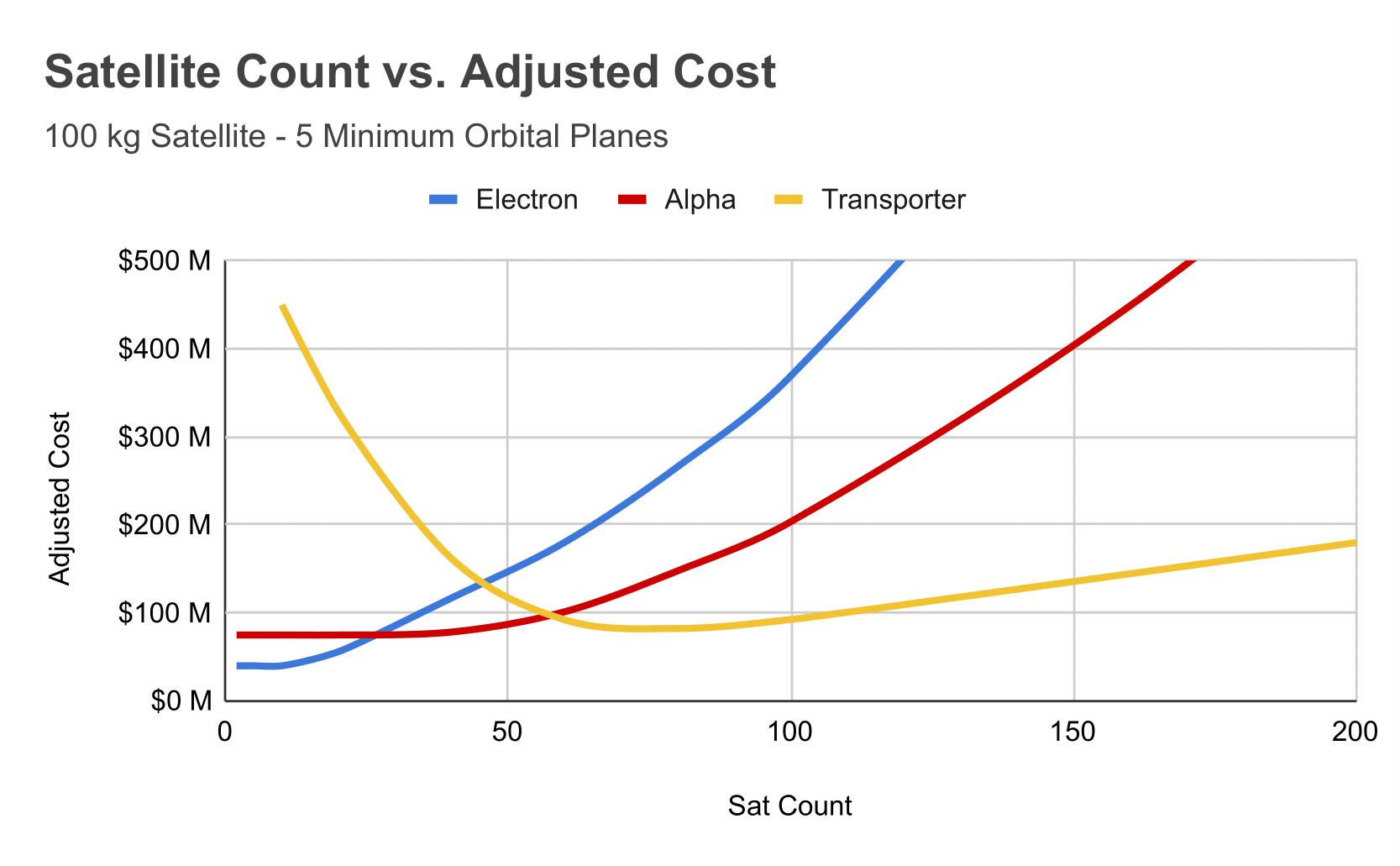

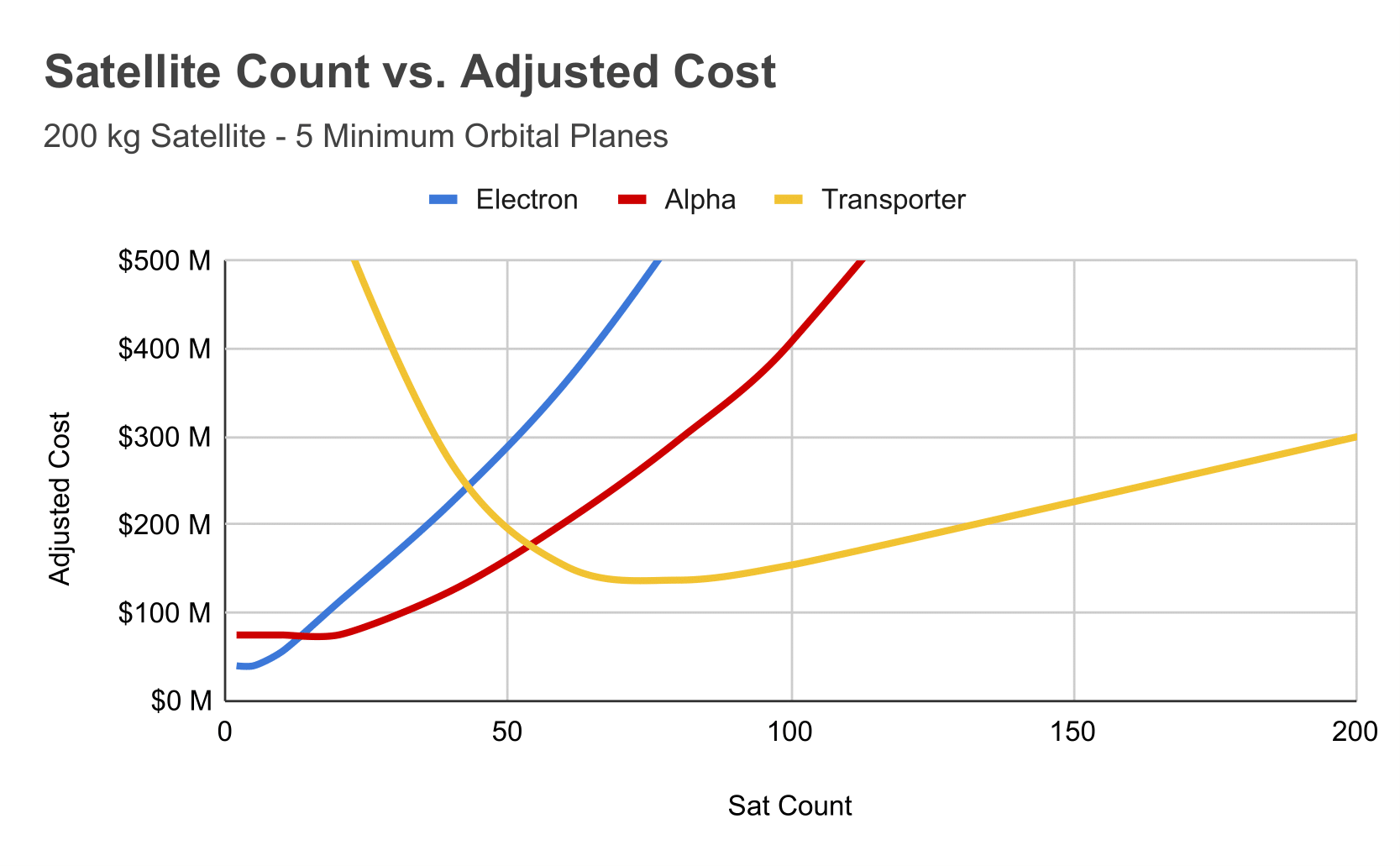

In my previous blog post I created the beautiful charts you can see above that visualise the trade-offs between Electron, Alpha, and Rideshare in launching small sat constellations. Assuming you are using 100kg satellites, only when you exceed 25 satellites in your constellation does a rocket on the scale of Alpha become economical. Furthermore, the lower cadence of Alpha means Electron sees a further cost advantage.

The cost advantage of Electron starts to diminish when you increase the mass of the satellites. This is the strength of the 1-ton class rockets, they are the most efficient way to launch heavy and relatively small constellations. Satellites between 150-500kg in constellations of between ~25-100 total satellites are the optimal market for the 1-ton class rockets. The issue is none of these constellations currently exist, hence Peter Beck saying: “Our view of 1-ton is it’s kind of a no man’s land.”

The heaviest commercial Earth Observation satellites are operated by Capella. Six of these 112kg satellites are currently in orbit and were launched on either Electron or Falcon 9 rideshare missions. These satellites are not heavy enough and not launched at a high enough scale to take advantage of Alpha’s 1-ton payload capacity.

Are We Seeing a Military Constellation?

Lockheed Martin and L3 Harris have purchased up to 20 and 25 launches from Firefly respectively. It is not clear what payloads will fly on these missions and even if Lockheed Martin purchased flights on Alpha or MLV.

However, if launches are being purchased this far ahead in bulk it may be likely that these are for a potential constellation. The national security nature of these companies may also mean there is a responsive space aspect to these contracts that takes advantage of the capability Firefly developed for their Victus Nox mission.

Assuming these satellites are for a constellation, the choice of Firefly to launch them may be due to the fact that the satellites are heavy enough to take advantage of Alpha’s payload capacity. Earth Observation satellites seem to level out at the ~100kg mark, but other applications may require heavier satellites. For example, various Starlink satellite iterations have been between ~250kg and ~800kg. If we are seeing the early stages of a military constellation, it may be that the hardware required for these satellites makes them fit into the class that can leverage the Alpha’s 1-ton payload capacity.

The very forward-looking nature of these contracts may mean they don’t materialize as This Guy (hilarious name) has theorised. Furthermore, my analysis is based on the data shown in the charts above. This doesn’t take into account industry partnerships and other business factors.

The Two Categories of Satellites That Will Use Dedicated Small Launches

The first category of satellites that get their own dedicated small sat launch we’ve seen are those that use Electron for one of its unique capabilites. Compared to rideshare, Electron can launch to a specific orbit on a specific date. For commercial customers, this has meant a quicker time to revenue which should not be underestimated. Government customers have also taken advantage of the ability to launch to a specific orbit. For example in April they won a contract to launch a set of satellites for the US Space Force to a Very Low Earth Orbit (VLEO).

This category of payloads isn’t very well addressed by Alpha because of the low mass of the payloads. For example, the USSF VLEO satellites weigh 200 kg in total. When payload capacity is not a concern, the cost advantage of Electron is a very large factor.

Peter Beck addressed this in his interview with Dave G: “If you look at the payloads that we’re lifting they’re all sort of in that 200kg class, so the whole reason someone comes to a dedicated rocket is because they want a dedicated rocket. So putting a 200 kg payload in a one-ton lift class, I just don’t see how you can be economic to be able to compete with a smaller 300 kg lift class.”

The second category of payloads we will see launch in the next few years are those that are too heavy for Electron and too light for Falcon 9. Just as Electron launches all satellites too light for Alpha, Alpha will be able to launch all satellites for light for Falcon 9. Because of the lack of competition and Falcon 9’s utter dominance of the launch market during the last few years, it has launched several satellites to LEO that are far below its 18-ton payload capacity.

In order of most recent to least recent:

- Korea Project 425 (800kg) (Anchor customer on Bandwagon-1)

- iMECE (800kg)

- EROS C3 (400kg)

- Globalstar-2 FM15 (715 kg) (Rideshare with Starshield)

- IXPE (330kg)

- Paz (1,400kg)

- Formosat 5 (525kg)

- Jason-3 (553kg)

- CASSIOPE (481kg) (First commercial Falcon 9 launch)

Given the 4x lower cost of an Alpha launch compared to a Falcon 9 launch, it is likely that Alpha will be able to compete for these payloads. Falcon 9 has launched less than one of these satellites per year over its lifetime, so the market is not large on SpaceX’s scale. However, on the scale of Alpha, one launch per year is significant enough to mention.

Responsive Space

Sticking with the common theme of the 1-ton class filling niches, Responsive Space is a potential market for Firefly. Alpha’s third launch was Victus Nox, a launch for the USSF that demonstrated its ability to launch a satellite within 24 hours of receiving the payload. To be able to launch a satellite so quickly, Firefly already had a vehicle at the launch site ready to receive the satellite and launch.

Rocket Lab was recently awarded a contract for the Victus Haze Tractically Responsive Space (TacRS) mission. This entails two launches, first True Anomaly’s Jackal autonomous orbital vehicle, then a modified Photon spacecraft. The launch of the modified Photon will prove Rocket Lab’s ability to launch in under 24 hours from receiving an order to and then maneuvering in orbit and performing rendezvous and proximity operations (RPO). Just like Firefly’s Victus Nox mission, Rocket Lab will keep a vehicle in a “Hot Standby Phase” before the launch is ordered.

Awarding Rocket Lab this contract shows that the US Military is interested in multiple providers for responsive launches. Furthermore, tasking Rocket Lab with modifying a Photon spacecraft to perform RPO operations hints at the goals of creating responsive space assets. RPO allows you to shoot down enemy satellites. Firefly also builds Elytra, their orbital kick stage. We could see competition between the two companies for responsive space launches in the future.

Quantifying the Size of the Market

In the future, there will be four primary categories of launches for Firefly’s Alpha, the most prolific 1-ton class rocket. These are constellations, dedicated large satellites, responsive space launches, and rideshare missions. The primary source of uncertainty in predicting the future of this market is the unknown requirements and goals of military customers. The military is understandably secretive about their plans and this makes it difficult to predict how many responsive space or constellation launches they will purchase in the future.

The current market Alpha enjoys with rideshare missions will not continue into the future because they are underpriced to account for the risk of early launches. These previous launches are underpriced in order to find customers for initial launches. With increased prices in the future, the primary reason to conduct this type of rideshare mission is an accelerated launch date compared to Falcon 9 rideshare missions. Since 2022, Electron has launched a single rideshare mission of this type.

Electron’s other rideshare missions have either had unique requirements or were payloads tagging along with a larger primary payload. The recent “Beginning Of The Swarm” mission launched the NeonSAT-1 and ACS3 satellites to different orbits on a single mission by utilizing the Photon kick stage. About a year before this, Rocket Lab launched the “Baby Come Back” mission with the 30kg Teleset LEO 3 satellite and various smaller payloads for Spire Global and NASA. Firefly will be able to launch these types of missions with their Elytra kick stage and by ridesharing small satellites with larger primary payloads.

The market most well suited to Alpha is ~1-ton satellites. Judging from the earlier Falcon 9 missions, there may be one satellite per year that Alpha will be able to launch in this market segment.

The US Military has not made public how many responsive launches they will conduct in the future. This makes it difficult to predict the size of this market in the future. Given the competition betwene Firefly and Rocket Lab for these launches along with the developmental nature of these contracts, Firefly could see a responsive space mission every 1-2 years. Please argue with me if you have a differing view.

By far the market with the largest potential for Alpha is constellations. Currently, there are no constellations that have satellites massive enough and launched in enough numbers to take advantage of the payload advantage of Alpha, so we can only speculate on Lockheed Martin and L3 Harris’ contracts and extrapolate from Electron. During the first 7 months of 2024, Rocket Lab conducted 7 constellation launches. According to Wikipedia, they have 23 planned constellation launches between 2024-2027. Given the fact that Electron will likely sign more contracts before 2027, the number of constellation launches over this timeframe should be 10-15 per year.

Earth Observation constellations don’t appear to require Alpha’s 1-ton payload capacity, but military constellations may be well suited for it. Lockheed Martin and L3 Harris both contracted Alpha for about 5 launches per year during a 4 year period. These periods have slight overlap, 2025-2029 and 2027-2031 respectively. We don’t know what payloads are planned for these launches and during such a preliminary stage it is unlikely large sums of money have changed hands. For these reasons, the launch contracts should be discounted for the fact that they may not materialize. Around 3 constellation launches per year (Either military, large earth observation satellites, or other) is a reasonable estimate.

Conclusion

Summing the potential launches listed above, we get demand for about 6 launches per year. The breakdown is 3 Constellation, 1 Dedicated Satellite, 1 Responsive Space, and 1 Rideshare. Assuming an average price of $15M, this is a $90M market. Comparing this to ~20 $8M Electron launches per year, Firefly’s TAM is about 50% of Electron’s upcoming launch rate. This assumes that Firefly realizes the constellation market and that Electron launches don’t substantially increase. Specifically looking at constellations - as they are the largest and fastest growing market - Firefly could launch 3 missions per year versus Electron’s ~10-15. The higher price of an Alpha flight makes the gap smaller than the launch counts imply, 60% vs. 80%.

All the payload categories I’ve delved into above should make it clear that there is little overlap for competition between Electron and Alpha. Similar to Electron vs. Rideshare, Alpha is not cheap enough to take Electron’s core market. Rather, it will create its own niche just as Electron has against Falcon 9 Rideshare.