All Mistakes On UBC Solar Were Due To People

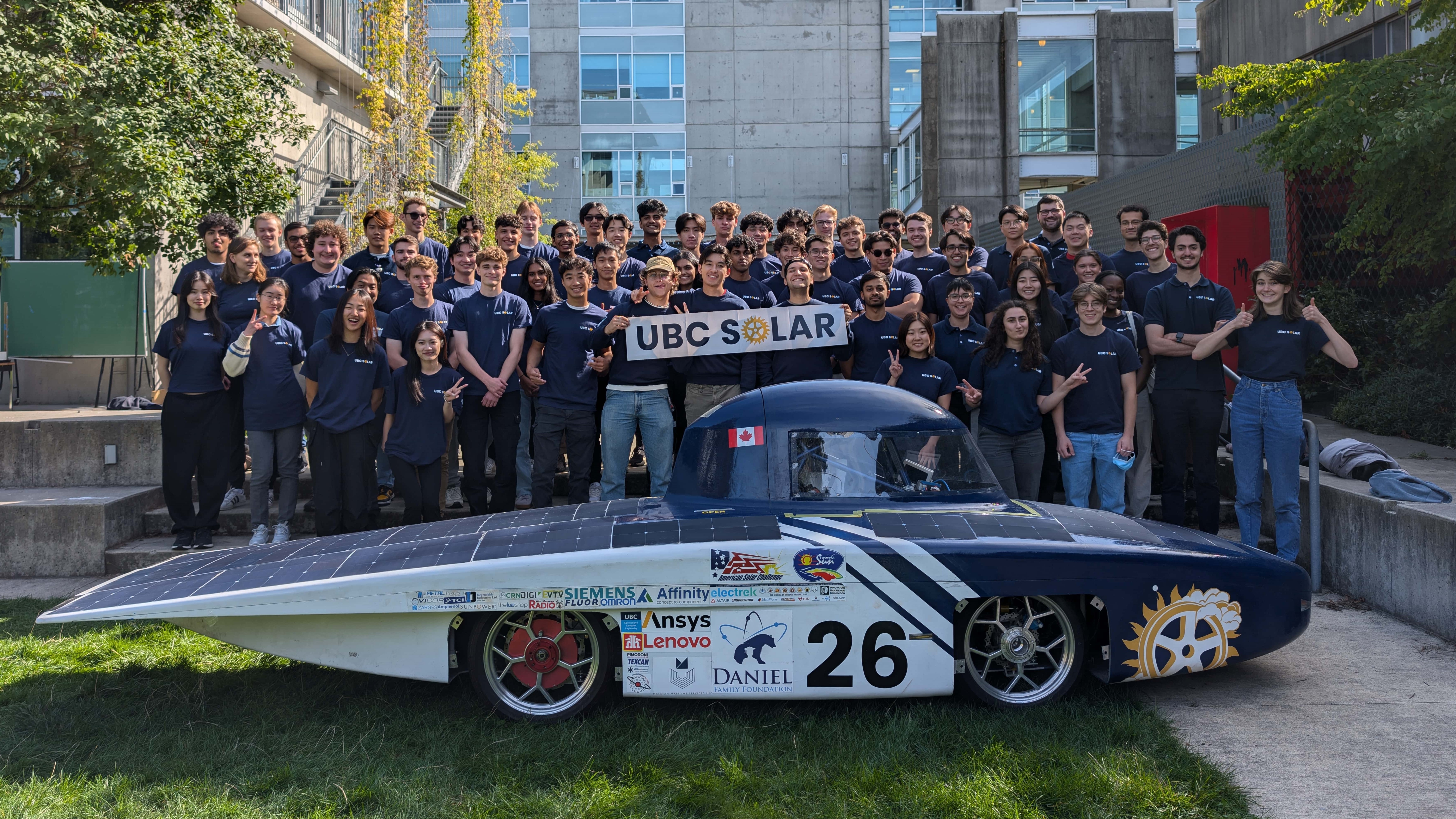

I started writing this only for myself as a reflection on my first year on UBC Solar (before we go to comp in a couple weeks!), but it has turned into a post that I think contains many useful actionable insights for anyone on a student design team or in a similar organization. I hope you find it useful!

Take away whatever you will about my interpersonal skills, but I think I have great intrapersonal skills!

All Mistakes On UBC Solar Were Due To People

All the mistakes I’ve seen made on UBC Solar were due to people. We obviously have no robots, but this is not a non-trivial statement. All mistakes are due to people, and you are a person. This means you can make mistakes or improve your ability to spot mistakes and not make them yourself. This is part of my motivation to write this post.

Technical mistakes are an easy example, especially on a student design team. This is usually down to improper understanding of the theory of operation of the system. This is solved by several more years of university and more experience and is not what I’ll primarily focus on.

Interpersonal mistakes and organizational/managerial mistakes are what pose a much greater concern. Even taking the example of a technical mistake that a first year student makes, this is down to a mistake of a team lead not properly assessing the member’s abilities, supporting them in the right way, or not providing the right framework / environment for the member to succeed.

The primary types of mistakes/issues I’ve seen are in no particular order:

- Not understanding the gravity of what you’re working on

- Not having the right instincts when posed with a problem

- Not setting up members for success with the right approach

- Not letting members work on what they want to

- Not being aware enough of learning opportunities or not seeking them out

- Not fundamentally understanding the importance of project updates, test plans, and Design Review documents

- Not giving enough honest feedback to each other

- Hiding incompetence behind fast decision making and not fully explaining yourself

- Not being precise in your speech and meaning what you say

Notice that 8/9 of these start with “Not”. These are unforced errors that you can correct!

1. Not Understanding The Gravity Of What You’re Working On

My first UBC Solar project was characterizing the main pack current sensor and this was a great first project for me. I was able to learn a ton about how our battery pack works and about firmware / electrical engineering in general. It was also low risk enough that I could do a characterization test with the sensor with a benchtop powersupply and not risk damaging the pack. I grew to feel confident in my ability to work with the battery.

However, when I was tasked with characterizing the low voltage system current sensor, I made the mistake of probing pins that were directly next to ground and 3.3V. It was almost inevitable that a slip of the multimeter probe would short the pins and kill the microcontroller on the ECU. This was a mistake that involved a lack of understanding of the system.

Furthermore, it was a mistake that could have so easily been spotted! “Hey Chris are you probing right next to those other pins? What are they? Are you sure you won’t short anything?” Anyone could (and should!) have asked this walking by, but no one did. Whenever anyone is working on a 134 V battery pack, you should be asking them questions about what they are doing and why for both your learning and to keep them focused and reevaluating the path they’re taking.

You’d think this would be enough warning to stave off anyone who doesn’t know what they’re doing!

We use the LTC6813 chip in our battery to sense the temperature and voltage of the battery modules. This same chip is used by Tesla and is complex enough that not a soul in the design team bay fundamentally understands how it works and is completely confident using it.

We’ve shorted the chip seven times (my lead gave me this number in the middle of a standup I was giving) in the past couple of months. None of us fundamentally understand how it works and make we guesses constantly. This is great for learning, but is terrible when an inexperienced member is working on the pack and doesn’t realize that one wrong choice and they fry another chip which costs on the order of $10 and several hours of design team member time to fix.

Some of the mistakes to due with this chip have been truly stupid and as a team (or our elec lead specifically) we haven’t taken a step back to fundamentally consider why we’ve made fried SEVEN of these chips now.

Idiot proofing the design works to a certain extent, but you should know what you’re doing!

Fun Anecdote:

Alex Ezzat was the previous battery lead, mechanical lead, electrical lead, then team captain on UBC Solar and now is a senior mechanical designer on the Tesla Semi. he did a talk on how to design a battery pack at the end of last summer internally for Solar (unlisted on Youtube go watch!). He talked about idiot proofing the design of your battery pack so that even new members with both hands in the pack can electrocute themselves or short the pack. Hey that’s me! I’m the that new member he’s trying to idiot proof against!

I talked to Alex when flew to SF a couple weeks ago. Very chill guy. You must understand that you have agency and can just cold email these people!

2. Not Having The Right Instincts When Posed With A Problem

I’ll start with an example:

Today one of the team leads on UBC Solar was trying to clear some wire harnesses out of the way to put the battery pack in the car. Another member - who was standing right next to him - had done some necessary rewiring for new boards and didn’t take into account clearance with the battery. Without knowing the member who did the work was right next to him, the team lead started loudly complaining about how stupid it was to put the wires where they were and that this was a terrible design.

We all probably know how it feels to do some work you think is good, then have someone come around and say it’s shit. This is doubly worse when they don’t know you did it and you think “Should I tell them it’s my work?”

The insight here is that when posed with a problem your first instinct should not be “Holy fuck this is a shitty design whoever did this ia stupid idiot.” This is bad because (1) the person might be next to you, (2) you are not properly setting yourself up to solve the problem as you’re just complaining and (3) this leads to emotionally trying to hammer out a solution and not taking a step back to reevaluate your approach (which might be wrong!).

UBC Solar’s former Battery Management System and then electrical lead, Mischa Johal, would never have made such a mistake! He understands that you must approach a problem from the right way and always reevaluate your approach. In my mind I can always hear the copious insights he shared in his blog post Reflecting On UBC Solar whenever someone makes a mistake that doesn’t align with what his approach would be.

Quick aside: When you want to become competent in a particular field and know (or know of) someone who is extremely competent in that particular field, fake it till you make it works! If you try to act like that person and constantly try to understand why they do the things they do, you will eventually become that person in that field.

You can’t quite generalize this to trying to literally be another person, but it works in specific domains. For example, on the first day on UBC Solar I identified that Mischa had a ton of technical knowledge I didn’t know and more important had implemented a ton of managerial practices that I’d never seen up close before. I instantly decided that I need to extract all the insights I can from him and try to emulate his approach to problems.

3. Not Setting Up Members For Success With The Right Approach

“I put 100% of my focus into applying frameworks that would empower members to output fast-paced, high quality work that required minimal oversight from leads, while at the same time training members to become leads themselves - following the team motto of “recruit your replacement”.”

Mischa Johal, former UBC Solar Electrical Lead

Your goal as a team lead on a student design team must be to set your members up for success and hence to recruit your replacement. This requires maximally competent and productive members which in turn requires as many learning opportunities as possible.

One easy example here is that if you’re a team lead and one of your members (or any team member) is standing around while you’re working on the car, you should be explaining everything you’re doing and why and taking/asking questions.

You’d be surprised how many times a team lead is working on the car and a member’s sole role is “tool holder.” What a waste of time! This is also exactly how to get a member to not want to come back to the team.

I was pretty much in this position for an hour today. I usually ask very many questions, but no one seemed to entertain them today from a combination of stress about the issue being solved and not caring to explain it.

Again, not caring to explain an issue is a great way to not force yourself to reevaluate your approach to a problem. Rubber duck debugging works!

4. Not Letting Members Work On What They Want To

This point is mostly just me complaining about something that happened today, so straight into an example:

Today we were working on the battery and I wanted to probe the isoSPI bus in our battery with an oscilloscope to directly see how bits were being sent (isoSPI sends bits as increasing or decreasing edges). We had around 10 minutes before we would put the battery pack in the car and I thought it’d be a great learning exercise for me and the team.

The response from the team leads around me was “No this isn’t critical to getting to comp and you have other things to do just do the tasks on the list we wrote for you.”

What a demotivating response! I understand that we must get the car ready for comp and the test you were getting ready for was on the critical path, but what a wasted learning exercise and what an incorrect response to a curious member! At the very least, “Very good idea for a test Chris, but I want to focus 100% on the test at hand right now.” This gets back to point 2, not having the right instincts on what to say when posed with a problem.

5. Not Being Aware Enough Of Learning Opportunities Or Not Seeking Them Out

This is a combination of two stories so far, the test I wanted to do with isoSPI and my main pack current sensor characterization.

The entirety of my first UBC Solar project was a learning exercise because I was learning the theory of operation of the battery pack to the point where I could make a useful contribution in characterizing the main pack current sensor. This project took ~5 months to complete and after it was done the old electrical lead, Mischa, came it and among many other insights made the point that we shouldn’t be completely disappointed about the path this project took because so many of the tangents taught us so much.

If we were aware from the start that this project was really about getting me up to speed on the battery pack and how it works, we would have had a different approach that would have been more useful.

The goal of a student design team is twofold: (1) to succeed at competition / build something that works and (2) to turn engineering students into competent engineers.

We should always be aware of the second goal and look for how certain projects can be used to teach members about complex systems, how they work, and how you can improve them. This also helps to serve our first goal in that we have more competent members who can contribute to the project.

6. Not Fundamentally Understanding The Importance Of Project Updates, Test Plans, And Design Review Documents

When I started my first Solar project, my team lead didn’t push too hard for me to write project updates and design review documents (Solar has a standardized process/template for these). I didn’t understand the importance of it and saw a template and thought this was stupid busy work.

Only much later reading Mischa’s blog did I understand the importance of these documents. They are not just busy work, they are ways to ensure your project is on the right track and that you are thinking about the right things (eg. What exactly are our requirements? Is this feature on the critical path? What approaches/alternatives have we not considered?).

Project updates and test plans also serve as great documentation for yourself and future members. Furthermore, they force you to reflect on what you did. This is also why project blog posts are so important!

Recently I saw another phenomenon of team leads pushing for project updates and design review documents, but not fundamentally understanding the importance of them. This is essentially cargo cult science. You’re following a process laid out by your predecessors but without the knowledge of why it was put into place. This diminishes your ability to critically think about the process and how it can be improved.

7. Not Giving Enough Honest Feedback To Each Other

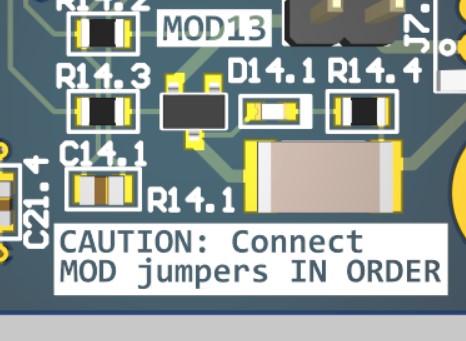

A precursor to my current sensor testing setup.

The most useful feedback I’ve ever gotten on UBC Solar was from my team lead, Krish, during my main pack current sensor characterization project. I was setting up a benchtop test which involved measuring the current going through the current sensor with a digital multimeter (DMM). I had set up a lot of other wires to measure voltage and when it came to measure current, I tried to set up the ammeter in parallel with the current sensor.

Krish quickly pointed out my mistake and later was giving me feedback and said that while I am good at firmware, I sometimes have bad hardware intuition. Since then I’ve made it a point to read more electrical engineering textbooks and improve my hardware intuition. This was extremely useful feedback and shaped how I used hundreds of my hours in the past few months.

Side note:

a positive statement then your negative feedback is a great way to give feedback! Peter Beck’s response to a blog post of mine consisted of “Very well written article” and then a full paragraph of what I should have added. Perfect! Makes me feel good and tells me what I can improve on.

It’s a problem that this piece of feedback I got ~5 months ago and there’s been nothing since. Given how important this feedback was to me (and the allocate of hundreds of my hours and the projects I choose to take on), we need to be giving honest feedback to each other like this more often!

8. Hiding Incompetence Behind Fast Decision Making And Not Fully Explaining Yourself

Grok came up with this one: The Competence Illusion. When you try to hide your incompetence behind fast decision making and not fully explaining yourself.

I’ve seen a few leads do this on UBC Solar. They make a decision or give an explanation to a question very quickly and try to brush it off as quickly as possible and as “obviously correct 100%.”

This is lying to yourself and others about your ability, but worse yet it’s closing the door to learning opportunities! When you don’t know enough to make a proper decision or give a proper explanation to a question, it’s often the right approach to consider what information you don’t have and seek it out.

A great way to spot when someone is hiding their incompetence is to ask “Why?” several times. You need to be slightly careful to not just say the word “Why?” over and over again like a child - you do actually have to formulate questions. However, if you ask probing questions long enough, you’ll get someone to the position where they’re unable to answer. Maybe they respond aggressively, or maybe they take it as a learning opportunity and realize there’s a hole in their knowledge. Sometimes we do just not realize that we don’t know something and this is a great way to find out.

9. Not Being Precise In Your Speech And Meaning What You Say

“When a company is meandering, it’s management staff is demoralized. When the management staff is demoralized, nothing works. Everybody feels paralyzed. This is exactly when you need a strong leader setting direction. It may not be the best direction, just a strong, clear one.”

Andy Grove, Only The Paranoid Survive, Chapter 8

This point is something that generally annoys me when I hear it and it’s a broader principle that applies to life. It’s also rule 10 in 12 Rules For Life.

Many times I’ve seen team leads say things off hand or even make specific points as answers to questions that they don’t actually mean. When I see someone say one thing one day, act a different way, then say another thing the next day, I have no idea how to respond as a design team member.

This leads to many uncertainties around the team. What is your vision for how this project is going to go, do you even have a vision? How do you want me to act as a design team member? What should our priorities be to get to comp?

This leads to the inconsistent thoughts and behaviour of a team lead transferring onto the team members themselves. This is how you get demotivated members and a disjointed unaligned team.

Like I’ve said before, a great way to combat this is to constantly ask questions and seek clarification. If you don’t understand something anyone says, ask them to clarify. If they brush you off, ask again. Continue asking until things become obvious, even if that thing is that the person you’re talking to doesn’t know what they’re talking about. Generally though, especially on a student design team as great as UBC Solar, people are happy to explain things and clarify and to learn new things when they reach the ends of their knowledge!