Can Canada Support a Sovereign Space Industry?

For feedback / criticism (which is well appreciated!) respond here or email me (christopher.kalitin@gmail.com).

The CEO and Founder of NordSpace responded to this blog post here.

Introduction

Today I read this Space News article about Nord Space, Canada’s first launch vehicle startup ever.

While I’m generally sceptical of all space startups - hardware is already extremely difficult and this is one of the most unforgiving domains ever - some of the points made in that article prompted me to consider the market for a domestic launch provider in Canada more seriously.

Particularly, the founder was optimistic about sovereign launch demand in Canada, creating a regulatory framework for launches here, and the aerospace supply chain around their HQ in Ontario.

Domestic Canadian Launch Market

Historic Data

Enlarged Image

Enlarged Image

Note these are Canadian payloads (As categorised by Jonathan McDowell in his dataset psatcat) launched on any nation’s launch vehicle. Ignore the lower counts of the simple payload category chart (eg. 15 vs 18 in 2023), those are wrong, Python is being goofy.

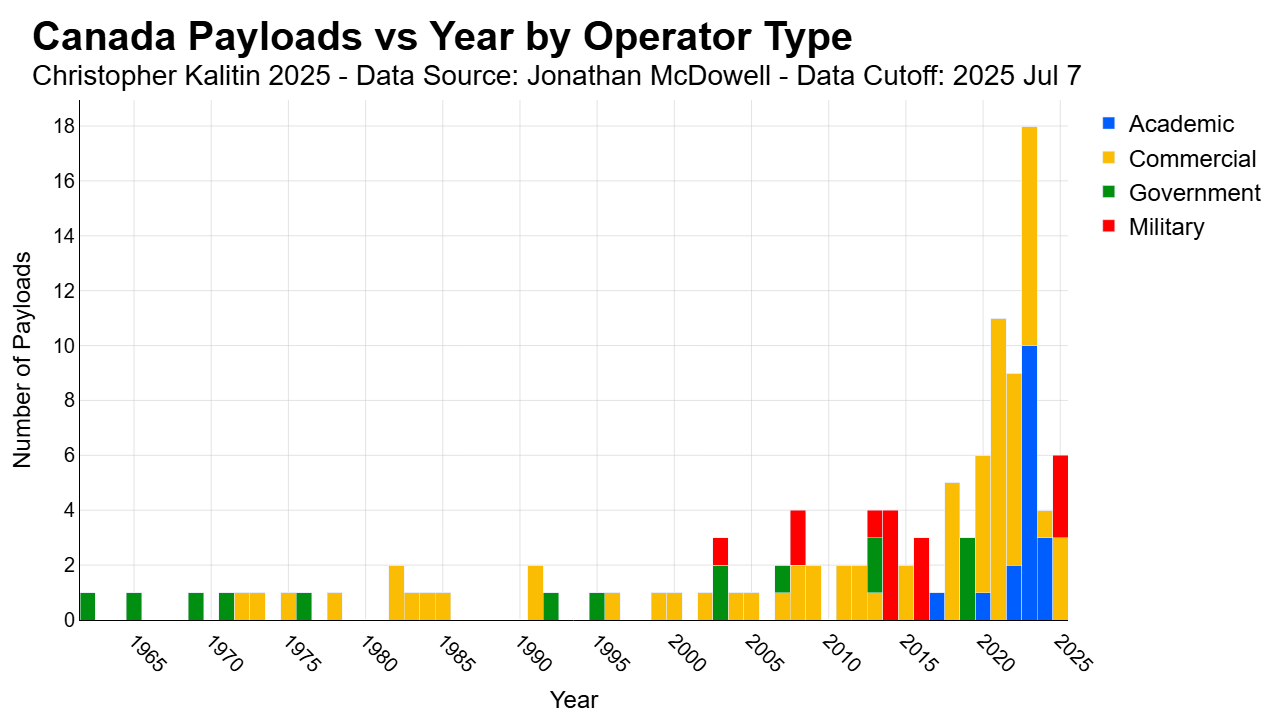

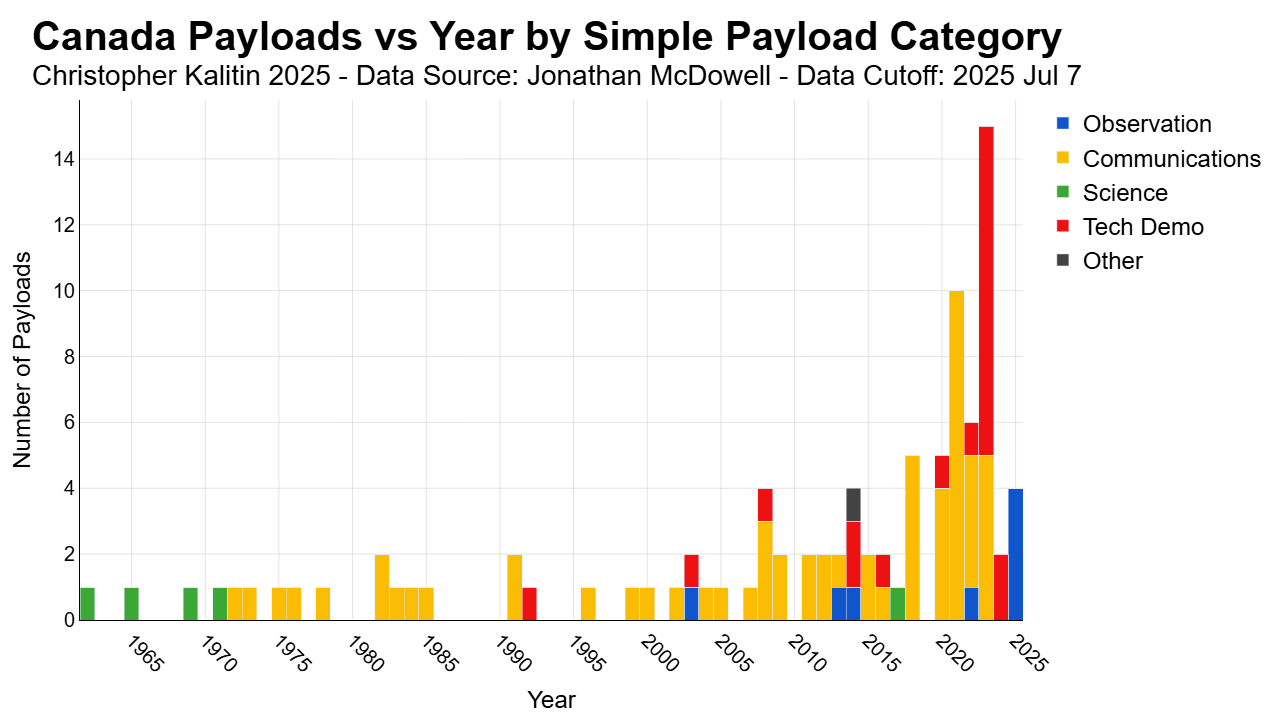

To begin my analysis of the Canadian Space Industry, I used my McDowell Dataset Analysis repo to generate a few charts about the history of Canadian Payloads that have successfully made it into orbit.

On net, only about 100 Canadian satellites have ever been launched into space.

A positive sign is that the trend in Canadian payloads looks roughly exponential, and it feels like you could fit an exponential to them without much worry. However, seeing as there were only 10 payloads launched in 2024 and 2025 so far, we need to carefully check our assumptions before predicting extreme growth.

Upcoming Canadian Payloads

A SpaceQ article by Marc Boucher claims there could be 36 Canadian satellites launched in 2025. Some of these are unlikely, like 8 satellites that are built and operated by NorthStar under a “space-as-a-service” deal with Spire, which sued them after one of their previous satellites was lost and three had unusable data.

The majority of upcoming Canadian satellites are launching on SpaceX’s Transporter 15 mission in October. There are 9 of EDA’s Earth Observation satellites and the first 10 of Kepler’s Optical Data Relay Network communication satellites. An honourable mention is the University of Toronto’s Aerospace Team launching a 3U imaging satellite. Hopefully UBC can get on this list in the future!

Unlike the American space industry, dominated by thousands of Starlink satellites, the Canadian space industry is small enough that University design groups get a mention! The group of 10 academic satellites in 2023 were mostly launched on SpaceX’s CRS-27 mission to the ISS. These all come from Universities around the nation, from Manitoba to Yukon.

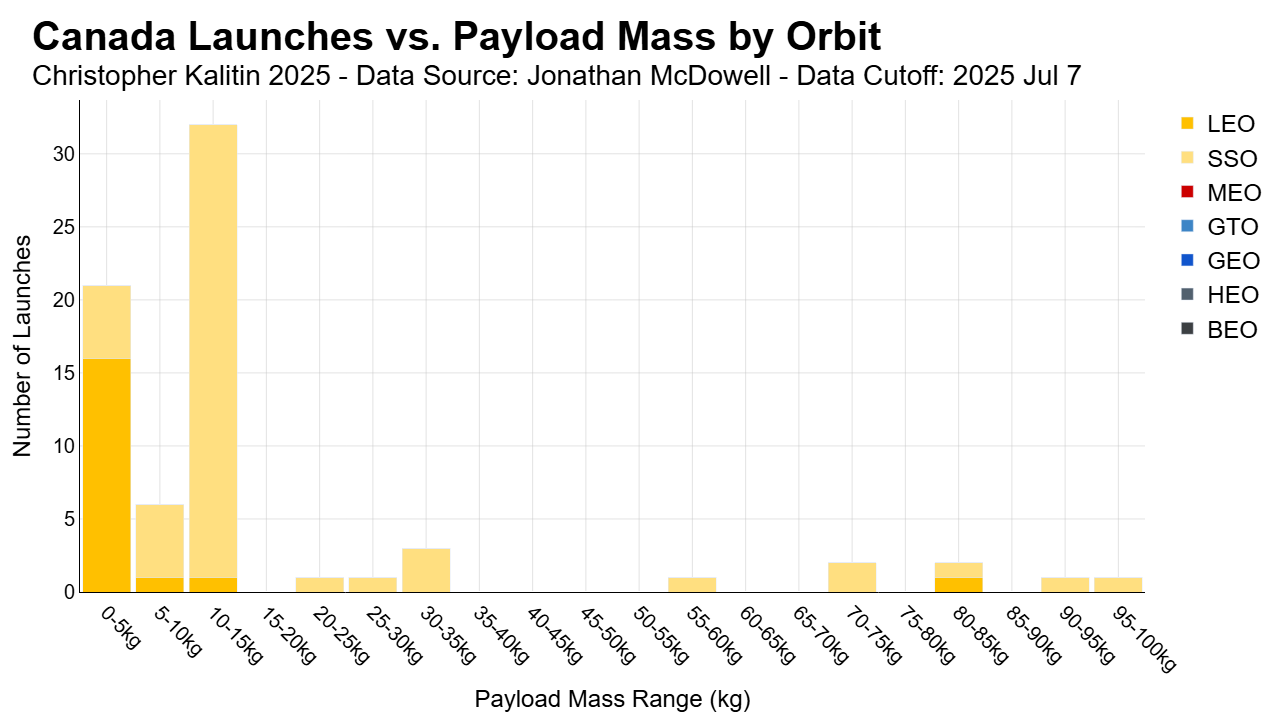

Mass Distribution of Canadian Satellites

Enlarged Image

Enlarged Image

Enlarged Image

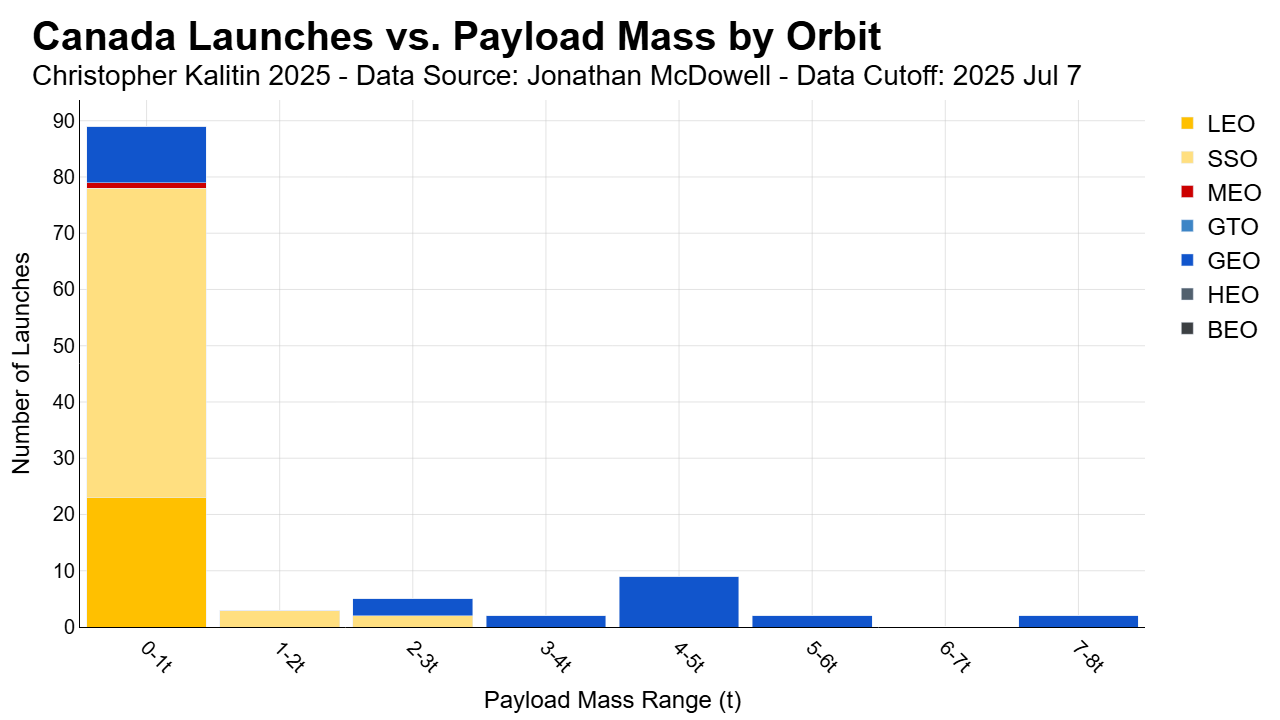

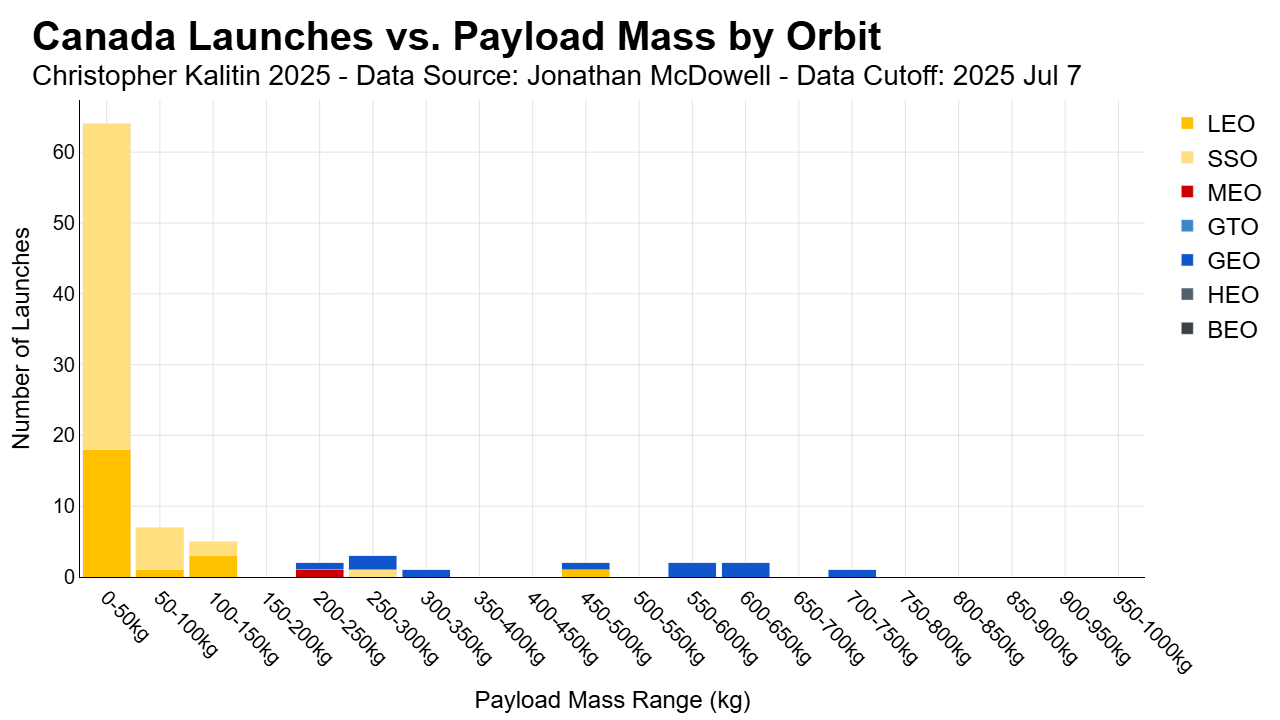

These charts show in progressively more detail the mass distribution of Canadian satellites. Satellite count vs. payload mass.

The vast majority of Canadian satellites weigh less than 15 kg. These consist of Kepler’s communication satellites, various University projects, and GHGSat’s Earth Observation satellites. Kepler is based in Toronto and is focused on high-bandwidth In-space data relay for LEO spacecraft, particularly remoate sensing missions. GHGSat is based in Montreal (Where I’m flying in a few weeks go please reach out if you’re around there!) and monitors primarily methane and carbon dioixde emissions.

The higher mass geostationary satellites are mainly communication satellites. Telstar 18V and 19V were launched on Falcon 9s in 2018 and provide communication services. Anik F3 was a 4.6 tonne satellite launched on the Proton-M rocket and is also a geostationary communications satellite. RCM-1, -2, -3 are C-band synthetic aperture radar satellites in Sun Synchronous Orbit that weigh ~1.5t. They were built by MDA and operated by the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).

Analysing NordSpace’s Founder’s Comments

“They’re [Canadian Department of National Defence] the ones who really are sending the strongest demand signals. We’re not excited about relying on foreign partners, no matter how close they may be, to get our assets to space. We have all these payloads that kind of just sit on shelves. Let’s just toss them on your rocket and get them up there.”

Rahul Goel, NordSpace Founder

The founder of NordSpace seems optimistic about the potential for the Canadian defence industry to be a big source of demand for NordSpace. We’ve seen in the past with programs like NASA’s Venture Class Launch Services (VCLS) or lane 2 of NSSL phase 3 that government programs have a great potential to kick-start launch companies. So, this is certainly a market that should always be considered for new space startups.

A few months ago at the SmallSat Europe event in Amsterdam (And elsewhere, but I can’t find a better source), Peter Beck said that European launch startups would have to rely on government payloads to get off the ground before they are commercially competitive. These are one of the primary markets for European launch startups, as in national defence sovereign launch capability is far more important than in commercial markets.

Firefly announced a launch site in Sweden to seemingly capitalise on the subset of the European launch demand that prefers launch on their own soil.

Looking at the chart at the top of this section, we see only 6 Canadian military payloads launched in history. Some of these may be mislabelled, and I only just noticed 3 were labelled incorrectly as commercial when they were part of a Defence Research and Development Canada program. However, there is clearly a scarcity of Canadian military payloads as far as I can tell.

Goel claims there are payloads sitting on shelves, and he certainly has greater insight into the Canadian defence market than I do, but there isn’t any evidence I can find of substantial Canadian military launch demand. Canada currently relies on US military space assets, maybe this will change in the future.

Challenges With Building Rockets In a Country Where It Hasn’t Ever Been Done

The most visible issue with building rockets in Canada is that there are no launch or test sites. NordSpace’s test site is an abandoned mine that they found after searching “every location you can imagine.”

“In Canada, [if] you mentioned to anybody that you’re building a rocket engine and you want to test it on their farm or on an industrial plot, they’re just going to have an allergic reaction to it right away. We got kicked out of every location you can imagine.” Rahul Goel, NordSpace Founder

The lack of any launch or test sites means you are required to build your own. As Rocket Lab at Mahia or SpaceX at McGregor can attest, having your own test/launch infrastructure can be a great advantage in launch vehicle programs. This is especially true in SpaceX’s case, where they bought McGregor from the bankrupt Beal Aerospace for a fairly low price (Eric Berger goes into this in Liftoff). However, for early-stage companies, you want to buy down technical risk and focus on reaching milestones early. So, vertical integration is not ideal for a startup if it isn’t required.

Peter Beck danced with the indigenous people of New Zealand to be allowed to build a launch site on land they had the rights to. Goel’s quote gets to a similar mentality in Canada, where it’s also particularly difficult to build risky test sites.

Their launch site is located at 46-degrees latitude on the coast of Newfoundland. This is less than the 49-degrees latitude of Baikonur Cosmodrome, so they could access the International Space Station. However, future US commercial space stations are under no obligation to launch to higher orbital inclinations. A higher inclination also requires more energy expenditure to reach a Geostationary Orbit, which lowers payload capacity. On the other hand, Sun Synchronous Orbit can be accessed from anywhere as it’s ~95 degrees inclined. Many Earth Observation satellites use this orbit.

Finally, there’s lower capital availability in Canada than in the US. To raise money for Electron, Peter Beck flew to Silicon Valley and got a cheque from Khosla Ventures. If NordSpace is trying to be explicitly Canadian, this is less of an option.

Positives Of Being A Non-US Non-Government Launch Program

Although there are many challenges, it’s not all negatives!

In the same Space News article I’ve been mentioning Goel, says that within 10 km of their headquarters, there are five critical suppliers to SpaceX’s Merlin and Raptor engine programs. Even though they’re in Canada, they aren’t too isolated from US Aerospace technology.

Because NordSpace is a private company, they aren’t subject to the same whims of government as programs like the Avro Arrow. They may rely on domestic payloads, but the vision and execution for how they launch these payloads is all up to them. This is the same reason why SpaceX will take us to Mars and why NASA has failed for decades.

My favourite advantage of a non-US launch company is that they are not subject to ITAR. This means you don’t need to be a US citizen to work there. For countries that don’t want to go through ITAR regulatory approval processes or individuals that can’t be bothered to become US citizens, NordSpace presents an easier path to space or working on space.

Proactive Launch Range / Regulatory Strategy

Canada has no regulatory launch approval process. NordSpace’s strategy for solving this problem is to be proactive about working with the government to build such a framework. They are aiming to get a full orbital launch approval for their upcoming 2025 suborbital launch of their Taiga rocket.

Rocket Lab had to go through a similar process to get approval to launch from New Zealand and to get ITAR approval to launch US military payloads from their Mahia launch site.

They plan on building out their launch site with two pads. One for themselves, the other for a theoretical customer in the future. They hope for another company to come around and use this pad, whether a local Canadian company or an international company. Like discussed in the previous two sections, I’m not sure of the benefits any company could get here aside from not having to go through ITAR approvals - assuming they don’t want to launch US military payloads from Canadian soil.

Examining NordSpace’s Launch Vehicle Strategy

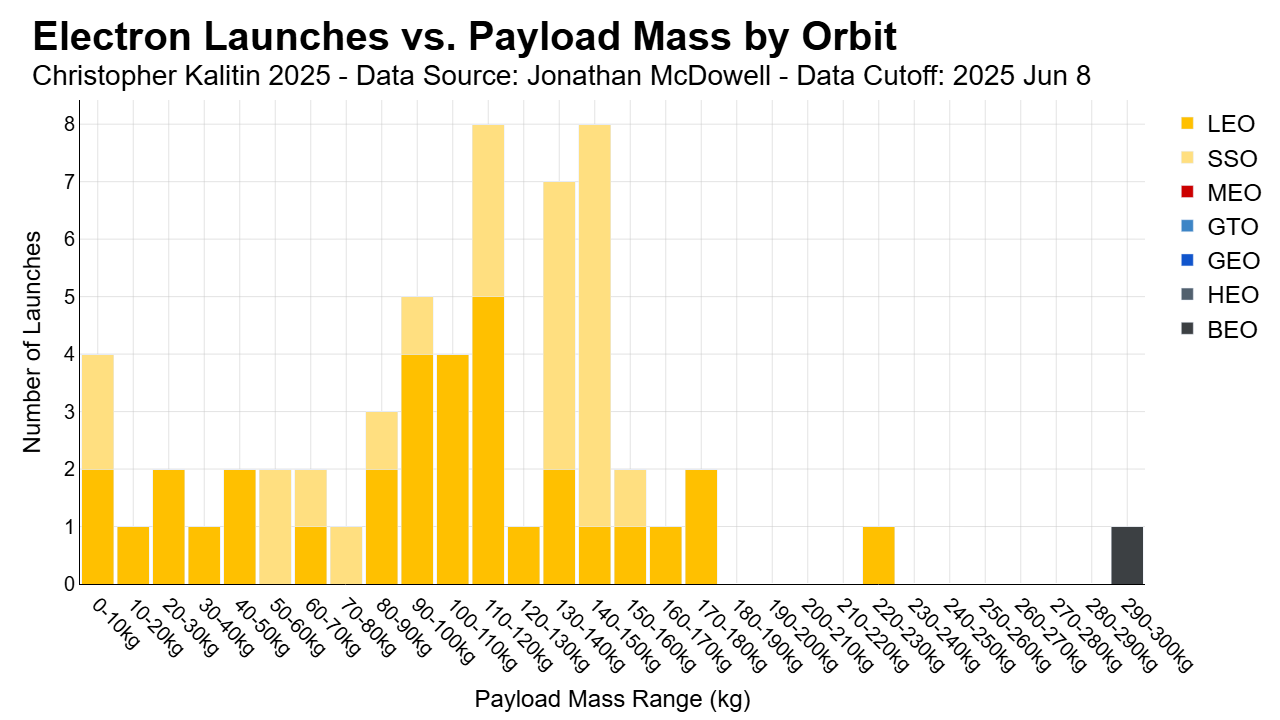

Enlarged Image

This is my chart of the payload mass distribution of Rocket Lab Electron launches.

NordSpace has plans for 3 launch vehicles:

- Taiga - Hypersonic Suborbital Space - 50 kg payload

- Tundra - LEO Small Sat Launcher - 500 kg payload

- Titan - LEO Medium Lift Launch Vehicle (MLV) - 5,000 kg payload

A hypersonic suborbital launch vehicle is an interesting first vehicle. As Rocket Lab’s HASTE program has demonstrated, there is a non-trivial amount of hypersonic testing demand from US military contractors. This may be true in Canada as well, so NordSpace may continue to have demand for Taiga after their larger launch vehicles come online. A small vehicle is obviously the right choice for their first rocket to demonstrate their ability to build rockets - Stoke Space seems to be the rare exception here.

I have written extensively about the 1-ton class launch vehicles like Firefly’s Alpha in the past, so a Neuron instantly activated in my mind when I saw they were aiming for 500 kg, instead of something lower like the ~100 kg capacity of Astra’s Rocket 3.3.

In short, most payloads will not use the full payload capacity of 500 kg. Looking at the payload mass distribution of Electron launches, we see that there isn’t much merit in going above a 200 kg payload capacity. The exception is for constellations that contain satellites with high individual masses or launching heavier individual satellites - not many of either of these exist. I go into far more detail in my blog post Extrapolating Demand and Competition for the 1-ton Rocket Class, which Peter Beck responded to!

In my blog post Stoke’s Nova is a Perfectly Sized Rocket, I made the case for why a ~5t fully reusable launch vehicle is the perfect vehicle to compete with existing medium-lift partially reusable launch vehicles. In short, they are already capable of launching most payloads at that class, with orbital refilling, they can launch most GEO satellites, and full reuse allows them to launch constellations at a reasonable cost.

Titan does not seem to get any of these advantages except for being able to launch all payloads under 5t, which is a majority of payloads. It has not been announced if they plan reusability for Titan, but if they plan to be competitive against other launch vehicles in 5-10 years’ time, reusability is a requirement. Furthermore, there exist extremely few Canadian satellites that could take advantage of this vehicle. To get the sufficiently low cost to launch constellations effectively they need very high cadence. If there remains a launch shortage in several years, they may get contracts from the US constellation companies, but the launch market will be even more competitive at that time.

Overall, 5t is a strange class for a maybe reusable medium lift launch vehicle. SpaceX cancelled the Falcon 5 - 4.2t payload capacity - for a reason. I don’t think it’s guaranteed this vehicle will be successful in 5-10 years given the lack of Canadian payloads that could take advantage of it and the increased MLV competition we’ll see then.

Conclusion

There Really Aren’t Many Canadian Payloads

The biggest issue with being a Canadian launch provider is that there aren’t very many Canadian satellites. Looking at the last few years, there is demand for launching ~10 Canadian satellites per year. This could increase many multiples in the future, but it remains a tiny market compared to the US or the rest of the world.

The majority of Canadian satellites are commercial observation or communication constellations. These companies have a profit incentive, and I expect them to choose the launch provider which is cheapest and fastest. Here, NordSpace would be competing against SpaceX Rideshare missions and Rocket Lab’s Electron, both of which are extremely hard to compete against on cost or schedule.

This leaves university payloads or government and military payloads. This is maybe 30-40% of the total lifetime history Canadian launch demand. I assume university launch demand is fairly inelastic and government/military payloads are at most 15% of Canadian launch demand. This is the best market for a sovereign Canadian launch company, and it’s a very small market.

5 payloads a year is not even enough to fill a single Tundra rideshare mission to Sun Synchronous Orbit (250 kg to SSO), which is not enough to support a commercial company.

Responding To More Founder Quotes

“We’re really treating Canada as a pathfinder market.”

As Goel mentions, competing for international payloads is an option for the company and a great path forward. However, this is a very competitive sector, and they may fall for the same issues Firefly and other 1-ton class rockets are having, not being the right size for most small satellites.

“By the end of the decade, we’re doing at least one launch a month. We think that’s a lot more reasonable than new companies coming out of the gate who say they’re going to launch 50 times a year.”

These optimistic predictions of launch rate must be under the assumption of either increased Canadian government/military launch demand or an expectation of success in the global commercial market. This will be extremely difficult, and I hope to see them succeed, but the launch business is not forgiving!

“This is not a multi-billion-dollar project,” he added. “We can do this for sub-$100 million easily.”

I’ll operate under the assumption that Goel is describing the cost of the Tundra program to get to a first launch, also not sure if this is CAD or USD. Hopefully I’ll have the opportunity to ask Goel for clarity myself! Either way, $100M USD in 2025 is optimistic for the first launch of a 500 kg class launch vehicle. Even more optimistic if this includes Taiga development costs.

There’s a slide from a NordSpace presentation in which they mention a 27.5 kg lunar orbit payload capability for Tundra (strange they mention lunar orbit and not TLI, are they planning direct insertion? Extremely cool if true.). The founder also talked about letting technical teams move without impedance from management and moving very fast. This is nice but, founders who talk about a fast pace of iteration are a dime a dozen. Hopefully these insights will really be implemented!

Conclusion

Overall, the advantage of a domestic launch company is launching domestic payloads. There aren’t many of these in Canada, so they’ll have to expand to the extremely competitive commercial market. The strategy of 50 kg -> 500 kg -> 5000 kg is sound, even if some of those payload mass classes don’t align perfectly with the market.

I am a Canadian, and I hope to see them succeed! However, like all launch companies, the odds are against them.